Jason Fulford

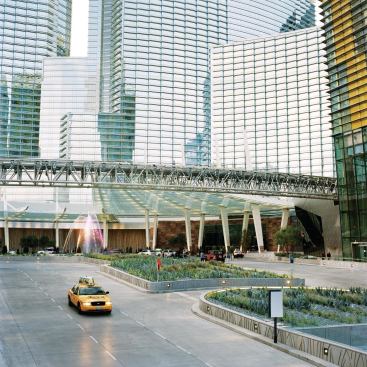

Libeskind's Crystals mall

A further indignity: The interior build-out was delayed as part of a cost-postponement strategy. Now, because there’s no one to look out the windows, much of the exterior is covered with billboards for “Viva Elvis,” a show in Aria’s theater.

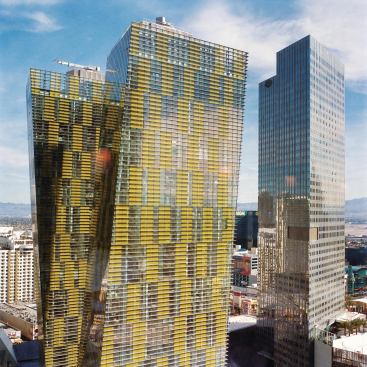

The beneficiary of Foster’s woes may have been Helmut Jahn, whose 37-story Veer Towers are now more visible from the Strip than they would have been had Foster’s building reached its intended height. What did Jahn, who like Foster can be a great innovator, make of the opportunity? His towers lean toward each other “like a pair of drunken tourists careening down a hotel corridor at the end of a very long night,” in the words of Los Angeles Times architecture critic Christopher Hawthorne. But the mustard-colored exteriors make the careening tourists seem a little queasy.

KPF and Viñoly designed the complex’s other “small hotels”—the 400-room Mandarin Oriental and the 1,500-room Vdara, respectively. Viñoly’s is the least appealing, a vast crescent of dark glass far back on the CityCenter site, reminiscent of the Wynn hotel at the other end of the Strip. KPF’s Mandarin Oriental, by contrast, approaches the Strip with a “plinth” that is comparable, in size and appearance, to a sleek new high school. The glass tower that rises from the platform is a beautiful envelope, but not much more than that. Ko Makabe, the chief designer for KPF, points to its well-proportioned entry courtyard, which is meant to give Mandarin guests a feeling of arriving someplace special, and its Asian-inspired curtain wall (made in China after U.S. bids came in too high). All of which are lovely, but none of which break new ground.

And yet the influence of KPF on CityCenter goes beyond the one hotel. The entire complex reminded me of Roppongi Hills, a mixed-use development in Tokyo designed largely by KPF. It turns out that, soon after CityCenter was proposed, Makabe and KPF principal Paul Katz led Baldwin, Smith, Van Assche, and others on a trip to the new complex. Impressed by what he saw, Baldwin invited KPF to compete for the plum Aria commission. Pelli prevailed in that bake-off, but KPF was brought back in when Mandarin Oriental chose a CityCenter location.

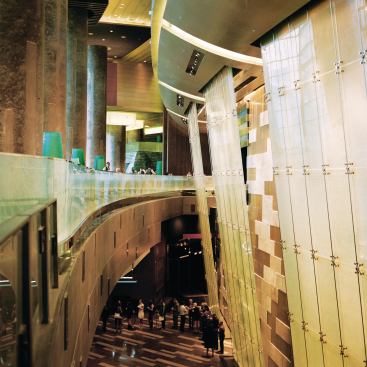

It is Cesar Pelli’s vast building, which curves around both of CityCenter’s traffic circles, that dominates the complex, both in size and quality. The Aria tower is extraordinarily graceful, thanks to metal louvers that break the vertical sweep and sawtooths that break up the horizontal arcs, without ever becoming busy. And the interiors are defined by the architecture. The hotel lobby, a towering space supported by huge, angled beams, is open and light, with exposed structure that ensures that Pelli’s work wasn’t hidden by an interior designer. In fact, Remedios Studios of Long Beach, Calif., filled the space with benches and dividers that recall, with just the right level of abstraction, the amenities of a city park.

At Aria, even the guest rooms respond directly to the architecture; the building’s hundreds of sawtooths mean that each room’s windows include a 90-degree turn. Since guests want to be able to black out sunlight, MGM struggled with the right drapery system, according to Van Assche, but resisted the temptation to value-engineer away the sawtooths. Meanwhile, the building’s gentle curves mean you never see the full length of those hallways, a blessing for visitors.

That its largest building is by far its most graceful is only one of CityCenter’s contradictions. Another is that it wants so badly to be urban, but turns out to be anything but. The site was master-planned by Ehrenkrantz, Eckstut and Kuhn Architects (EEK), the Manhattan firm known for designing New York’s Battery Park City 30 years ago. EEK design principal Peter David Cavaluzzi says his most important goal at CityCenter was to bring “buildings and activity right to the Strip, which to a large extent is very new for Las Vegas, where everything in the past had been pulled back.”

Admirable idea, but the size of the complex means that only a few of its buildings could have street frontage—the others are reached via traffic circles, which make some, but not enough, provision for pedestrians. A tram connects CityCenter with the Bellagio to the north and the Monte Carlo to the south; given its short range and lack of connections to the rest of Las Vegas, it can’t really be called public transportation. The complex would feel at home in Singapore or Dubai, but in a city like New York, a 67-acre interruption of the street grid would be considered utterly anti-urban.

“We tried to do things that are less about the automobile,” Cavaluzzi acknowledges, “but in Las Vegas, the force of the car asserts itself so profoundly. I think we came close.” In 20 or 30 years, he speculates, “maybe CityCenter can be retrofitted to respond to new types of transportation technology.”

Another contradiction is that the project is touted as a model of green design, but what it really shows is the limits of that designation. “The toilets are being used in Mexico right now,” says Murren, the chairman, explaining one of the building’s sustainable features: The contents of the Boardwalk Hotel, which previously occupied the site, were recycled whenever possible; that included sending bathroom fixtures south of the border. And he reels off a list of other green features, which together, he says, cost hundreds of millions of dollars—expenditures he “had to justify to the shareholders.” (The buildings have received a series of LEED Gold ratings.) It’s impressive for a CEO to know about—and even go to bat for—things like low-flow showerheads.

Yet it’s hard to imagine anything less green than 18 million square feet of air-conditioned space in the Mojave Desert. Admirable as some features of the complex may be, the only truly sustainable decision would have been not to build it.

Some days, the CEO himself leads tours of the complex, and he always makes a point of stopping in a small park, a tightly defined rectangle between the Aria lobby and Crystals. It’s no wonder that Murren—who wrote his senior thesis on vestpocket parks—admires this compact park with a classy Henry Moore sculpture as its centerpiece. Clearly, he knows that small can be beautiful, too.