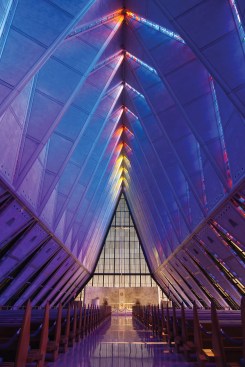

The Cadet Chapel at the U.S. Air Force Academy, near Colorado Springs, Colo., is a masterpiece of glass, steel, and aluminum. Designed by the late Walter Netsch of Skidmore, Owings & Merrill (SOM), the multi-denominational chapel was completed in 1963. With its stunning ribbons of stained glass and 17 identical spires that pierce the sky, the building’s expressionistic design (Time magazine dubbed it “Air Force Gothic”) stands in glorious counterpoint to Netsch’s low-slung, horizontal collection of buildings elsewhere in the Cadet Area, the academy’s academic and residential core.

Netsch’s bold design for the academy was highly controversial when first conceived in the 1950s. Today, it’s considered one of the prime examples of postwar Modernism, a kind of Rocky Mountain Brasília. And despite a few regrettable additions and alterations over the years, the Cadet Area—a National Historic Landmark District—has remained largely as Netsch envisioned it.

Magda Biernat

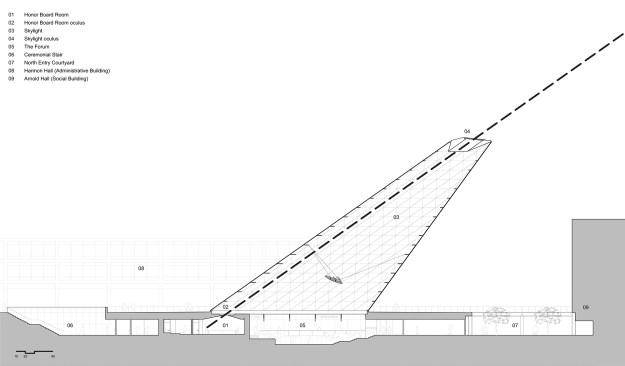

Polaris' tower, which is canted at a 39-degree-angle to align with the North Star

But there’s a new kid on campus: the Center for Character & Leadership Development (CCLD), informally known as Polaris Hall. Designed by Roger Duffy, FAIA, of SOM’s New York office, the $40 million, 46,500-square-foot building—funded by a combination of tax dollars and private donations—is the most significant addition to the academy in decades. The tilted tower, a short walk from the chapel, both pays homage to Netsch’s rigorous Modernism and is also a radical departure from it. Duffy insists the CCLD is appropriately scaled and “respectful” of Netsch’s original buildings. But there’s no doubt that it steals some of the chapel’s architectural thunder.

Surprisingly, there’s been little controversy over the new building, which finally opened in April after numerous construction delays. (Early on, workers digging the foundation encountered a boulder the size of a semi-truck, and later it was discovered that the tower was about an inch out of alignment. Last fall, just as the building was about to finally open, a pipe in the fire sprinkler system burst, causing extensive damage—and more delays.) Although SOM’s design was widely published online when ground was broken in 2012, the completed structure has received scant attention, even among architects and critics. So how did a 105-foot-tall glass-and-steel tower end up rising in the middle of a National Historic Landmark District?

Magda Biernat

The Forum, a gathering space for meetings and talks

Daniel Bourque

Cadet Chapel interior

It helps to understand that one of the academy’s stated goals is to train and develop “leaders of character.” Cadets pledge to adhere to an honor code: “We will not lie, steal, or cheat, nor tolerate among us anyone who does.” Those words are inscribed in large letters on the academy’s Honor Wall.

But the academy has been plagued by scandal over the years. In 2003, numerous charges of sexual assault resulted in the removal of four top officers, including the superintendent. Two years later, critics alleged that some academy staff members were pushing evangelical Christian beliefs on cadets. And most recently, in 2014, 40 freshmen were suspected of cheating on a chemistry assignment (10 of the students were found guilty).

In 2005, then-superintendent Lt. Gen. John F. Regni began exploring the idea of a dedicated building for leadership and character training. As Regni recalled in a 2012 paper, the academy’s mandatory leadership classes were “somewhat general [and] cursory,” and they were held in classrooms scattered across the campus. Honor code hearings were conducted in a windowless conference room in Fairchild Hall, the main academic building. “It became obvious the core mission of the academy was being accomplished on the cheap,” Regni wrote.

At the urging of a group of influential alumni, Regni developed a plan for a new facility that would make a powerful statement about the importance of moral and character education. “It became evident,” Regni wrote, that the building deserved to be “the next iconic structure after the chapel.”

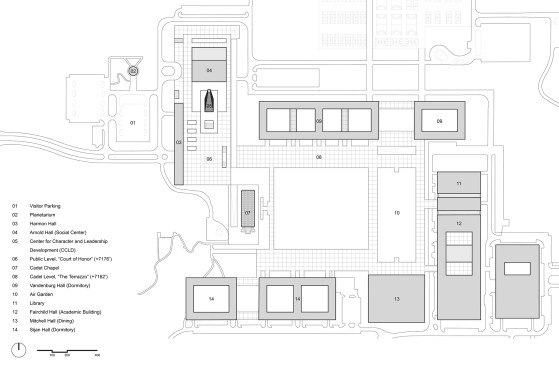

Site plan for the Cadet Area

Duane Boyle, AIA, is the academy’s resident architect. “We knew that putting an iconic building into what’s considered the heart of the historic landmark district could be very controversial,” he says. Boyle, a civilian, is not your typical government bureaucrat. He grew up in a neighborhood outside the academy’s south entrance and was inspired to become an architect by his frequent visits to the campus. He even worked for a time at SOM. At the academy, he led the effort to get the Cadet Area listed as a landmark. At the same time, he insists, “We’re not just this architectural gem that’s stuck in time. We’re a university campus, and you have to evolve.”

Regni and Boyle both agreed that any new building should be grounded in Netsch’s architectural principles for the academy, and that it had to be a complementary structure, not one that would detract from the Cadet Area’s historic character. They concluded that the best firm for the job was the one that had designed the academy in the first place: SOM. Boyle contacted the firm’s New York, Chicago, and San Francisco offices. “Each jumped at the opportunity,” says Regni. “We decided to open a friendly competition, pitting each office against each other to independently develop their own design.”

Magda Biernat

Interior detail of the tower

In New York, Roger Duffy felt the weight of the assignment immediately. “It was a very imposing challenge,” he says. “We weren’t exactly sure how to approach the project. It took us a while to get our heads around it. I mean, the last thing anyone wants to do is make a wrong move at a place like that.”

Although Duffy, 59, had once met the famously irascible Netsch in Chicago (“He was a big man with a booming personality,” Duffy recalls), he had never visited the academy. So he flew to Colorado Springs and toured the chapel, of course, with its dramatic tetrahedron-and-stained-glass interior. But he also took note of the stunning assemblage of buildings designed by Netsch using a 7-foot organizing grid, and the immense plaza known as the Terrazzo, where freshman cadets (“doolies”) are required to jog to and from classes in straight lines formed by marble strips, one of many strict rules imposed on first-year students.

“I was quite overwhelmed,” Duffy recalls. Visitors to the academy enter the Cadet Area at its highest point, which offers a stunning view of the entire site. “You sort of look out and down over the campus. You just in one gestalt moment ‘get it.’ Somehow I didn’t think it would be so powerful, but it is. I love the level of rigor that Netsch and [Gordon] Bunshaft”—SOM’s longtime chief of design—“imposed on everything.”

Magda Biernat

Aerial of the chapel (left) and Polaris (right)

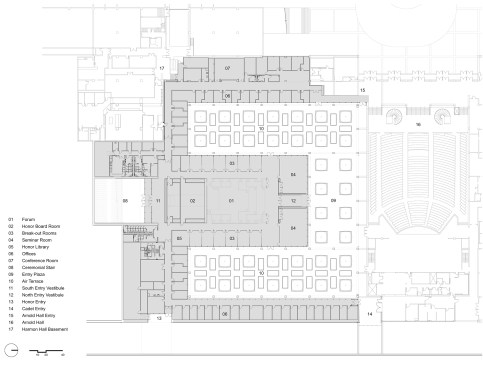

Academy officials wanted the building to be in a prominent location, and they zeroed in on an area called the Honor Court, a large public plaza not far from the chapel. Duffy chose a site on the north end of the Honor Court, adjacent to Arnold Hall, a white-marble box that serves as the academy’s social hall. Much of the CCLD is set below the plaza, in a little-used former courtyard space. Visitors enter the building by walking down a wide granite staircase from the plaza level. Classrooms, meeting rooms, and offices ring the remaining courtyard, allowing natural light to stream in.

Inside, Duffy adhered to Netsch’s 7-foot grid, and he used materials—such as Murano glass tiles on the walls near the main entrance—that mimic those found elsewhere at the academy. (It was Bunshaft who suggested the use of red, blue, and yellow Italian mosaics at vestibules.)

Magda Biernat

Section of the tower

The CCLD’s most striking feature is the tower canted at a 39-degree angle in order to align with the North Star, symbolizing the academy’s “unchanging core values,” Boyle says. The tower’s four sides taper to a squared-off roof containing an oculus. From inside the CCLD’s Honor Board Room, a cadet accused of violating the academy’s honor code can look up at night and see Polaris through the opening, an intimidating reminder, perhaps, of the value of a moral compass. The glass tower also serves as a majestic skylight for the CCLD’s “forum,” a large gathering space for meetings and TED Talk–style events, which is located next to the board room but doesn’t share the same alignment with Polaris.

Duffy concedes the CCLD’s tilted tower is a departure from the academy’s strict geometric grid, with its abundance of straight lines and right angles. Previously, only the expressionistic chapel stood apart from the orderly rationalism of the other architecture. While the CCLD isn’t as massive as Netsch’s celebrated building, it does compete with it visually.

Magda Biernat

The Honor Board Room

Polaris Hall plan

Duffy insists the CCLD is appropriately scaled and “respectful” of the chapel and Netsch’s other buildings. He intentionally placed the tower’s steel trusses on the inside, with smooth glass on the outside, in order to make the building even less sculptural than it is. “If we had inverted the structure and put it on the outside,” he says, “I think there would have been more tension between the CCLD and the chapel.”

The competition’s other entries were by Brian Lee, FAIA, a design partner with SOM’s Chicago office, who conceived of a cylindrical building—also next to Arnold Hall—comprising a structural steel “basket” surrounded by glass; and Craig Hartman, FAIA, a design partner based in SOM’s San Francisco office, who chose a site somewhat closer to the chapel for a striking glass box supported on the inside by a series of angled steel struts.

The jury was made up of academy officials (including Regni) and two prominent architecture scholars—Joan Ockman, then-director of the Temple Hoyne Buell Center for the Study of American Architecture at Columbia University, and Kent Kleinman, AIA, dean of Cornell University’s College of Architecture. They had “a good deal of debate” over the three entries, as Ockman recalls. In the end, Duffy’s design prevailed, she says, because “it calls attention to itself as a leadership center” while keeping a respectful distance from the chapel. It helped that much of the building is set below the plaza level.“It was a difficult task to design a building that would fit right in to that campus, rather than to site it off the main grid. That would have been much easier,” says Ockman, now a distinguished senior fellow at the University of Pennsylvania School of Design. But Duffy, she believes, really pulled it off.

An advisory panel that included Joseph Saldibar, architectural services manager at the Colorado Historical Society; Tom Keohan, historical architect at the National Park Service; and Robert Nauman, an architectural historian at the University of Colorado, also signed off on Duffy’s design. “We felt that it was the most compatible with the academy’s existing architecture,” Keohan says, “and had the least impact on the historical integrity of the site.”

Not that they could have stopped the project. Saldibar points out that any changes to National Historic Landmarks proposed by federal agencies are subject to the Historic Preservation Act’s Section 106 review process, but that the process is limited in what it can achieve. “We have the ability to make recommendations on the proposals, and under the law, the academy is required to take those recommendations into account. But they’re not required to change anything. They can really choose to do pretty much anything they want in a historic landmark district: Add buildings, tear down buildings, significantly alter buildings.”

Magda Biernat

The Forum

Says Nauman: “I hate to say that nothing is holy in architecture, but the fact is, needs change over time, and the academy is a campus with 21st century needs. You can’t just preserve it in amber.”

As he sees it, the CCLD symbolically shifts attention away from a religious building—“meant to be a marker in the Cold War against godless communism”—to a secular building. “And that’s more appropriate in today’s world.”

What would Walter think? “I suspect he wouldn’t be particularly favorable about drawing attention away from his chapel,” Nauman responds.

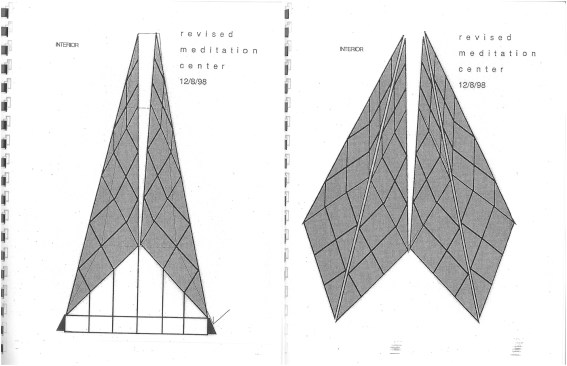

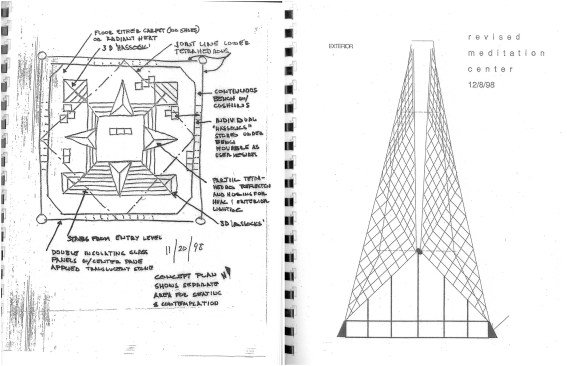

Boyle, however, thinks it’s highly possible that Netsch would have approved of Duffy’s design. In the late 1990s, he says, Netsch drew up conceptual plans for a “meditation center,” a response to increasing demand for worship space from alternative religious groups at the academy. “It was a triangulated glass building with a squared-off cone,” Boyle says, “a very towering structure, similar to SOM’s design for the new building. But it was even taller, and would have been closer to the chapel.”

Netsch's 1998 concept for a proposed meditation chapel, which would have been located near the chapel

It was never built, but Boyle believes it demonstrates that Netsch, who died in 2008, wasn’t opposed to architectural alterations at the academy, even in the hallowed Cadet Area.

In any case, Polaris Hall seems to have been largely embraced by students, faculty, and administrators. As for the architectural community, “there’s been practically zero interest,” Boyle says. “It’s really odd.”

Still, Boyle, whose next project is a long-planned restoration of the Cadet Chapel, seems relieved to have dodged a bullet. “I did what I could to try to head off any controversy,” he says. “So far, there hasn’t been any, but it could still happen.”