Back in August, there was a classic New York City dust-up: dozens of scantily clad women with their breasts painted, generally in patriotic colors, were posing for photos with Times Square tourists in exchange for tips. “What happened was there’s five days in a row of naked ladies on the cover of The Daily News,” recalls Tim Tompkins, president of the Times Square Alliance, a nonprofit that is a tireless booster for the area. Whether or not this latest panhandling scheme—a bawdy offshoot of Times Square panhandlers dressed as Sesame Street’s Elmo or Sanrio’s Hello Kitty—merited its own media blitz is hard to say, but it was clearly making money for the tabloids.

Reports of the scandalous behavior of the desnudas, as the ladies are known, finally prompted the city’s police commissioner, William Bratton, to suggest getting rid of the pedestrian plazas where they were plying their trade. The city’s previous mayor, Michael Bloomberg, had installed the plazas in 2009, closing portions of Broadway to traffic. The New York Times quoted a radio interview with Bratton: “I’d prefer to just dig the whole damn thing up and put it back the way it was,” he said—a stance that seemed to get some support from Mayor Bill De Blasio.

“I’m, like, reeling right now,” is how Paul Steely White, executive director of Transportation Alternatives, an organization that advocates on behalf of bicyclists and pedestrians, responded to Bratton’s idea in a New York Times interview. Which is how most New Yorkers felt, or at least anyone remotely concerned with the importance of public space: outraged by the possibility that this wildly successful recasting of the most famous place in New York City—with upwards of 350,000 daily visitors and 39 million visitors a year—could be bulldozed because of a little nudity. “We thought that was crazy, and we said so,” Tompkins recalls. “And then every public space and transportation advocate in the city, if not the world, said, ‘This is crazy.’ ”

Giorgio Galeotti

Times Square visitors take in the scene from the red steps of the TKTS booth and Snøhetta’s granite benches

The irony of the desnudas controversy is two-fold. First, the reason that the police couldn’t somehow make the naked women go away is that Times Square isn’t a public place in the normal sense of the term. Broadway, pedestrianized or not, is still a street, not a park or a plaza, and streets, it seems, are a gray area, subject to “legal ambiguities,” according to the alliance.

The other twist is that much of Times Square as it existed prior to the late 1990s was, in fact, condemned and bulldozed to rid the area of all manner of vulgarity. A premier entertainment destination that, by the 1970s, was overrun with peep shows, porn theaters, massage parlors, and other disreputable enterprises, Times Square was reconceived, tabula rasa, as just another midtown office district with a few nice venues on 42nd Street for, say, Shakespeare.

1 Times Square when it opened in 1908

Schemes for remaking the area had existed since at least the John Lindsay administration in the 1960s, but the project didn’t gain traction until the early 1980s when developer George Klein got the nod from the New York State Urban Development Corp. to build a quartet of new office towers at the intersection of Seventh Avenue, Broadway, and 42nd Street.

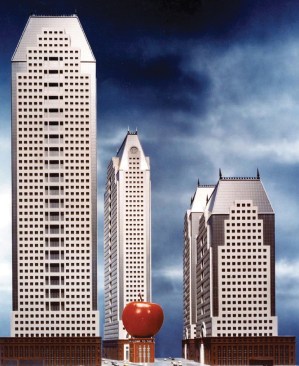

A rendering by Philip Johnson and John Burgee, FAIA, for a cluster of four sober-looking, limestone-clad office towers—not a hint of signage—topped with mansard roofs and fussy little iron finials, was released in December 1983. The plan also called for the demolition of 1 Times Square, the tower that opened—with fireworks—as The New York Times headquarters on New Year’s Eve in 1904, establishing the annual holiday tradition. In addition, the block of 42nd Street between Seventh and Eighth Avenues was to be largely cleared of its old theaters and remade into a glittering stretch of wholesome amusements leading to a gigantic merchandise mart at the west end. Critics largely hated the plan, which was widely regarded at the time as the death of Times Square. As the late Marshall Berman, a political theorist and observer of urban life, framed it, the four Johnson towers had been part of “an immense, abortive plan to turn Times Square into ‘Rockefeller Center South.’ ”

A 1980s Times Square rendering by Johnson and Burgee (apple designed by Venturi, Scott Brown and Associates)

When the stock market crashed in 1987, it put the project on hold for decade. In the interim, a group of designers had an insight: The genetic makeup of Times Square could inform major commercial real estate developments. Rebecca Robertson, who’d worked for the city as a planner, took over the 42nd Street Development Authority, a subset of the state agency overseeing the entire project. Initially charged with studying the future uses of the theaters within the redevelopment district, she hired Robert A.M. Stern, FAIA (then on the board of the Walt Disney Co.) to help. In in the early 1990s, Robertson and Stern began to hammer out an interim plan for retail and entertainment along what the team called The New 42nd Street. The project, which also involved graphic designer Tibor Kalman and his firm, M&Co, devised “42nd Street Now!” a strategy for codifying the honky-tonk aesthetic of the area.

The real beauty of the plan was its pragmatism. It called for placeholder businesses to keep the major development sites active until it was time to build. A brew pub (with a rooftop mock-up of a Concorde, a British Airways ad) opened on the plan’s Site 1, where a 50-story tower by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill was competed in 2002, and Disney opened a store in a one-story building where Kohn Pedersen Fox Associates’ 5 Times Square stands today. A couple of ornate historic theaters, like the New Amsterdam (leased by Disney) and the Victory, were preserved and restored. One, the 1912 Empire Theater, a one-time burlesque house, was moved 170 feet on steel rollers down a stretch of 42nd Street entirely devoid of buildings, to serve as the entryway to a soon-to-be-built 25-screen multiplex.

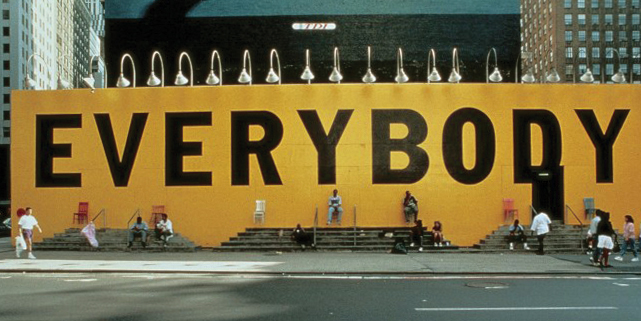

An art installation designed by Tibor Kalman and Scott Stowell in the early 1990s as part of the Times Square redevelopment project

Robert A.M. Stern Architects

Stern rendering for "42nd Street Now!"

By the time the economy was ready to support the construction of those four gigantic towers, there was a new rulebook issued by the Empire State Development Corp., a set of “design controls” that actually inscribed “the glitzy, bright lights environment of Times Square” into law. The rules set a minimum for the amount of signage on any façade facing Times Square, and towers were required to decorate the skyline with a “distinctive top.”

The first of the four towers, 4 Times Square, developed by the Durst Organization and designed by Fox & Fowle (now FxFowle), was completed in 1999. The building, which was fairly staid looking on its east side—the side facing away from Times Square—was otherwise smothered in signage. The other towers followed suit, spurring a video arms race. The new Edition Hotel, for example, designed by PBDW Architects and now under construction at the corner of 47th Street, promises to be wrapped in “one of the largest, uninterrupted outdoor LED media walls in the world.” The truth is that the glitz is now the economic engine of Times Square, generating hundreds of millions of dollars of annual advertising revenue for building owners, in some cases more than landlords net from leasing office space. The most extreme example is 1 Times Square. Empty but for a Walgreens on the ground floor, the tower takes in over $23 million a year in advertising revenue.

So Times Square—or a strategically amped up version of itself—was saved, but it was still not exactly a public place. There were no café tables under Cinzano umbrellas, no park benches, no fountains. But that began to change under Mayor Bloomberg.

Back in the bleakest moment of New York City’s modern history, the 1970s, there was one successful small-scale attempt at revitalizing Times Square: the TKTS booth, a trailer, supposedly temporary, dispensing half-priced Broadway tickets. In 1999, when the Van Alen Institute finally staged a competition to design a permanent booth, the winner was a bold scheme by an Australian firm, Choi Ropiha (now called Chrofi), that housed ticket sales in a box office situated beneath a set of bright red structural glass steps, south-facing bleachers where people could sit, relax, and take in the spectacle.

Rob Young

The red steps of the TKTS booth

It took the better part of a decade for glass technology to catch up with the concept, which was constructed under the supervision of New York–based Perkins Eastman. When the steps finally opened in 2008, they did something extraordinary; they provided a (somewhat) tranquil oasis in the midst of pure cacophony. I often take my grad students from the School of Visual Arts to analyze the dissonant scene. Sometimes I use 19th-century aesthete John Ruskin’s writings on “truth” in architecture to inspire the students to see what relevance his view of “honest architecture” circa 1849 might have in a place largely defined by the deceits of advertising. Other times I have them interpret the scene via Robert Venturi, FAIA’s ideas on “complexity and contradiction.” Either way, I ask them to really focus: to see the architecture behind the LED displays, the sky framed by signage above them, and meditate on the collective power of the jumbo images.

The opening of the red steps was followed by the Bloomberg administration’s decision to close Broadway in Times Square to traffic. Initially, the pedestrian plazas seemed like a prank, defined by paint on the pavement and furnished with beach chairs. Eventually, the beach chairs were replaced by café tables. And in 2010, in a move that was as political as it was urbanistic, Snøhetta was hired to make the plazas permanent. The grandest symbol of Bloomberg’s effort to redistribute the pavement would literally be cast in concrete.

Snøhetta

Snøhetta rendering of Times Square

Snøhetta

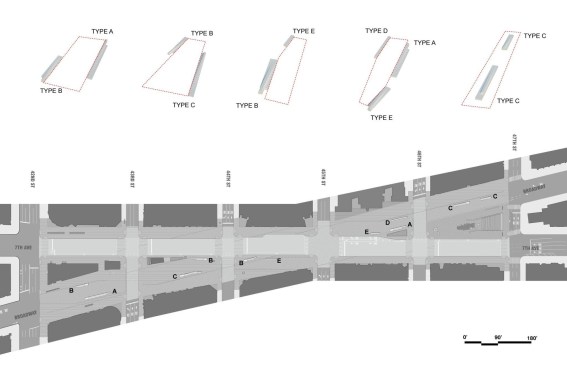

Snøhetta diagram for Times Square

Snøhetta, based in Oslo but well established in New York (it designed the National September 11 Memorial Museum Pavilion), realized that it was madness to try and compete with Times Square. Instead, the firm came up with a restrained arrangement of charcoal colored pre-cast concrete pavers, embedded with “nickel-sized steel discs that will capture the neon glow from the signs above and playfully scatter it across the paving surface.” Their design also involves a series of 10 minimalist granite benches variously configured for sitting, leaning, or reclining—the first one was installed in November (the project will be completed sometime next year)—plus things like conduits to supply power for outdoor performances in locations along Broadway’s path. The concept, according to Snøhetta, is “uncluttered pedestrian zones and a cohesive surface from building front to building front.”

The firm is doing something that seems almost as alien to Times Square as those Philip Johnson towers were; it is employing subtlety and refined taste. “When we think about public space we think a lot about generosity,” says Claire Fellman, a Snøhetta director and landscape architect. “Like how to make a space that feels welcoming, that invites people in to occupying a space in their own way.”

Bo Parker

The Marriott Marquis in the 1980s

When I huddle on the red steps with my students, I like to tell them the story of the Marriott Marquis Hotel, located between 45th and 46th Streets. Designed and developed by Atlanta-based architect John Portman, FAIA, it famously was a fortress of unadorned concrete when it opened in 1985. It turned its back on Times Square, aesthetically and literally. The lobby, for example, was sequestered on the eighth floor. The revolving restaurant and bar at the top of the hotel offers a wonderful panorama of New York’s spires, but absolutely no view of Times Square below. In an interview at the time of the hotel’s opening, New York Times architecture critic Paul Goldberger, Hon. AIA, asked Portman why it had no relationship with its surroundings. Portman replied: “Paul, there was nothing there to relate to. What am I going to relate to, Howard Johnson’s across the street?”

Sadly, the Howard Johnson’s Portman mentioned closed in 2005, the bizarrely endearing coffee shop replaced by an American Eagle store, but the native aesthetic of Times Square proved so powerful—and so lucrative—that it eventually overran Portman’s citadel with signage. Late last year, the hotel even got a new billboard, eight stories tall and spanning the entire block, using, according to the press release, “24 million pixels to create the most Ultra-High Definition display in the world.” And, now, for the very first time, glassy street level retail is being built along the Broadway side of the hotel (retail rents have quintupled in Times Square since 2009). Thirty years after its completion, Fortress Marriott is finally meeting the street. Call it the triumph of the glitz.

A rendering of the Marriott Marquis' new billboard

Meanwhile, the mayor has backed off from the threat to reopen Broadway to traffic in Times Square and has instead established a task force, led by Bratton and chairman of the City Planning Commission Carl Weisbrod, and including Tompkins and others, to hammer out enforcement issues. “We’re having this conversation about what kind of Times Square we do want,” Tompkins says. The task force has determined that if the pedestrianized zones of Broadway can become a real public place, they can lose their legal ambiguity and be easier to regulate. Beyond that, the Times Square Alliance has recommended dividing the area into different zones: “general civic” for cultural and political activities, “pedestrian traffic flow” for easy walking, and conspicuously small “designated activity” zones available to “fake Buddhist monks,” “costumed characters,” “desnudas,” and others. Hard to say whether this highly structured approach will work.

For years, there were dire predictions about what Times Square would become after all the new towers were erected and all the new themed restaurants and mega-multiplexes opened: boring, sanitized, Disneyfied. What I take from the desnudas scandal is this: Times Square is many things, but Disneyland is not one of them. The upshot of this story, the crazy, wonderful thing, is that it’s not the thoughtful urbanistic gestures—the red steps, the pedestrian plazas, Snøhetta’s carefully considered pavers and benches—that finally forced Times Square to be taken seriously as a public place; instead it was a roving band of nearly naked women.

Snøhetta

Snøhetta's pavers