It is rare and wonderful for people and ideas to come together at one time and one place. Lars Lerup (1940-2025), who passed away on November 5th, made that happen wherever he was, but especially for a few years at Rice University in Houston.

Of course, he did many other things, including being a very good architect and an even better storyteller about architecture, and he also was part of an amazing group of people at the University of California at Berkeley, but what he did at Rice in the early 1990s was extraordinary.

Building a Culture of Architectural Experimentation at Rice

He was lucky enough to find himself running a program that was small enough to be coherent, selective enough to attract bright minds, and rich enough to support experimentation as well as the logistics of bringing people together.

He had the vision and the persuasive power to put together a group that included at its core Michael Bell, Albert Pope, Carlos Jimenez, and Sanford Kwinter (in my opinion), but also extended to a changing cast of faculty members, lecturers, visitors (including myself; he let me run studios there twice). He solidified the ideas with debates, discussions, and publications, but also just through the chance encounters the presence of these people made possible.

From “Stim & Dross” to a New Way of Seeing the City

At the center of Lerup’s thinking was “stim and dross,” a phrase he coined and which was, as he himself admitted (according to a recent conversation I had with Bell) the best idea he had.

Dross was the miasma of both humanmade and natural sprawl that spread out from his perch in a high-rise tower near the Rice campus, encompassing the storm clouds moving in from the Gulf of Mexico, the tree canopy of live oaks obscuring the grid of streets below, the ticky-tacky boxes fit below them and emerging into merciless sunlight beyond the rich areas to become the continuous movement of Houston away from itself into the great planes.

Stims where the moments of stimulation: his own school, designed by James Stirling; the cocktails parties at the houses of rich donors he described with wry humor; highlights such as the De Menil Collection; but also the restaurants in strip malls serving the fiery food of whatever was the home province of one of the many ethnic groups that, like him, had migrated to that pulsing mass of energy that was Houston.

The Lerupian Lens: Surrealism, Subjectivity, and Scale

The essay was analytic and personal at the same time, which was the Lerupian mode. It started with him standing in “Houston, 28th Floor, At the Window”: “The sky is as dark as the ground; the stars, piercingly bright, a million astral specks that have fallen onto the city. On this light-studded scrim the stationary lights appear confident, the moving ones, like tracer bullets, utterly determined, while the pervasive blackness throws everything else into oblivion. The city a giant switchboard, its million points switched either on or off.”

He mused for a while about Duchamp and then returned to the view: “Back at my window, the palimpsest of a new city flaunts its hypertextuality in black and light; its mental map of diverse subjectivities rarely operates while one is on foot, a predicament that hints at the possibility of a new visibility, a new field with emergent, unexpected megashapes newly apprehensible but only at vastly different scales of motion… On the one hand, we have the Zoohemic Canopy constituted by a myriad of trees of varying species, size, and maturity and, on the other, we have a Downtown formed by the tight assembly of skyscrapers.”

The Architecture of Parties and the Materiality of Stimulation

This was, he said, “a city on the run from itself,” always moving out into the prairie in sprawl. If it had a substance, it was made up as much of the “assemblage” of “tree trunk/canopy and skyscraper/cloud cover” as it was of forgettable individual buildings. “The new space emerging from the impulses of this huge envelope is transient, fleeting, temporary, and biomorphic…barely visible to the classical eye…”

Designing a Domestic Theater of Disruption

Navigating through this dross, he goes to a party, where he arrives at a stim: “A colleague invites us to a reception given by an art patron. We traverse the plane and navigate the dross: A mental map, an address, a curving road, large lots and gigantic houses, the de rigeur smiling rent-a-cop. Our destination is a marvel of a house, a fantasy sustained by a spectacular architectural scenography, various addenda (arresting decoration, whimsical furniture, subdued music, etc.), and the glamour of the party itself. Truly stimulating. The collusion is in fact a perfect one, between architects (the curved interior street), decorators (the towels arranged on the floor in the bathroom), caterers (the glutinous loot of shrimp), the art patron (her son’s taxidermic hunting trophies) and her own overflowing enthusiasm. Suspended, the audience hovers in the fantasy. The house itself is a miniaturized Siena, (turning abruptly I search for a glimpse of the Palio), though not Siena at all, a marvelous polyphonic concoction that threatens all analogy in favor of the authenticity of the bristling Stim itself. Here critique and skepticism must fade in favor of the materiality of this specific event.”

He believed that it was the multi-layered evocation native to both his writing and his design that made this text so compelling. It also provided an understanding of the relation between these two poles or experiences –or just views of the semi-detached observer– that could help us move beyond the debates between New Urbanists, who had a strong foothold at Rice, and deconstructivists; between planners and architects; and between Postmodernists of any color. It was by looking at the three-dimensional and ever-changing landscape that we were continuing to remake that we could figure out how to act as architects.

Within that sprawl, you had to make yourself at home, and Lars Lerup cared about being at home. A wanderer exiled from his native Sweden as a student and moving from one academic position to another, he wanted to belong and concentrated his design efforts on creating the objects that would allow him to be there.

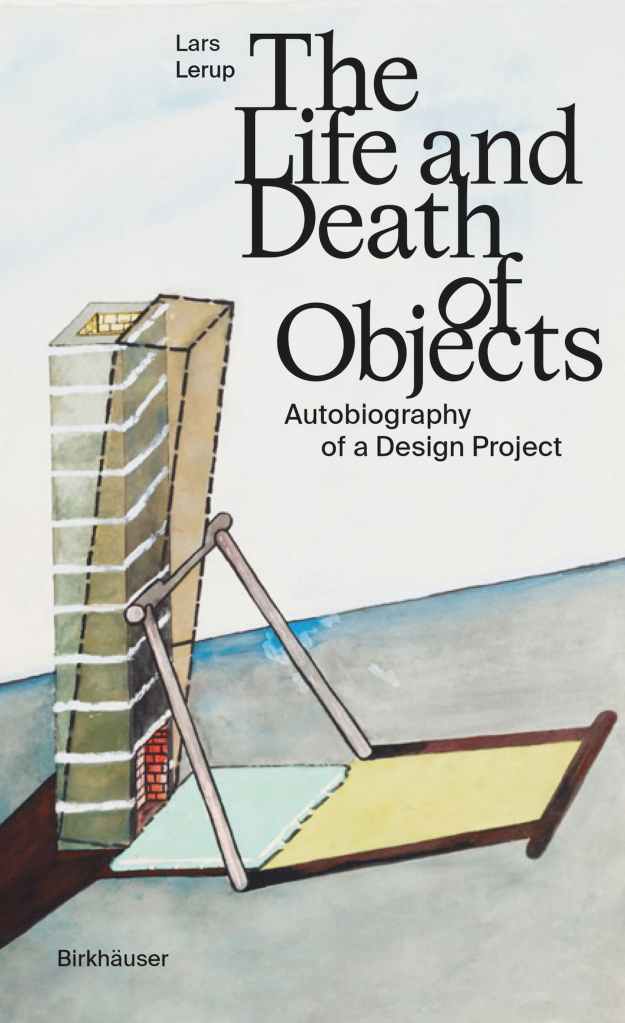

They were not houses, because he usually lived in apartments, but furniture. These armoires, beds, and chests of drawers were also beasts and interlocutors that questioned the spaces and the users. Lerup gave them personalities and stories.

There was a table made from a surfboard, supported by a bowling ball, and an armoire that was off-kilter, as if it had been rescued from a junkyard and fixed up. Some of the furniture invited or even demanded your action: you had to kick the door of the armoire to get it to open, and a chair left you off-balance.

Lerup presented these works as a kind of musing about form, the body, and space that married the memory memes of Aldo Rossi, the masque’d characters of John Hejduk, and the evocative minimalism of an Ingrid Bergman film.

What animated these pieces, as well as his architecture (little of which was ever built, unfortunately) was his brand of dark Swedish humor that could be both bawdy and tender at the same time.

Humor, Memory, and the Questioning Object

In a book published a few years ago, Lerup referred to these as “disloyal objects…that question predetermined stations in domestic space…and roles in the grammar of plans.” That was a description of his work in general: rather than responding to rules and regulations, it opened them with humor rather than theoretical counterpropositions.

The alternatives to a domesticity that confirmed gender roles or hierarchies was in objects, whether they were notional furniture or buildings, that offered resistance and strangeness, contradictions and enigmas, but always with a great deal of wit.

A Master Educator and Global Instigator

Being with Lars Lerup or his objects was fun, but also sometimes irritating and intimidating. He talked a lot, did not suffer fools, and was not shy to dominate a room. But he was also one of the best teachers I have ever seen at work, coaxing work out of students they did not know they were of capable of and making them members of a loose confederation of Lerupians that spanned the globe. That coterie also included faculty members who worked with and for him, collaborators and even the kinds of frenemies he loved to cultivate.

Beyond Theories: Lerup’s Network of Ideas

Lars Lerup never became a starchitect and never developed an overall theoretical framework. Instead, he worked in apercus and intimations, objects and exquisite drawings that always seemed to be a mixture of analysis, spec, and evocative image, animated by a certain yearning for a remembered, simpler Sweden.

Above all else, he was a social agent, finding connections and critical vectors that sped not only through architecture, but also into art, biology, and any number of other fields. I will miss his insights, his humor, and that continual, slightly cynical, slightly romantic and nostalgic perception of a world that needed design intervention.