Courtesy Toyo Ito & Associates Architects

Toyo Ito, Hon. FAIA.

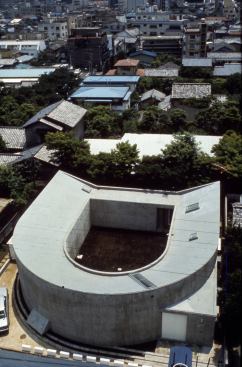

Courtesy Toyo Ito & Associates Architects / Photo by Koji Taki

White U (house), Nakano-ku, Tokyo, Japan, 1976.

Courtesy Toyo Ito & Associates Architects / Photo by Tomio Ohashi

Silver Hut (house) Nakano-ku, Tokyo, Japan, 1984.

Courtesy Toyo Ito & Associates Architects / Photo by Tomio Ohashi

Tower of Winds, Yokohama-shi, Kanagawa, Japan, 1986.

Courtesy Toyo Ito & Associates Architects / Photo by Tomio Ohashi

Yatsushiro Municipal Museum, Yatsushiro-shi, Kumamoto, Japan, 19… Yatsushiro Municipal Museum, Yatsushiro-shi, Kumamoto, Japan, 1991.

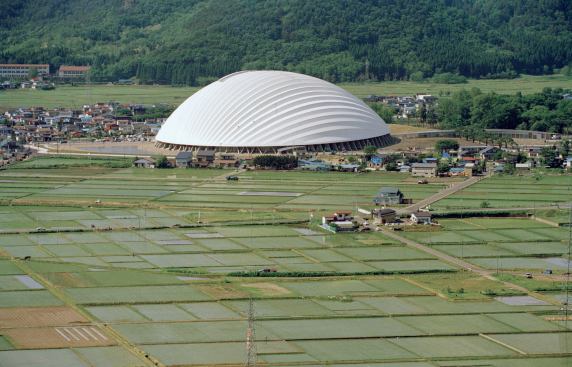

Courtesy Toyo Ito & Associates Architects / Photo by Mikio Kamaya

Dome in Odate, Odate-shi, Akita, Japan, 1997.

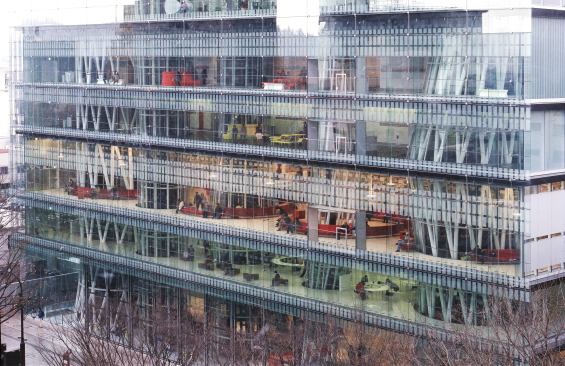

Courtesy Toyo Ito & Associates Architects / Photo by Nacasa and Partners

Sendai Mediatheque, Sendai-shi, Miyagi, Japan, 2000.

Courtesy Toyo Ito & Associates Architects / Photo by Tomio Ohashi

Sendai Mediatheque, Sendai-shi, Miyagi, Japan, 2000.

Courtesy Toyo Ito & Associates Architects

2002 Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, London.

Courtesy Toyo Ito & Associates Architects

2002 Serpentine Gallery Pavilion, London.

Courtesy Toyo Ito & Associates Architects / Photo by Hiroshi Ueda

Matsumoto Peforming Arts Center, Matsumoto-shi, Nagano, Japan, 2… Matsumoto Peforming Arts Center, Matsumoto-shi, Nagano, Japan, 2004.

Courtesy Toyo Ito & Associates Architects / Photo by Nacasa and Partners

Tod’s Omotesando Building, Shibuya, Tokyo, 2004.

Courtesy Deane Madsen

Tod’s Omotesando Building, Shibuya, Tokyo.

Courtesy Toyo Ito & Associates Architects

Meiso no Mori Municipal Funeral Hall, Kakamigahara-shi, Gifu, Ja… Meiso no Mori Municipal Funeral Hall, Kakamigahara-shi, Gifu, Japan, 2006.

Courtesy Toyo Ito & Associates Architects

Meiso no Mori Municipal Funeral Hall, Kakamigahara-shi, Gifu, Ja… Meiso no Mori Municipal Funeral Hall, Kakamigahara-shi, Gifu, Japan, 2006.

Courtesy Toyo Ito & Associates Architects / Photo by Tomio Ohashi

Tama Art University Library, Hachioji-shi, Tokyo, Japan, 2007.

Courtesy Toyo Ito & Associates Architects / Photo by Tomio Ohashi

Tama Art University Library, Hachioji-shi, Tokyo, Japan, 2007.

Courtesy Toyo Ito & Associates Architects

Za-Koenji Public Theatre, Suginami-ku, Tokyo, Japan, 2008.

Courtesy Toyo Ito & Associates Architects

Za-Koenji Public Theatre, Suginami-ku, Tokyo, Japan, 2008.

Courtesy Toyo Ito & Associates Architects / Photo by Fu Tsu Construction Co.

Main Stadium for The World Games 2009, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 2009.

Courtesy Toyo Ito & Associates Architects / Photo by Fu Tsu Construction Co.

Main Stadium for The World Games 2009, Kaohsiung, Taiwan, 2009.

Courtesy Toyo Ito & Associates Architects / Rendering by kuramochi+oguma

Taichung Metropolitan Opera House, Taichung, Taiwan (in progress… Taichung Metropolitan Opera House, Taichung, Taiwan (in progress).

Taichung Metropolitan Opera House, Taichung, Taiwan (in progress… Taichung Metropolitan Opera House, Taichung, Taiwan (in progress).

Courtesy Toyo Ito & Associates Architects / Photo by Daici Ano

Toyo Ito Museum of Architecture, Steel Hut, Imabari-shi, Ehime, … Toyo Ito Museum of Architecture, Steel Hut, Imabari-shi, Ehime, Japan, 2011.

Courtesy Toyo Ito & Associates Architects / Photo by Daici Ano

Toyo Ito Museum of Architecture, Steel Hut, Imabari-shi, Ehime, … Toyo Ito Museum of Architecture, Steel Hut, Imabari-shi, Ehime, Japan, 2011.

Courtesy Toyo Ito & Associates Architects / Photo by Daici Ano

Toyo Ito Museum of Architecture, Silver Hut, Imabari-shi, Ehime,… Toyo Ito Museum of Architecture, Silver Hut, Imabari-shi, Ehime, Japan, 2011.

Courtesy Toyo Ito & Associates Architects / Photo by Yoshiaki Tsutsui

Toyo Ito, Hon. FAIA.