It’s all about the drawing. I am talking about a specific drawing, the one that Frank Lloyd Wright did in 1888 when he was trying to get a job from the man he later came to call his “lieber meister,” or dear master, Louis Sullivan. Based on a house that McKim, Mead & White designed in Massachusetts, it is a pencil sketch of a façade. Wright outlined its roof and the edges of the walls, as well as the detailing around the door and windows, with sure and precise lines, while he indicated the masses with tones whose blurring and weight gives a sense of the design’s volumes. I have rarely seen an architect—let alone one who was 21 at the time—sketch with more assurance and clarity, evoking a design of great polish and beauty with such evocative economy.

©Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation

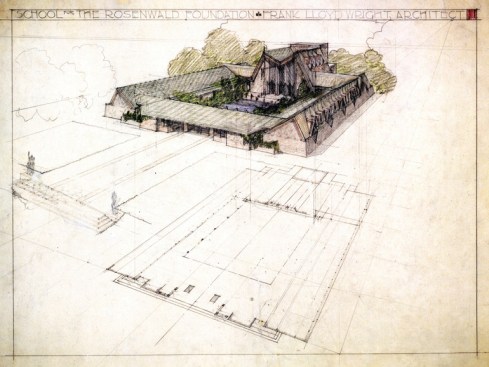

Frank Lloyd Wright's 1928 design for a Rosenwald School

The drawing introduces Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive, an exhibition that celebrates not only Wright’s 150th birthday, but also the Museum of Modern Art’s (where the show is on display) and the Avery Library at Columbia University’s joint acquisition of the Wright’s archive from the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation in 2012. It is, truth be told, the ultimate nerdfest for architecture lovers, although there are also some serious social messages to be found, like the unearthing and display of the “Rosenwald School” that Wright designed as part of a program to provide schooling for African-American children. But what the exhibition really shows is just one beautiful drawing after another, ranging from sketches to presentation drawings to working drawings.

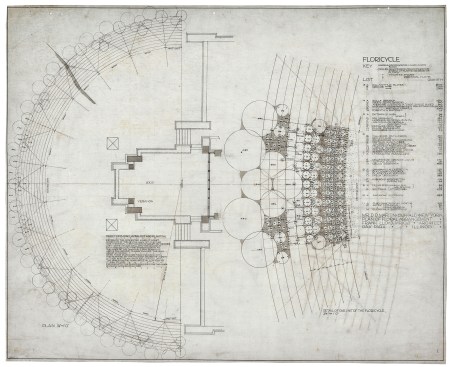

A different scholar curated each of the exhibition’s 12 sections, and each section keys off one particular image they found in the archives. Some of these exhibition triggers are projects that are less well known, such as the Rosenwald School, while others are a particular drawing of an otherwise well-known project, like the planting plan for the Darwin Martin House in Buffalo.

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library

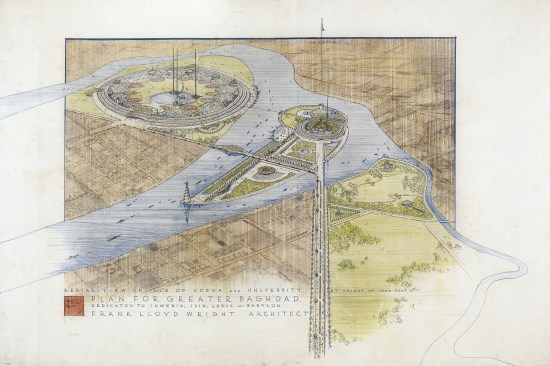

Frank Lloyd Wright (American, 1867–1959). Plan for Greater Baghdad, Baghdad. Project, 1957. Aerial perspective of the cultural center and University from the north. Ink, pencil, and colored pencil on tracing paper, 34 7/8 x 52″ (88.6 x 132.1 cm).

Whatever they depict, these images are artifacts that exhibit both Wright’s and his office’s design inventiveness, in everything from the detailing of a grille or a carpet, to the layout of a whole new city center for Pittsburgh or Baghdad. They show the machinery through which this eminently prolific architect sold and positioned, as well as plotted and planned, his projects. He and his collaborators, who ranged from Marion Mahony Griffin early on to Ling Po later in Wright’s career, were masters at showing proposed projects from angles that emphasized how the buildings grew out of the land and unfolded into constellations of crossing planes that both sheltered and opened the spaces inside. Wright could communicate all of that complexity with just one perspective. (One of the great tasks still awaiting true Wright nerds is figuring out who exactly worked on which drawing during the master’s seven decades of practice.)

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library

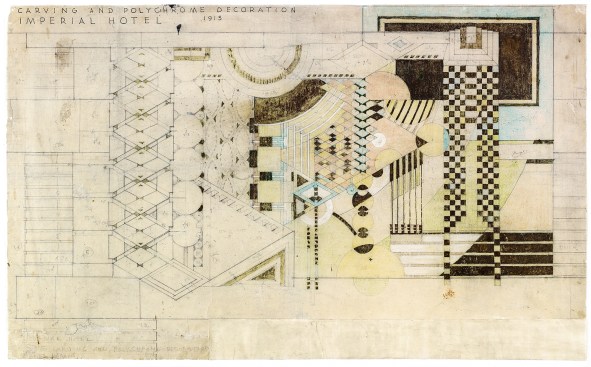

Wright's Imperial Hotel in Tokyo (1913–23)

Then there are the drawings that specify the details, from the endless search for new ways to elaborate such intersections with fanciful geometries and make surfaces, whether carpets or walls, into works of stylized floral art all by themselves. Wright was always looking to combine what he saw in nature with geometries that, over the years, became ever more complex. Some of the most powerful drawings are the working drawings for the Imperial Hotel in Tokyo: two ink collages that combine sections through cornices with details of frames and patterns that Wright trusted the craftspeople to conjure with stone, metal, and wood.

Each of these drawings is breathtaking—but then, I am one of those architecture nerds. The question is how they hold up as elements in an exhibition hosted by an institution that just a few steps away shows drawings and paintings by some of the greatest artists of the 20th century. The answer: Much better than I thought they would. Ultimately, however, I am not sure they have the depth and power of evocation that the likes of Matisse, Picasso, or Schiele were able to put in their sketches. Next to the exhibition hangs Oskar Schlemmer’s painting Bauhaus Stairway, which has regained its place over the landing in the newly restored staircase that was once MoMA’s main circulation path leading up to Guernica. To me, Schlemmer’s painting says more about architecture and what it means than most of what are, in the end, Frank Lloyd Wright’s illustrations.

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library

Frank Lloyd Wright (American, 1867–1959). Darwin Martin House, Buffalo, New York. 1903–06. Floricycle. Ink on drafting cloth, 32 1/8 × 39 3/4″ (81.6 × 101 cm).

Don’t get me wrong: I loved Unpacking the Archive and could spend many more hours there. The conundrum for me is the same realization I have had curating more than a hundred architecture exhibitions and have never been able to solve: Architecture in three dimensions, all around you, is the realization of what the drawing or the model only intimates. Wright was a good artist, but he was ultimately—and proudly—an architect.