The thing I’ve never understood about the perennial rants against starchitecture—or, as it was labeled in a recent New York Times op-ed screed, “celebrity architecture”—is that they’re always based on the assumption that there are only a handful of buildings worth discussing at any given time, and that they’re always designed by the same people: elitist, indifferent, concerned only with creating, as another recent tirade put it, “exaggerated sculptural form.” In truth, the world is full of architects. There are over 100,000 in the United States alone, over a million worldwide—and most of them are not celebrities. A surprising number of them manage to do great work—sculptural and otherwise—while remaining relatively obscure.

Which is why I found the new book 30 Years of Emerging Voices (Princeton Architectural Press, June) so refreshing. It’s a compendium of all the honorees from the Architectural League of New York’s Emerging Voices program. Launched in 1982, it assembles a group of North American practitioners (from the U.S., Mexico, and Canada) who exemplify the best in architectural thinking in any given year. Selections are based not simply on form and function but, according to the league’s program director, Anne Rieselbach, who has run the search and selection process since 1986, considerations like community involvement and unusual practice models: architects who fabricate building components, run design/build practices, or act as developers, for example. Each year, from a group of 50 invited candidates, a jury of architects, journalists, curators, and league board members select eight firms. The principals are generally youthful but also have done enough work—built and on the boards—that they demonstrate knowledge of who they are as a practice and where they’re heading, that “they’ve found their stride,” as Rieselbach says.

Revisiting three decades of winners as a continuum is

revealing about what architecture truly is: not the province of a few

celebrated practitioners, but an ongoing process of invention and reinvention by

a multitude of talented and thoughtful firms. “One thing [the book] does is it

valorizes smaller to mid-sized practices,” says Rieselbach. “The fact is that

the really good work across the country is done by people who are known regionally,

but that the public doesn’t know.” It’s true that many of the League’s

choices—Steven Holl, FAIA (1982), Tod Williams, FAIA (1982, before Billie Tsien, AIA, was his

partner), Lake | Flato (1992), and SHoP Architects (2001)—later achieved widespread

prominence. But the compendium, in its expansive depiction of the profession, rebukes

the whole notion of starchitecture.

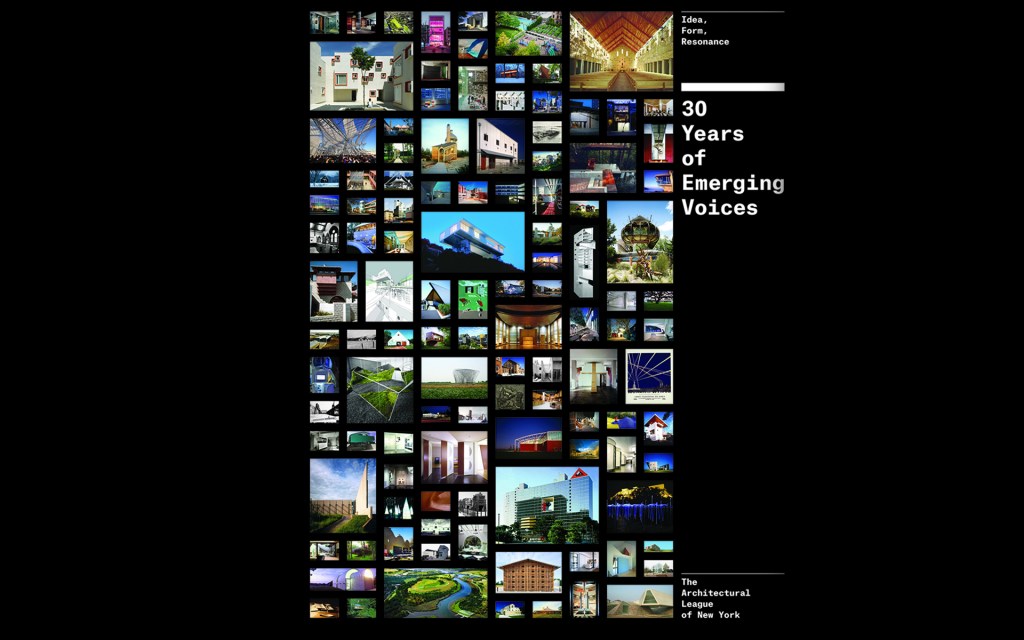

Tightly formatted by the design firm Pentagram, the book

includes essays and overviews by architect and educator Ashley Schafer,

consultant and former director of the Cranbrook Academy of Art Reed Kroloff, and architectural

adviser Karen Stein, as well as short pieces by a variety of critics and practitioners

that reflect on each five-year interval. Primarily, there are pictures—four to

six of them per page, densely arrayed—of the work of some 250 individuals or

firms arranged chronologically, by the year of selection. Each page contains

examples of the work for which each firm was chosen, and selections of the

projects each went on to design. Unlike a retrospective, in which the works and

participants are chosen by curators at one specific moment in time, this book represents

a collection of decisions, made year after year, about what constitutes good

and important architecture.

The essays are perceptive. Kroloff, for instance, notes that the decades covered by the book are the ones in which the computer supplanted the drafting table: “Not since the arrival of the steel frame and the mechanical elevator has the profession gone through a more fundamental reordering,” he writes. “What does that reordering look like?” he asks. “Well, a lot like this book.” In a commentary pegged to the years 2004 to 2008, critic Alexandra Lange considers the phrase “joint creativity,” which Denise Scott Brown used to express her outrage at being ignored by the Pritzker Committee. Lange sees, in her assigned years, a move from solo practices to firms clearly designated as group endeavors. “Putting two, three, four, or five names on the door makes a tremendous difference and diminishes no one,” she writes.

Larger themes aside, I would suggest flipping through the book

for pure pleasure. What a fabulous ride: It begins in 1982 with Susana Torre’s

pencil drawing of her master plan for rehabbing Ellis Island. And it ends in

2013 with SO—IL , the partnership of Florian Idenburg and Jing Liu, and their

steel mesh covered Kukje Art Gallery in Seoul. In between are over a thousand

projects, built and otherwise. They straddle movements from Taft Architects’ (1982)

not-too-referential Postmodern Talbot House to Mark Goulthorpe’s (2009) feverishly

parametric ceiling for One Main, a Cambridge, Mass., office building.

Perhaps one reason I find this compendium so fascinating is that it also happens cover the entire span during which I’ve paid attention to architecture. There are projects I’ve long loved: the Hodgdon Powder Facility, a silvery Quonset hut containing a gunpowder maker’s offices in Herington, Kan., designed by Kansas City-based El Dorado (2008), or the Jamie Residence, a simple, elevated, rectangular hilltop home in Pasadena, Calif., by Los-Angeles-based Escher GuneWardenena (2006). And there are projects I’ve never encountered before, by firms I’ve never thought much about: the Hobbs residence by New York’s Kiss + Zwigard (1993), for instance, which looks like a little factory building in the upstate woods, or a series of modest Montana ranch buildings by Fernau + Hartman (1985), or a bamboo clad barn in Goshen, Ky., by de Leon & Primmer Architecture Workshop (2011).

And then there are projects that I’d seen, but had entirely forgotten,

like the Bridge of Houses proposal, Steven Holl’s 1979 idea about how a certain

defunct elevated rail line in the far West Village could be reused, a curious precursor

to the High Line. On the same page is Holl’s 2009 Vanka Center in Shenzhen,

China, which he’s described as a “horizontal skyscraper”—a long building that

hovers on piers several stories above the ground. The book’s layout makes

obvious the kinship between Holl’s somewhat outlandish Bridges of Houses concept

and his more pragmatic recent commission.

And on and on: the book is as profuse as

an old Sears catalog, and as much fun to thumb through. But the best thing

about 30 Years of Emerging Voices is how

it undercuts the popular notion that architecture is a narrow profession. Sure,

if you want to pen a jeremiad about exaggerated sculptural form, you’ll find

the ammunition here. And if you want to subject architecture to the Mom test (It looks like it comes from a junkyard!)

as that New York Times op-ed piece

did, you’d have no shortage of material. But if you approach the book with an

open mind, without an ax to grind, you’ll discover a discipline that is

remarkably non-elitist and bountiful. The starchitect that

everyone is so bent on discrediting? He’s nothing but a

straw man.