Project Description

One of the more intriguing lost chapters in modern architectural

history is the period of time that 1962 Yale School of Architecture

graduate Norman Foster, Hon. FAIA, spent studying with Paul Rudolph.

Other than the 1963 Creek Vean House—a

semi-subterranean concrete-block fugue designed with fellow Yalie

Richard Rogers, Hon. FAIA, for the latter’s then-in-laws—it’s hard to

see much of the Brutalist master’s heavy hand and gorgeous gloom in

Foster’s subsequent output of determinedly lightweight and relentlessly

sunlit glass-and-steel buildings.

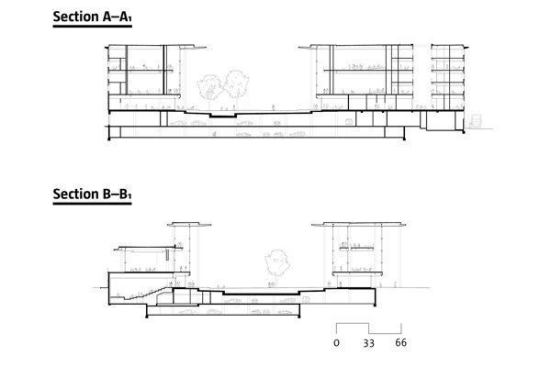

The latest in this succession is, fittingly, back in New Haven, Conn.:

Edward P. Evans Hall, the new home of the Yale School of Management,

which opened in January. At 249,743 square feet and a reported $189

million, the building assembles the school’s formerly scattered

facilities, which serve some 300 students, around a grassy little

courtyard and under one deeply overhanging roof. Monumentally shiny and

not especially subtle, the building is closer in geography and spirit to

the nearby Eero Saarinen and Philip Johnson buildings on Yale’s

peripheral science and athletic campuses than it is to the dense Rudolph

and Louis Kahn masterpieces at the university’s heart.

Foster’s recent work generally divides itself between the latently

classical and the retro-futuristically biomorphic. Evans Hall tends

toward the former, with—somewhat in the manner of the architect’s 1993 Carré d’Art at Nîmes,

France—a row of 15 tall and slender columns (some 60 feet high on

25-foot centers) along its entrance façade. Set back behind that

colonnade, under a pale canopy, is a deeply modulated glass curtainwall.

The modulations are informed by Foster’s signature half-circle stair

landings and a boxy reading room, as well as the perimeter expressions

of interior elliptical volumes that add a touch of the biomorphic to the

plan. On the ground floor, these drum-like elements house a coffee shop

and commons. On two double-height upper levels, they enclose 16

generously scaled classrooms. Their deep blue cladding, visible through

the glass façade, is vanishingly close to the signature Pantone 289 of

Yale’s heraldry. Aligned with the main entrance across the courtyard is a

semi-elliptical 350-seat auditorium and event space.

The ovoid geometry propagates toward the central courtyard’s glazed

walls, which wiggle in and out along the north and south sides. This

curvaceousness ensures some sparkle in varied daylight, directs the

drift and flow of students and faculty through the adjacent circulation

space—and presumably encourages the serendipitous encounters and

spontaneous gatherings on which good management relies in this era of

wearable technology and flat organizational charts.

Today’s corporate and academic campuses favor breakout spaces—nooks,

perches, lounges, cafés—as architectural expressions of the

reconfigurable formlessness characteristic of adaptive and

technologically driven organizations. In Foster’s well-populated

renderings of Evans Hall, each area between the elliptical classrooms

and curved glazing features lively gatherings on banana-shaped

furnishings—evoking something between a conversation pit and an airport

gate. These once-secondary areas, nominally circulation space, may come

to accommodate the primary functions of both the building and the

organization it houses—a confluence of current best practices in

architecture and management and a stimulating inversion of Kahn’s

canonical division of buildings into served and servant spaces. However,

the willful North–South symmetry of Foster’s plans—a tidy classicism

not abundantly evident in the collegiate gothic of the surrounding

campus—doesn’t allow for a fuller realization of this transformation.

During Foster’s time at Yale, while Rudolph’s Art and Architecture

building was still underway, architecture studios were accommodated on

the top floor of Kahn’s Yale University Art Gallery. Although that

building is primarily known for its famous blank brick wall along Chapel

Street, it is also Kahn’s glassiest work, with largely unbroken

curtainwalls along its north and east façades. Some memory of those

promisingly open edges beneath a broad sheltering roof must have

animated Foster’s design for Evans Hall. Perhaps over this new

building’s life, as in any architecture studio, the lively asymmetries

and messes missing in the plan will be provided by the students

themselves. (And, for MBAs in the long shadow of the Great Recession, a

dash of necessary Rudolphian gloom, too.) —Thomas DeMonchaux