Robert Irwin is all about context—or, more to the point, our perception of context. For close to four decades, he’s made art about how we see place and atmosphere: His gallery installations transform lowly fluorescent tubes and fabric scrim into otherworldly environments, and his carefully attuned landscapes offer up meditations on color, light, and time. His precise placement of one light bulb or one tree might lead viewers to reconsider their understanding of a window, a painting, or even the sky. So it’s a wonder to learn that the artist’s studio is no place of any note—a rental unit among a series of roll-up doors in a nondescript warehouse just north of La Jolla, Calif.

Inside, multi-hued, unlit fluorescent tubes form patterns across white drywall—an almost painterly body of new work. On a recent afternoon in his back office, on a phone call, Irwin says, “Just don’t complicate things.” It’s a tall order for the artist, 87 years old, who’s at work on one of his most complicated projects to date. Commissioned by the Chinati Foundation, the contemporary art museum in Marfa, Texas, founded by Donald Judd, the piece reconfigures an existing U-shaped army hospital compound into a site-specific sculpture. The 10,000-square-foot project opens in July.

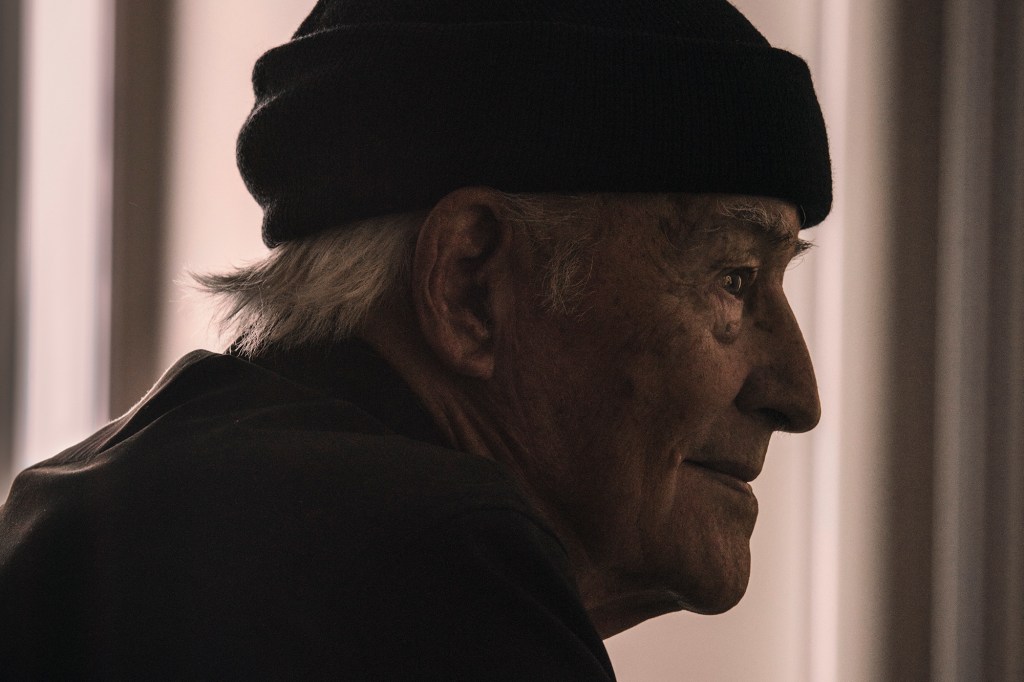

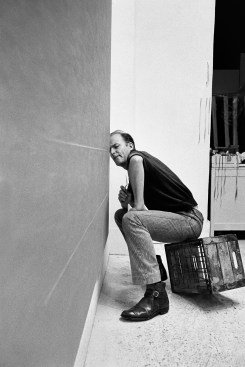

Mark Mahaney

Irwin in his studio

Mark Mahaney

Detail from Irwin's studio

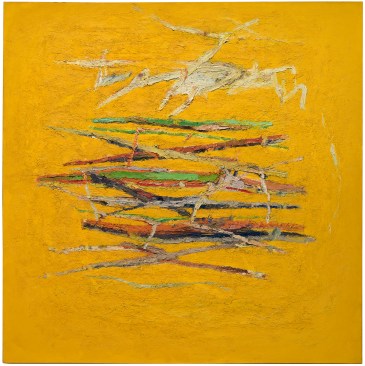

But first, in May, the Hirshhorn Museum in Washington, D.C., will present the exhibition “Robert Irwin: All the Rules Will Change,” an extensive survey of his work from 1958 to 1970—a period that begins with his abstract painting and ends with his total reconsideration of materials and the gallery setting. Irwin is considered one of the key members of the Light and Space art movement (along with James Turrell and Larry Bell), and the exhibition tracks how within just a dozen years, the artist’s framed oil canvases gave way to ethereal works that defy conventions: acrylic paint on aluminum discs that seem to float in space.

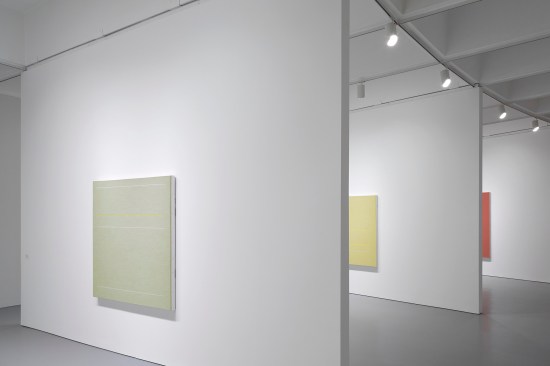

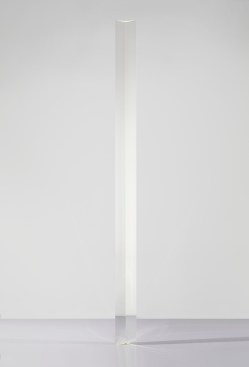

Cathy Carver

Irwin's abstract paintings on display at the Hirshhorn

Cathy Carver

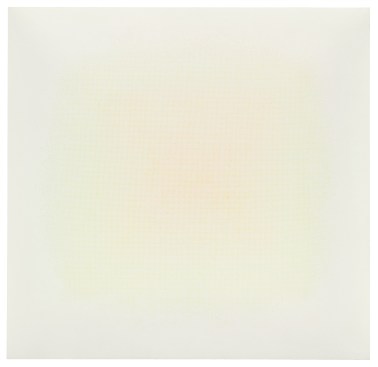

Untitled (1969) on display at the Hirshhorn

The show will also include a new installation, one that continues Irwin’s explorations with architecture. The artist will take a curved gallery in Gordon Bunshaft’s cylindrical Brutalist museum and “square” it using 100 linear feet of floor-to-ceiling scrim. The scheme was the artist’s Plan B. Like many before him, he was wooed by the building’s open-air ground floor and proposed a series of floor-to-ceiling scrims that would attach to the exposed structure of the donut-like building above and follow the existing pattern of the architecture’s underbelly. “I thought if I stretched a scrim on every one of those coffers, which curve all the way around, it’d be like when you turn a mushroom upside down, with that whole feathering kind of thing,” Irwin recalls. “And when the coffers are all lit, it would’ve been sensational, beautiful.”

And then came bureaucracy. According to Irwin, the museum’s engineers fretted that the scrims would act like sails, blowing in the wind and causing the assembly to unseat and lift the plaza’s granite pavers. Irwin didn’t give up the fight easily. He had his team make a mock-up of the proposed frame and stretch material over it. “And then I said, ‘Okay, point load this thing. Fifty pounds, 100 pounds, 200 pounds.’ We get up to about 550 pounds and what happens? The staples come loose. And there’s your answer. That’s your fail proof,” he says with both pride and exasperation at having proved the engineers wrong.

Frederick Charles

Irwin's scrim test for his initial Hirshhorn idea, which was performed at Cuesta College in San Luis Obispo, Calif.

It’s not his first (or likely the last) time that he has clashed with the design world. When Arata Isozaki, FAIA, was designing the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) on Grand Avenue in Los Angeles in the early 1980s, Irwin (then an art adviser to the museum board and a friend of the Japanese architect) wrote up his own brief for the project. A review in The Washington Post when MOCA opened in 1986 suggests that Irwin’s influence is seen in the building’s signature pyramid, especially where the distinctions between wall and ceiling begin to blur.

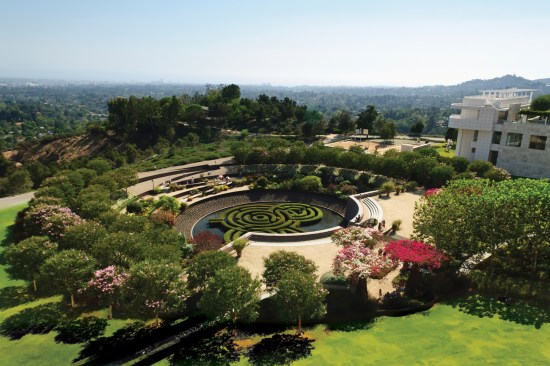

A decade later, Irwin famously brawled with Richard Meier, FAIA, the architect of the Getty Center in Los Angeles, over the center’s Central Garden, which Irwin was asked to design. It was a tug-of-war between the architect’s limestone, processional geometries and the artist’s naturalist, process-driven proclivity for a landscape that responded to the canyon site and the changing seasons. Lawrence Weschler famously chronicled the saga in Seeing is Forgetting the Name of the Thing One Sees (University of California Press, 1982), his book on Irwin, titling the chapter “When Fountainheads Collide.” As with such battles of will, it was a draw, or as the artist described it to Weschler, “counterweights.” While the organic forms were slightly tamed to fit Meier’s taste, Irwin’s hands-on process remained unswayed.

The Getty Center's Central Garden, which was designed by Irwin

When asked in the late ’90s by Michael Govan, then-director of the Dia Art Foundation, to design the museum’s new space in Beacon, N.Y., Irwin approached the project as a procession of experiences beginning at Grand Central Station and continuing along the hour-and-a-half train route to the small town. He moved his family to a house across the river from the site, an old Nabisco box-factory, and worked with the then-emerging, now-disbanded firm OpenOffice on renovating the building into a space for contemporary art. By his telling, the young firm’s role was to play by his rules and, of course, pull permits.

“It was an education like no other,” recalls Los Angeles–based Linda Taalman, AIA, who was a member of OpenOffice. The Dia:Beacon was her first job out of Cooper Union; she worked directly with Irwin for four years. “He worked tirelessly on hand-drafted drawings at his desk for the museum and its gardens, including detailed stair and gate drawings,” say Taalman. “Sometimes the collaborative team of the architectural process slows you down, and he showed me how singular decisiveness can be extremely effective. Architectural discipline and training often lead to overwrought design solutions that are at the service of making sure the architects’ presence is known. Irwin often worked towards the opposite, at making the presence invisible. There were times where he made his presence known, when there was an opportunity for pause, but the majority of the time his was a touch that worked towards seamlessly merging with the environment.”

Photography by Cathy Carver

Untitled (1963)

Photography by Cathy Carver

Untitled (1970)

One shouldn’t confuse Irwin’s approach to his art/architecture as a myopic expression of ego, however. Dressed in a Coca-Cola baseball cap and jeans on the recent afternoon I met him in his La Jolla studio, he’s more shaman than Howard Roark. He tries to coax something transcendent out of the context—to summon latent sensitivities from the ordinary mix of buildings, cities, and landscapes. In truth, his process bears some resemblance to an architect’s site visit.

“Well, you start at the site. You look at the site, try to figure how this site came to exist,” he begins. “You know, it sounds ridiculous, you run your sensibility over it, you run your hands over it, and you look at all the things that make up the site. What kind of materials? How do you enter, where do you enter from? What are the events that take place there? How is the existing context with everything? You start making a wider circle. And you make a circle, a wider one and a wider one. And you realize, when people come to a site, they don’t come from nowhere, they come from somewhere. And so how they come has a big bearing on how they’re going to experience it—you don’t ignore all that. In the beginning I’m looking for … I have no idea what I’m going to do, so I’m looking for something to hang my hat on. And so it goes backwards.”

Marvin Silver

Irwin in 1962

Irwin remembers Marfa before it was Judd’s stomping ground and part of the global art hajj. He stopped there in the 1970s because “it was the only place to get gas anywhere between there and hell.” As it happened, he ran into Judd who was then scouting out the town.

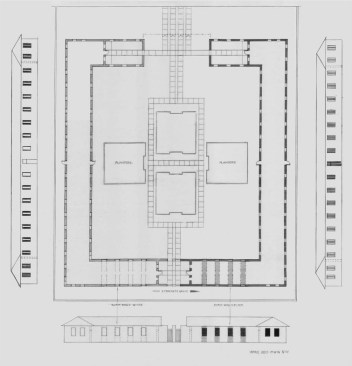

The Marfa project Irwin is working on now—an artwork in the form of a building—began with an invitation in 1999 from Chinati; it is the foundation’s first addition to its permanent collection since 2004. The site is the abandoned Fort D.A. Russell hospital, which was built in 1921 and decommissioned in 1946. The building sits in a field just across the road from Judd’s original property, on land gifted to the foundation with the express intent of having Irwin develop a proposal for the site. Windows railroad down the face of the low-slung structure; the pattern is mirrored on both the courtyard and outer façades. Irwin was struck by how such an alien, boilerplate structure could look at home in the desert. “There’s something really interesting—just a little side thing—all that architecture down there [in Texas] is not architecture in the normal sense,” he explains. “Somebody [designed] this thing in Washington, D.C., who maybe never was in Marfa. But those barracks, they work. I mean there’s something about them. They’re right for the place.”

Courtesy The Chinati Foundation

Irwin's plan for his Fort D.A. Russell hospital installation

Irwin’s design treats the architecture as a lens—the openings are apertures; one side of the compound is dark, the other is light. Gray-tinted material applied to the glass will gradate the light entering the space. Inside, white and black scrim walls will modulate how a visitor moves through the space. This mechanism of scrims, tints, and apertures will no doubt be installed with the artist’s meticulous attention to detail (the window sills were raised to his eye level), offering up a view of clouds racing across the vast West Texas sky. Irwin’s efforts lead to simplicity: light, dark, and sky.

“So, basically if you take light as a sense of space, a sense of flow, how things act, what are the progression of steps you have through this, then everything else is secondary,” he says. “What the surfaces are and all those things, they all have to live up to it. But the name of the game is finding that, you know. And to me, that’s what I do. Finding more materials to capture light. Hopefully I got a shot here.” He then adds a coda: “And if the sky does what it does, I’m gonna be dipped in shit, coming up smelling like a rose.”

Phillip Scholz Rittermann

Ocean Park (1959)

Robert Irwin's "Squaring the Circle" at the Hirshhorn Museum