For generations, Frank Lloyd Wright’s reputation has rested on his sweeping architectural achievements: the Prairie houses, Fallingwater, the Guggenheim. But a new exhibition argues that the story of Wright’s modernism cannot be told without his furniture—especially his chairs.

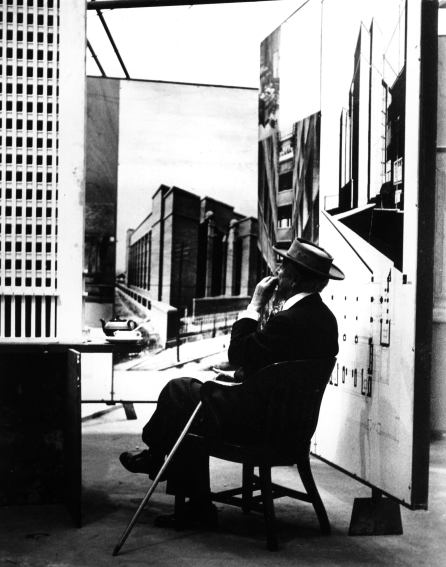

This fall, the Museum of Wisconsin Art (MOWA) in West Bend presents Frank Lloyd Wright: Modern Chair Design (Oct. 4, 2025–Jan. 25, 2026), the first exhibition to reframe Wright’s furniture as central—not secondary—to his architectural vision. Featuring more than 40 chairs, many on view for the first time, along with sketches, photographs, animated renderings, and newly constructed works, the exhibition invites architects and designers to see Wright not only as an architect of space, but as an architect of the human body at rest.

“Wright believed that a chair was never just a chair—it was a living design, inseparable from the environment in which it sat,” says Thomas Szolwinski, MOWA’s Associate Curator of Architecture and Design.

Furniture as Architectural Experiment

The exhibition is based on new research by architectural historian Eric Vogel, scholar-in-residence at the Taliesin Institute. Vogel’s archival deep dive revealed connections that challenge the prevailing perception that Wright’s furniture was an afterthought.

“When Wright rebuilt Taliesin after two major fires, he paired the new architecture with significant new and unprecedented furniture forms that were rejected by his clients at the time for their unconventionality,” Vogel explains.

Five Eras of Innovation

Best known as a leader of the Prairie School movement, Wright designed more than 200 unique chairs over his lifetime, most of them little studied. Modern Chair Design shines light on his post-Prairie School years, tracing five distinct design periods between 1911 and 1959. The exhibition demonstrates how the designs emerging from Taliesin East in Wisconsin and Taliesin West in Arizona reflected larger evolutions in his architecture—from Prairie horizontality to the spiraling dynamism of the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

One striking curatorial highlight is the first-ever construction of chairs Wright designed for the Guggenheim café, long considered unbuildable. Other re-creations, produced with the help of renowned woodworkers—including Wright’s great-grandson, S. Lloyd Natof—allow visitors to experience Wright’s bold, often angular seating in three dimensions for the first time.

Contextualizing Wright in Modernism

The exhibition situates Wright’s furniture within the broader currents of design history and American modernism. Unlike contemporaries such as Mies van der Rohe or Marcel Breuer, whose tubular steel chairs embodied machine-age efficiency, Wright’s furniture insisted on craft, warmth, and materiality. His chairs were not conceived as standalone products but as integral components of a spatial ecosystem—extensions of hearths, dining rooms, and communal life.

Why Wright’s Chairs Matter Now

As contemporary architects grapple with holistic design and the blurred boundaries between architecture, interiors, and product design, Wright’s conviction that “the chair is the most difficult thing to design” underscores his belief in total design. For him, a chair was never simply furniture—it was architecture, distilled.