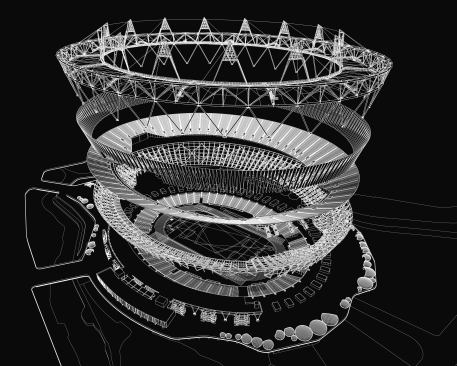

Populous

London 2012 Olympics Stadium Axonometric

ARCHITECT’s contributing editor Blaine Brownell wrote that Beijing marked the beginning of design’s ascendency for the Olympic Games. Do you think this is true?

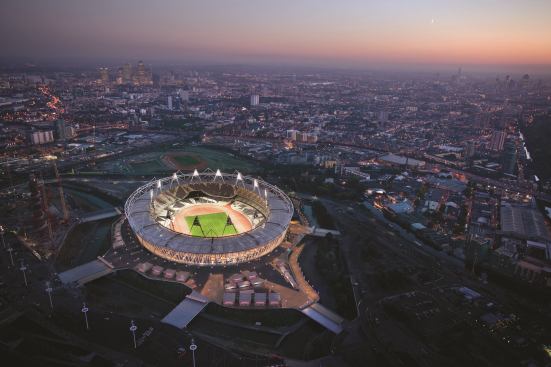

I think that is true, but there just can’t be a comparison between Beijing and London. The great thing about the [London] Olympic Park is that it truly is a park and people treat it as a park. It’s a lovely setting, and a completely different environment to Beijing, which had a lot of hardscaping. London is very tactile and you can get so many different experiences in London’s Olympic Park that Beijing didn’t offer. There’s also a variety of architecture; it doesn’t look as if it had all been built at once by one vision. But the profile of design has definitely risen. The London Organising Committee for the Olympic Games had a design principal—Kevin Owens, a British man educated at Yale—and that hasn’t been done before from the client side, to ensure that design matters—not only at the park, but across all the venues. How does the emphasis on sustainable design tie in to the emphasis on a more aesthetic Olympic Games?

If you Google “1992 Barcelona Olympics diving,” you’ll find a diver in front of Gaudi’s Sagrada Familia. What we did is say, we want all of these London iconic backgrounds. The whole idea was that after the Olympics, we wanted the city to still resonate with people. There is an economic component to sustainability, which includes tourism. One of the reasons a city bids for games is for tourism for years if not decades afterwards. That happened in Barcelona, Athens, and Beijing. It’s not just about the 9 million who attend but also about the 4.7 billion TV viewers and the countless billions of print media readers. We’re trying to inundate the media with London.

What lessons have you learned from Olympic project failures in the past, both yours and others?

They had some transportation challenges in Atlanta in 1996, and one of the things we definitely learned is how to design our venues with the transportation in mind. And we’ve learned how to be smarter about how we showcase the city; we’ve done it in a minor way before, but not nearly to the way we’ve showcased London this time around. Also, because we had so much temporary structures, it was important that we had a consistent vision across the board. We want a spectator to have a similar experience at each place, so we created a kit of parts, effectively a guide book. When we talk about having 80 architects, and all these different venues … we needed budget control and operational consistency. From a logistical point of view, it’s a massive logistical and design undertaking. We wanted to push the edges of what it could be. Two-thirds of the Olympic Stadium is temporary. Only one-third permanent. What we’ve learned is that it’s not just about the big iconic moments. We’ve designed things at an appropriate scale.

Are temporary or flexible stadiums the way of the future?

They have to be. Bidding cities are finally going to see that this is the way that you don’t put such a hard burden on a city for decades to come. Within the last year or two, Montreal finally paid off its debt from the ’76 Olympics. That [the debt] is not an option anymore. It’s in the International Olympic Committee’s best interest to ensure that more and more cities can bid. Rio de Janeiro is a prime example: They’re an emerging economy, and 2016 will be one of the first times that the Olympics has gone to an economy like theirs. That in itself is pointing in the right direction.

What have you learned from this stadium that you’ll take to the next one, after Sochi in 2014?

It is about getting the approach at an appropriate scale. That’s what’s nice about London; it is all these temporary structures. What you don’t normally see [with Olympic buildings] is the long-term life-cycle cost: paying the utilities, upkeep, staff wages, furniture, you name it. We talk about the iceberg theory; the tip above the water is the front-end cost to build the stadium. The rest is your life-cycle cost for the next 30 to 40 years. But if you build temporary, then you save life-cycle costs. Then you don’t put that burden on the city. It takes the client to have the same vision, and they have to push that through, but we’ve learned to talk to a client and get it right for their city.

What can you tell us about the Winter Olympics Stadium in Sochi?

I can tell you that we’ve designed into that stadium more flexibility to do more extravagant things than London. They’re planning to put on one heck of a show. The client was a big fan of Stadium Australia [aka ANZ Stadium, also designed by Populous] as well as a stadium in Hong Kong, the Hong Kong Jockey Club [by Populous]. Both of those stadiums have a similar approach: a canopy that covers the seats in a long arch, to cover all the way to the edge of the field. We also knew that at the Sochi stadium, one end was facing the sea, and one was facing the mountains. We created a stadium that had open ends, for these surrounding vistas. How many stadiums have views of mountains and sea simultaneously?