Mitchell Kearney/Liquid Design

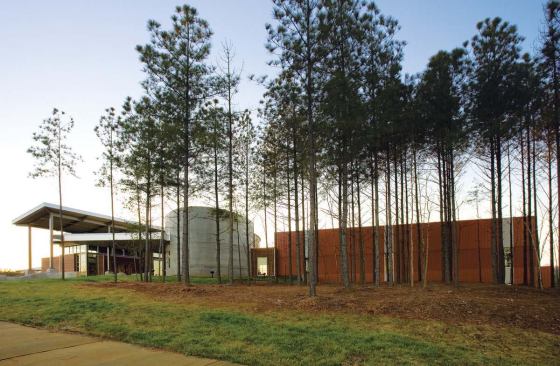

The centerpiece of the 316-acre USNWC complex is the River Cente…

“Design a mall and everyone has an expectation of what a mall looks like,” he says. “No one knows what an outdoor lifestyle park looks like, so this gave us a chance to really design—and go rafting for work.”

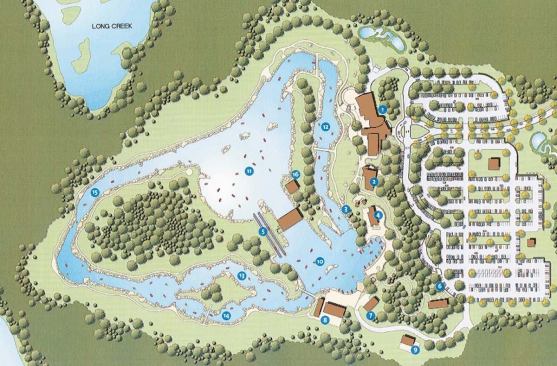

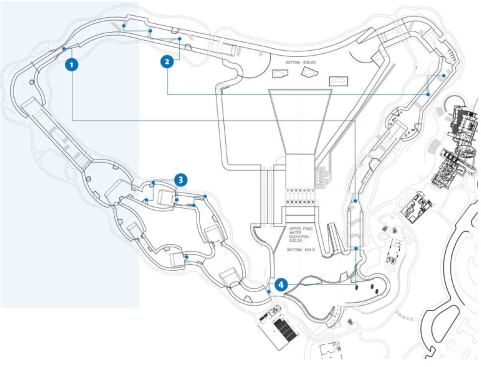

But the real novelties came with designing a river. To make a recirculating current, the team created an upper pond and a lower pond, divided by a dam and a phalanx of seven, 12,500-pound submersible pumps that cities might use to move stormwater. The pumps, which cost $1.6 million for the set, can fill an Olympic-size swimming pool in 71 seconds. Senior project manager Scott Carr of Rodgers Builders, based in Charlotte, got to work moving 350,000 cubic yards of dirt and pouring 1,400 truckloads of concrete using special forms he invented to pour perfectly sloped channels that flow between the ponds. Filtration systems from Israel and a UV-purification rig can disinfect the entire park’s water volume in a day, which pleased the code enforcers, who weren’t sure how to handle a project with virtually no precedents.

“It brought up a lot of interesting questions,” says Jeffrey Gustin, a former principal at Liquid Design who has since quit to work full-time on a massive adventure park in Mesa, Ariz., called Waveyard. “We’re creating a man-made, risky environment. Is it a pool? Do we need a fence? It was definitely an ongoing process.”

While Gustin worked with code regulators (not a pool; no fence), Shipley used computer software and models to predict “with uncanny precision” how to form rapids once the channels were filled with water. Fake rivers behave differently than real ones. The smooth concrete bottom allows water to move much more quickly than it might in a river choked with rocks and branches, so Shipley had to be careful that the rapids didn’t get too wild. He used rocks grouted into place to form obstructions, which create rapids, and invented special gates to fine-tune the flow. He also added drops that mimic those on real rivers, like the Chattooga, which forms the state line between Georgia and South Carolina. Thanks to Shipley’s calculations, some rapids at the park turned out easy—like the class II Entrance Exam—and others more difficult, such as the class III M Wave, which took some skin off Williams’ knuckles when he tried to paddle it and wrecked.

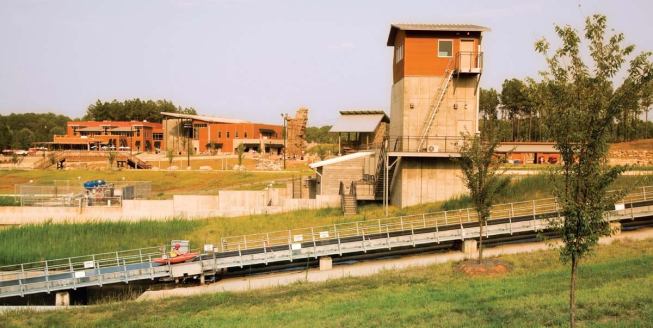

Maybe the coolest part of all: When paddlers reach the lower pond, a conveyor belt carries the raft 180 linear feet and 21 vertical feet to the upper pond and the start of the runs. There’s no need to get out of the boat. “People always ask how long it takes to make a run,” Williams says. “It’s like shopping. Sometimes you go in and out. Other times you hang out. I can tell you this: We took out most of the flat water to make nearly nonstop rapids. After 90 minutes, you’re worked.”

Well before the center opened, it caught the attention of the U.S. national canoe and kayak team, which had independently relocated its headquarters from upstate New York to Charlotte. The nonprofit paddling organization got behind the idea and now leases the land occupied by the park. Already, top-tier athletes like 2004 Olympian Brett Heyl use it for training. Other Olympic hopefuls like Butter—whose real name is Eric Hurd—moved to Charlotte specifically to work at the center. “We now have the biggest and the best facility,” says David Yarborough, executive director of USA Canoe/Kayak. “It’s a huge competitive advantage.”

But it’s the everyday visitors—a lawyer looking for a workout, bored teens casting around for something cool to do—that the center really aims to attract. It has to. Wise has two large loans to repay and needs the center to make money. To do that, he wanted a facility that catered largely to rafters, a forgiving and social way to play in whitewater. Sixty rafts, each with a guide and six paddlers who pay $33 a pop for a 90-minute session, could help turn a profit. Kayakers can pay $25 for the whole day.

“Compared to the overall river experience, it’s not a substitute,” says Kyle Irby, a 22-year-old college student and tireless kayaker who’s taking classes in Charlotte for the summer. The river he normally paddles, the Watauga, near Boone, N.C., hadn’t had water for months as the dry summer set in. “It’s kind of like skiing in North Carolina. You can get bored once you do everything. It’s still really nice to be able to come here and practice.” Irby sets off to make a few more runs before cracking the organic chemistry books.

“A lot of people know about this place, but I don’t think they know how fabulous it is,” says Cindy Irby, Kyle’s mom, who sits on the concrete shore watching her son fly off drops and bounce through the rapids like a toy. “I’m not a kayaker,” she adds, “but doesn’t that look like fun?”

Tim Neville frequently writes for Outside, National Geographic Adventure, and The New York Times. He lives in Bend, Ore.

PROJECT U.S. National Whitewater Center, Charlotte, N.C.

CLIENT Jeff Wise, Executive Director, U.S. National Whitewater Center

DESIGN PROJECT MANAGEMENT Liquid Design

ARCHITECT OF RECORD Michael Williams, Liquid Design

LANDSCAPE ARCHITECTURE AND CIVIL ENGINEERING ColeJenest & Stone

WHITEWATER DESIGNER Scott Shipley, S20 Design/REP Building

STRUCTURAL ENGINEER Moore Linder Building

PME Jordan Skala Engineers

PUMP STRUCTURE ENGINEERING AND INSTRUMENTATION ENGINEERING Perigon Engineering

GENERAL CONTRACTOR RodgersDooley

CONSTRUCTION MANAGEMENT Scott Carr, RodgersDooley

COST $37 million