Although building form and performance are often regarded separately, they have a profound connection. Some of the most compelling examples of architectural morphology are innovative ways to fulfill distinct performance objectives.

One example of this approach is 3XN’s Horten Headquarters in Copenhagen. This midrise office building, designed for a Danish law firm, is situated along the Hellerup waterfront on a site with ample solar exposure. The architect designed the facade to produce a series of staggered, faceted planes, adjusting the angle of the windows to face away from direct sunlight—thus reducing solar heat gain.

The insulated, travertine-faced composite panels take the full brunt of the sun, diminishing intrusive glare and reducing the building’s anticipated energy load by ten percent. As a programmatic bonus, the envelope’s zig-zag profile enables every employee to have a corner office.

The Horten building offers an inspiring counterpoint to the generic formulas of climate-attuned design. Architects are well-versed in the typical strategies of deep overhangs, light shelves, and horizontal windows oriented to the sun, which have become familiar signifiers of sustainability.

Yet such approaches are meant as a starting point, not a definitive practice. As 3XN demonstrates, fine-tuning a building envelope to its climate can—and should—be an opportunity for both formal and functional innovation.

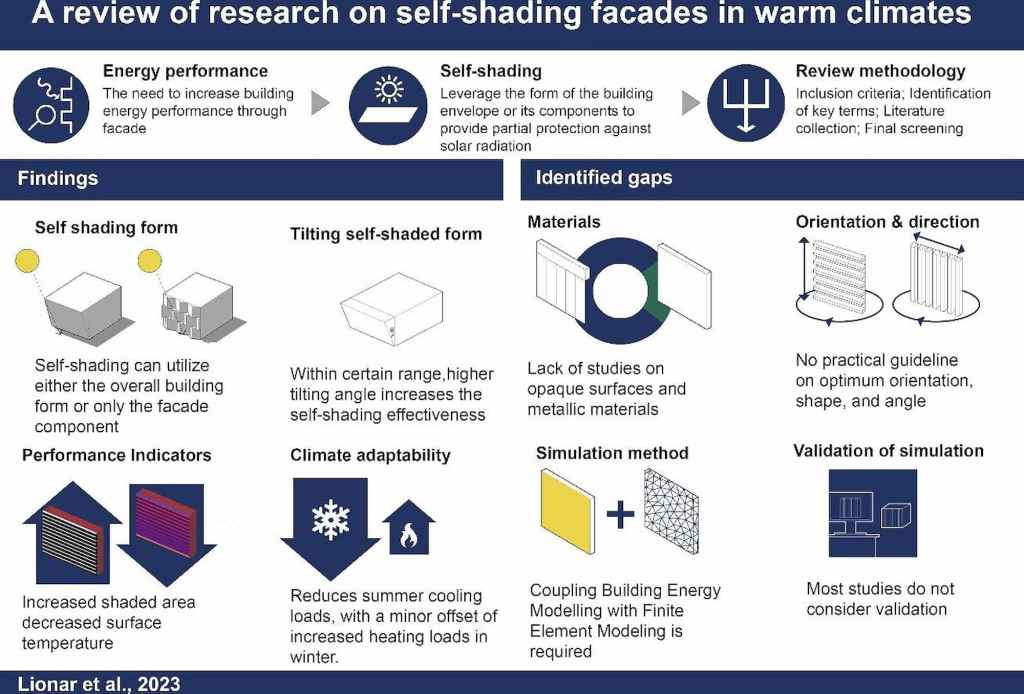

It is regrettable that the concept of self-shading buildings—or formal strategies to mitigate the effects of solar radiation—is so rarely employed. As University of Adelaide researchers argue in Energy and Buildings, there is no comprehensive review of self-shading despite the fact that solar radiation is a crucial and unavoidable phenomenon. In the team’s evaluation of 234 papers, they determined that geometry, self-shaded surface area, and materials are three of the most common considerations.

These topics are inherently connected because solar radiation functions similarly at different scales. The difference between building and material morphology is an artificial distinction given that self-shading can—like fractal geometry—operate at all levels of detail. Precedents that employ self-shading at various scales, as analyzed by researchers at Port Said University in Egypt, include the mosques of Northern Ghana or Madrid’s District C Telefónica building by architect Rafael de la Hoz.

These examples reveal that there is no predominant scale for self-shading; thus, the strategy provides a significant holistic design opportunity.

At the building module scale, a University of Bristol study examines the use of surface texture for passive cooling. Taking a biomimetic approach, the architectural researchers fabricated a series of textured concrete panels based on the morphological principles of elephant skin.

Like many organisms, elephants employ various physiological strategies to maintain a narrow body temperature range, including the intrinsic self-shading and evaporative cooling of their skin. At this detailed scale, the self-shading folds generate convective currents, and the valleys increase evaporative cooling due to their ability to hold additional moisture.

The team cast a series of concrete panels with varying surface area-to-volume (SA:V) ratios. Thermal imaging tests demonstrated that the deeper the texture and the larger the SA:V ratio, the greater the resulting heat loss.

One limitation of self-shading is that fixed geometries don’t adapt to changing climate conditions, such as different seasons. While unwanted during the summer months, solar radiation is typically preferred during the winter. Taking full advantage of seasonal changes requires adaptability. As one solution, an engineering and mathematics team from Columbia University has proposed FinWall, a dynamic envelope system with rotating panels that optimize facade thermal regulation. The researchers focused on tuning the long-wavelength infrared radiation (LWIR), a subset of the electromagnetic spectrum representing radiant heat. The top surface of the fins consists of a high-emissivity coating, while the bottom surface has a low-emissivity coating. In summer, the fins point downward, reflecting solar radiation skyward. In winter, the fins are rotated upward to eliminate radiation loss. Although FinWall has yet to be field-tested in a building application, the research offers a compelling way to impart facades with an unusually high level of thermal adaptability. This novel performance capability—as well as other self-shading innovations—deserves commensurately impressive designs.