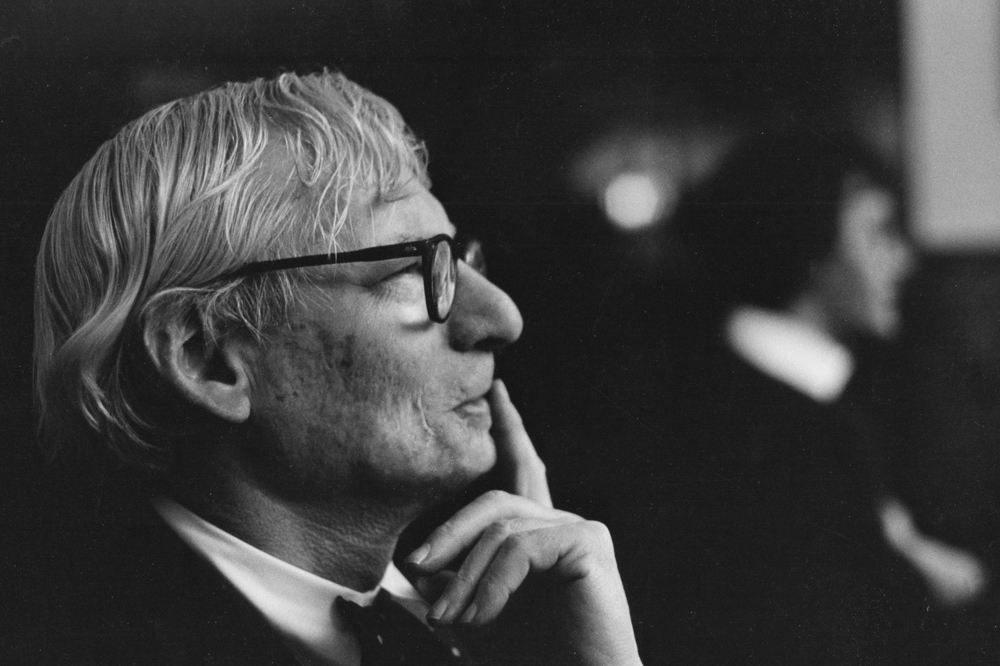

“What do you think of Louis Kahn?” one of my students asked last week. “Oh, well, I think he was God,” I answered only half-jokingly and turning away to my next task. “Oh,” she said. “Well, but he was sort of a creep, wasn’t he?” I turned around, faced her, and didn’t know what to say. For years, we have thought of Kahn as the misunderstood mystic who died alone and unidentified in his rumpled suit in a Pennsylvania Station restroom but had somehow managed to design some of the most beautiful and evocative monuments of the 20th century. Only after his death did it begin to emerge to the public that he was a serial philanderer who found his peculiar charms and status to be effective with many women, and who fathered several children out of wedlock. With the release of Nathaniel Kahn’s My Architect in 2003, the general public knows him as much for this rapacious behavior towards women as they do for the few masterpieces he produced during his career.

The encounter made me wonder what we will think of some of the living male architects who now bestride the architecture world (limited though it be in its ambit) as colossuses. Several of them have had affairs with students and former students, a few married them, and many more were known to make advances on women every chance they got. One in particular was rumored to enjoy exposing himself to female employees, with no apparent consequence.

“Well, but he was sort of a creep, wasn’t he?” I turned around, faced her, and didn’t know what to say.

Margaret Crawford, a UC Berkeley professor of architecture history, recently posted on Facebook that her thesis adviser there has had a long history of harassment. Many women are speaking out now about the recent and public revelations of shenanigans that have happened in Hollywood and Washington, D.C.; Westminster Abbey; and essentially worldwide. How soon until some women start coming forward to describe what they had to go through as they were making their careers in architecture? And when that happens, will it alter how we see the perpetrators’ work?

I don’t know the answer to the first question, and the answer to the second question is difficult. In an ideal world, we should be able to separate the work from the man or woman who made it, but in the real world, the cult of the “genius maker” so thoroughly defines the way in which any art is made and received that we cannot ignore questions of character when we look. Moreover, the inexcusable behavior of men has too long let them build unabashedly while inhibiting the work and the careers of women.

Too many male architects see the world as a supine figure waiting for their brilliant erection to bring it to life.

On another level, as I tried to point out more than 20 years ago in my book Building Sex (William Morrow & Co., 1995), the values of the architecture world are thoroughly bound with notions of masculinity. The glorification of the big, the muscular, and the tall, the suppression of comfort and sensuality as important values, and the complete domination of the architecture world (still!) by men are all wrapped up together. Too many male architects see the world as a supine figure waiting for their brilliant erection to bring it to life.

On a more practical level, the lack of everything from role models to career paths that take into account women’s needs in areas such as offering flexibility in caregiving, all in addition to this deep-seated male bias, continue to make it very difficult for women to succeed in the profession. While women make up nearly half of architecture graduates, the percentage of women in the profession decreases over time. Part of that difficulty is the perpetuation, until at least very recently (and perhaps still ongoing), of a culture in which male architects and professors thought they could have their way with female students and colleagues.

Part of that difficulty is … a culture in which male architects and professors thought they could have their way with female students and colleagues.

So do I look at Louis Kahn’s architecture differently now? Do I see the work differently than I did when I first visited the Salk Institute and the Exeter Library, or when I worked as a guard at the British Art Center just so I could be inside that building all day? I would like to say that I do, but my male biases are so firmly in place, and so much of what I love about architecture is bound up with Kahn’s work, that I cannot help but love his designs. Still. I would like to think these feelings are because I can rationally explain the work’s merits beyond its designer’s demerits, but I am not so sure. Perhaps I am not as woke as I would like to be, but rather still asleep in the prison or the “Room” Louis Kahn erected to justify his own creation and from which I see the world of architecture.

I hope that women do come forward to tell their tales, and their stories don’t get lost in the sensational news cycle or get ignored by their colleagues and firm leadership, but instead lead to a serious debate on the values and standards of architecture as an art and a profession. They deserve to be heard.

Correction: We initially stated that Louis Kahn died in Grand Central Station. It was Pennsylvania Station. We regret the error.