Plastic is the ultimate imitator. Since its inception in the 19th century, plastic has consistently emulated life—first in appearance and, more recently, in function and behavior. From Bakelite’s substitution for scarce natural materials like amber to today’s polymers that heal themselves or change shape, plastic has evolved into a substance that reflects life’s ingenuity—but not without ecological challenges.

Plastic’s story is one of innovation tempered by unintended consequences. Its versatility has made it indispensable in modern society, yet its impact on human and planetary health is undeniable. Microplastics now infiltrate ecosystems, petrochemical production accelerates climate change, and plastic waste chokes our oceans and landscapes. As plastic strives to mimic life, it paradoxically undermines the very systems it seeks to imitate.

The first generation of plastic focused on aesthetic mimicry—faux-wood vinyl siding, countertops that resemble stone, or upholstery that passes for leather. But today’s plastics go beyond appearances, replicating life-like functionality. Self-healing polymers, for instance, repair themselves after damage. For example, researchers at Spain’s IK4-CIDETEC Research Center developed a polyurethane elastomer that can heal cuts at room temperature without external stimuli. Similarly, a NASA and University of Michigan collaboration resulted in a self-sealing polymer for aerospace applications. This material seals punctures in seconds, demonstrating its life-saving potential in spacecraft or aircraft windows.

Other plastics exhibit even more curious transformative characteristics. Liquid crystal elastomers (LCEs), developed at Rice University, stiffen when compressed rather than weakening—a counterintuitive behavior ideal for applications like tissue scaffolding or load-bearing structures. Harvard’s Wyss Institute has created tunable polymers that alter their surface properties—switching from hydrophobic to hydrophilic and from smooth to rough—based on simple deformations. These materials are poised to transform fields ranging from smart textiles to responsive building skins.

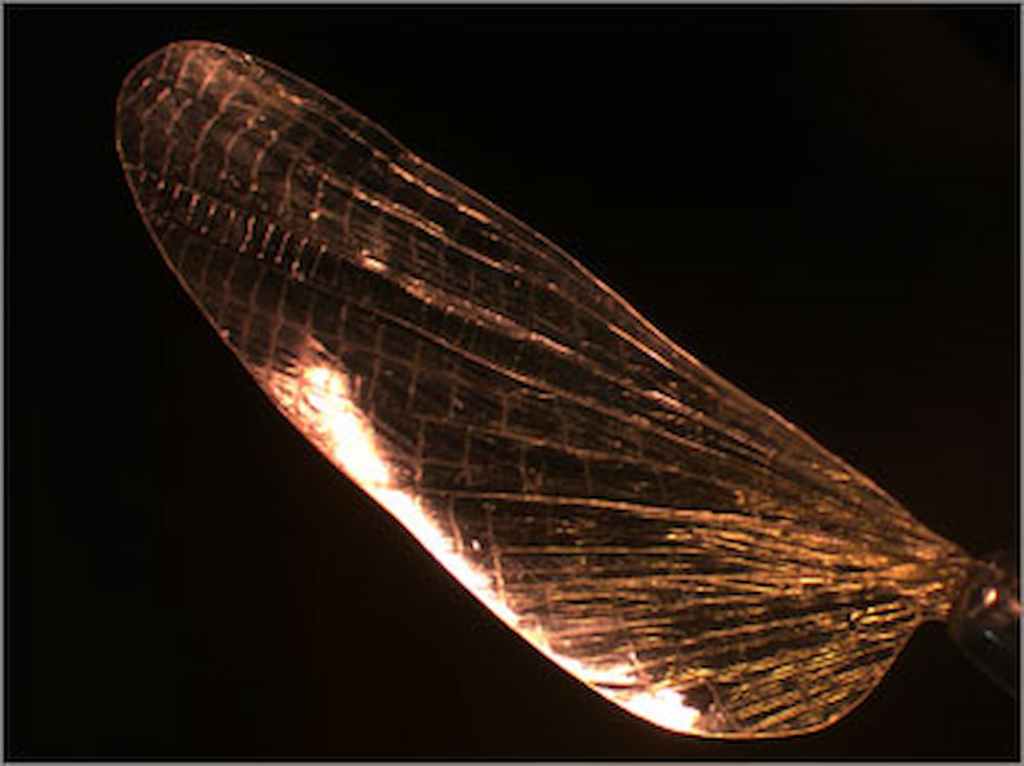

Light-responsive plastics further expand this repertoire. Architect Peter Yeadon’s photoluminescent bioplastics, for example, capture and emit light to enhance nocturnal navigation. Meanwhile, programmable e-ink polymers, like those used in large-scale wall displays, offer dynamic, energy-efficient ways to transform architectural surfaces into visual communication tools.

Yet plastic’s technological ambitions come at a cost. The material’s production heavily depends on fossil fuels, accounting for significant carbon emissions. Accidents like the 2023 East Palestine train derailment, which released vinyl chloride used in PVC, underscore the dangers of plastic’s toxic origins. And while we marvel at plastic’s utility, its proliferation has made it inescapable. Microplastics are now airborne, with studies revealing that cities like Auckland experience the equivalent of millions of plastic bottles descending as dust each year. These tiny particles invade ecosystems and human bodies, posing unknown long-term risks.

Despite growing awareness of these harms, the global demand for plastic continues to rise. The petrochemical sector now drives oil demand more than transportation, and plastic production is expected to account for nearly half of fossil fuel growth by 2050. This trajectory underscores the urgency of rethinking plastic’s role in society.

Fortunately, promising solutions are emerging. Bioplastics, for example, offer alternatives to traditional petrochemical plastics. Zeoform, made from cellulose and water, provides a biodegradable option for applications ranging from furniture to construction. Researchers at the Wyss Institute have also developed chitosan-based plastics derived from shrimp shells, which are lightweight, strong, and biodegradable.

Biocomposites are transforming building envelopes in architecture. The European Commission’s BioBuild project created facade panels from natural fibers and bio-polyester, cutting embodied energy in half compared to conventional systems. Meanwhile, companies like Newlight Technologies use greenhouse gases as feedstock, producing carbon-negative plastics like AirCarbon that sequester CO₂ during manufacturing.

Recycling innovations are also gaining momentum. The Good Plastic Company, for instance, repurposes polystyrene waste into durable architectural panels, while ByFusion’s compact machines convert mixed plastic trash into building blocks for walls and landscaping. These second-life strategies divert plastic from landfills and provide tangible solutions to the global waste crisis.

Plastic’s evolution mirrors humanity’s aspirations for innovation and convenience—but it must also reflect our commitment to sustainability. The next generation of polymers should not only mimic life’s resilience and adaptability but also its capacity for regeneration. This means designing materials with their entire lifecycle in mind, from renewable feedstocks to safe disposal.

Plastic can still fulfill its original promise as a revolutionary material—but only if it aligns with ecological systems rather than disrupting them. By steering its development toward biocompatibility and circularity, we can transform plastic into a tool for progress that supports, rather than endangers, planetary life.