Cinematic views of the Getty Center, the Los Angeles skyline, and the Pacific Ocean posed a tall order for architect Ignacio Rodriguez as he designed a home high in the Brentwood Hills. His answer: a sleek, contemporary house that appears to float in mid-air. Retractable glass walls dissolve the boundary between indoors and out, merging architecture and landscape.

“We really opened up the house with walls of glass so suddenly it significantly grows in size, and the lines are blurred,” says Rodriguez, whose firm, IR Architects, is based in L.A. “A bird could fly in and fly right back out, and that feels totally normal.”

Photo by Meghan Bob Photography.

Views of the Getty Center from the Tigertail home in the Brentwood Hills, by IR Architects.

While siting like that feels dramatic, it was more or less dictated, Rodriguez says. “This site had a very small amount of flat area, so half of the house is literally elevated in the air.”

In many respects, Rodriguez’s design captures the essence of California—a breezy, laid-back lifestyle with far-reaching influence on food, fashion, architecture and design.

Historical Influences

California’s architectural identity is shaped by a rich interplay of historical, cultural, and environmental forces. From red-tile-roofed Spanish Revivals and ornate Victorians to low-slung ranches and midcentury moderns, the state’s eclectic built environment reflects the legacy of its diverse population and its long-standing spirit of adaptation.

Temperate weather, abundant local materials, and waves of immigration have further diversified the architectural landscape. By the mid-20th century, innovative designs such as Case Study Houses and Eichler homes embraced open floor plans, expansive windows, and a deep connection to indoor-outdoor living.

“It’s less about a set of rules and more of experimental playfulness that’s made possible because of the climate,” says L.A.-based architect Barbara Bestor of Bestor Architecture. “You could be a lot looser with how transparent and open [the design] might be.”

Photo by Bruce Damonte.

Hilltops Residence in Los Angeles, by Bestor Architecture.

Much of the region’s architectural character took shape as the population surged after World War II. Influential architects and designers—Frank Lloyd Wright, Rudolph Schindler, Albert Frey, Julia Morgan, Richard Neutra, Charles and Ray Eames, and Cliff May, to name a few—embraced informality and flexibility, creating buildings that celebrated natural light, the landscape, and wide-open windows. “They were playing around with geometry that comes from nature and not Platonic geometry,” Bestor says.

Organic Modern

Perhaps more than any other architectural gesture, creating a seamless connection to the outdoors is paramount in California. “It’s our natural human instinct to want to be in nature,” Rodriguez says.

At the Brentwood Hills house with sweeping views, he installed a 65-foot-wide glass wall that fully retracts, dissolving the boundary between the living room and the terrace with its infinity pool beyond. A curved glass staircase encircles an interior courtyard anchored by an olive tree planted directly into the grade-level floor. At the entry, a lush botanical living wall and pivoting glass door greet guests. “Bringing in plants and planting into the ground dissolves the indoor-outdoor boundary,” Rodriguez says. “It feels like you’re in a park.”

Photo by Meghan Bob Photography.

The interior courtyard at the Tigertail home in the Brentwood Hills, by IR Architects.

Views of nature matter just as much at night, Bestor says. She often collaborates with landscape designers to create outdoor lighting that keeps garden views alive after sunset. “As the sun goes down, you can still have an outdoor experience,” she says. “It’s like Hollywood magic to have your garden illuminate at night, and then your windows are functioning as these sort of picture frames to what’s going on outside.”

Even when reviving historic modernist homes, architects are forging new connections with nature through technological innovations—while preserving the original designers’ intent. When San Francisco-based architect Neal Schwartz of Schwartz and Architecture set out to expand a 1966 house in Palo Alto designed by Aaron Green—a protégé of Frank Lloyd Wright—and built by Joseph Eichler, Schwartz asked himself, What would Mr. Green do today?

Photo by Ayla Christman.

The Green House in Palo Alto, renovated by Schwarz and Architecture.

Schwartz knew that preserving the home’s garden-facing glass wall was non-negotiable. “[Green] created his own view on a very narrow lot, and that justified the need for these huge windows,” Schwartz says. “So that was really important to keep, but the windows are entirely rebuilt to be double-paned and energy-efficient. It’s a combination of products and custom woodwork that’s recreated to maintain the essence of what the architect originally had planned.”

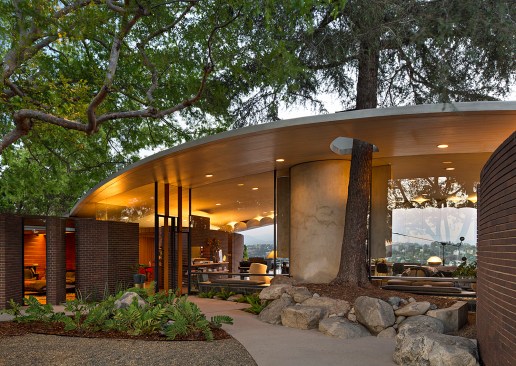

Photo by Tim Street-Porter.

Silvertop in Los Angeles, designed by John Lautner and refreshed by Bestor Architecture.

Bestor employed similar subtle yet impactful enhancements when she refreshed Silvertop, a 1956 house in Los Angeles designed by John Lautner. Her additions build on Lautner’s vision to “achieve a sense of natural beauty by blending [the house] into the natural surroundings,” incorporating elements such as a custom-designed mechanical glass door, automated wood louvers, folding shades for skylights, and retractable glass panels.

Photo by Tim Street-Porter.

Silvertop in Los Angeles, designed by John Lautner and refreshed by Bestor Architecture.

“Many of these older modernist houses did not have a good lighting game,” Bestor says. “A lot of what we did was add a huge layer of technology that’s hidden. We made moving parts move better and faster. Now, there’s tons of light.”

Built-in Efficiency

Today’s technical innovations are making windows more energy-efficient, sustainable, and fire-resistant—especially important in California, where Title 24 building codes sets high standards for energy conservation and sustainable building practices.

“California is really at the forefront of understanding climate change,” Schwartz says. He notes that he often works with energy consultants to “go much deeper into digitally modeling the house to tell you exactly what the environmental human comfort levels are going to be at any time.”

Photo by Richard Barnes.

The Lichen House in the Sonoma Valley, by Schwartz and Architecture.

These restrictions often require ingenuity—and lead to creative design solutions. For the Lichen House nestled in the hills above the Sonoma Valley, where the main views face southwest, Schwartz encountered a challenge: “In that orientation, we would never pass Title 24 to get the windows we wanted,” he says. But by creating a window-lined hallway that didn’t require heating or cooling, the architect was able to offset the windows needed elsewhere.

“That space can be closed off and considered kind of an outdoor space that acts as a buffer zone to the bedrooms and the rest of the house,” he says. “We came up with a creative solution first just to meet code, then we realized, this is actually really great. It’s more sustainable and keeps the energy costs down. It’s more sustainable and keeps the energy costs down.”

Photo by Richard Barnes.

The Lichen House in the Sonoma Valley, by Schwartz and Architecture.

Glass performance is another key factor for houses designed to withstand wildfire. In addition to thermally broken aluminum frames and tempered glass, sprinklers beneath the eaves offer another layer of protection, Rodriguez says.

“The fire is going to want to come in through the windows and doors, so that’s where the vulnerability is,” he says. “Building tight envelopes so your house doesn’t draw in any smoke from the outside is important. We also have a series of filters to keep those particles out, so it’s about looking holistically at the entire structure to get it to perform better. We want to make sure that the house is as fortified as it can possibly be for the future.”

Creative Solutions

California often leads the way in design solutions that confront complex challenges. For architects, that ingenuity plays out in varied and creative ways. In remodeling the Green house, Schwartz modified the roofline where the original carport no longer met code for the height of modern cars.

Photo by Ayla Christman.

The Green House in Palo Alto, renovated by Schwarz and Architecture.

“We needed to lift it, so we changed the angle slightly and rebuilt the scupper,” he says, referring to the mechanism that collects and redirects water away from the house. Today, the more pronounced scupper has become a design feature—functioning like mini waterfall in the landscape when it rains—while a new sunken family room occupies the space that once was the carport.

Photo by Ayla Christman.

The Green House in Palo Alto, renovated by Schwarz and Architecture.

As carports—once iconic in California modernist design—have largely disappeared, garages are evolving into bespoke destination spaces that celebrate the car. “They’re an art piece in itself,” Rodriguez says. “What once was a throwaway 400 to 600 square feet is now an extension of your house.” The so-called “jewel boxes” are often encased in glass, temperature-controlled, and designed to showcase both vehicles and other passions, such an art collection and lounge areas.

Photo by Sean Costello.

A Beverly Hills garage that celebrates the car, by IR Architects.

“We are reinventing all of these different spaces,” Rodriguez says. “Whether it’s reimagining a garage, redefining a kitchen, or creating a 40-foot opening, it all can be done. The technology exists. There are always new concepts that are being created, and I think they are magical.”

For more on designing with nature, wellness, and modern design principles in mind, explore the series Framing the Future: How Design Is Reshaping the Way We Live.