At first, the number at the lower left corner of the small drawing seems to be a trace of curatorial cataloging: 01.01.87. But then it reveals itself to be a date: Jan. 1, 1887, written in the architect’s own hand: a Saturday, on which day he was all of 19 years and six months old. “First Drawing,” he’s written above the numbers. Faint graphite on tracing paper, it’s a delicate and leafy elevation of an odd house that the actual curatorial catalog, in the form of adjacent wall text, normalizes as Victorian Queen Anne: narrow windows aligned in strips, a low conical turret, a front door engraved in a broad semicircular Richardsonian Romanesque arch. But there are other annotations in the same handwriting. “Dream House,” says one in red pencil. And another, more prosaically: “Study made in Madison previous to going to Chicago.” And another, crossed out and half-erased: “Project. Cooper House, La Grange, Ill.” And then, boldly overwriting the lightly penciled and presumably earlier notations: “Drawing shown to lieber meister when applying for a job.” Here, at last, is the legend: Here—maybe—is the very drawing that got the teenager the internship that turned him, over the subsequent five years in which worked as a draftsman for Louis Sullivan, into Frank Lloyd Wright.

The First Drawing

The First Drawing is the very first drawing you see, just inside the entry, in the exhibition “Frank Lloyd Wright at 150: Unpacking the Archive,” which runs until Oct. 1 at New York’s Museum of Modern Art. In one of architectural scholarship’s better ironies—given the famous mutual slighting and snubbing between Wright and Philip Johnson over Johnson and Henry-Russell Hitchcock’s canonical International Style exhibition at MoMA in 1932—the museum, in partnership with the Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library at Columbia University, acquired in 2012 the vast archive of Wright’s seven-decade career that had been assembled by the Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives. As curator Barry Bergdoll explains in the show’s introductory text, “ ‘Unpacking the Archive’ refers to the monumental task of moving across the country 55,000 drawings, 300,000 sheets of correspondence, 125,000 photographs, and 2,700 manuscripts, as well as models, films, and building fragments” representing 1,000 building designs and 500 built works.

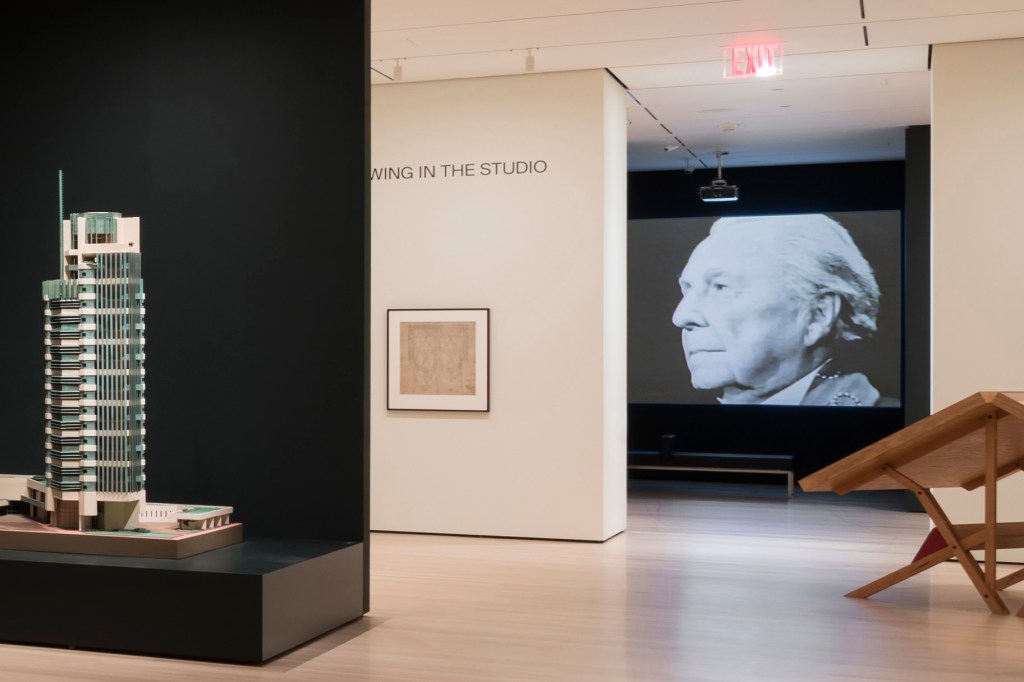

Jonathan Muzikar/The Museum of Modern Art

A view of the exhibition

Jonathan Muzikar/The Museum of Modern Art

Exhibition view

The Effort Behind the Effortless

A trove of such abundance and variety invites two approaches. The first is a kind of big-data grind: a tenacious and comprehensive project of excavation and pattern-recognition. This is the work of Avery Library curator Janet Parks, whose endeavors are highlighted in the exhibition’s central gallery display, Drawing in the Studio. Parks sorts through the drawings produced by Wright’s various ateliers, identifying not only the role of his hand in the workflow but also the distinguishing the handwriting and handiwork of generations of draftspeople—Marion Mahony Griffin above all—who constructed the Wright aesthetic. “There’s close to half a million of pieces of paper,” Parks observes in a short film accompanying the drawings on display, and yet the encounter with each piece of paper is intricate and intimate—a glimpse into the effort behind the seemingly effortless. “He’s reworked it so often,” Parks notes of one drawing, “that there’s a cutout in the middle.” “He’s such a larger-than-life figure,” she reflects, “that you kind of expect these vast drawings. But in fact he’s quite delicate, working his way through the details. His handwriting is small.”

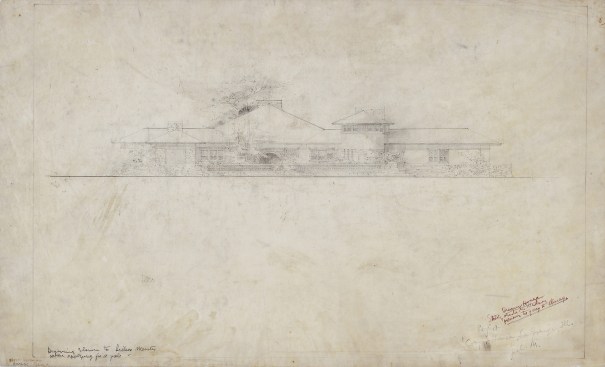

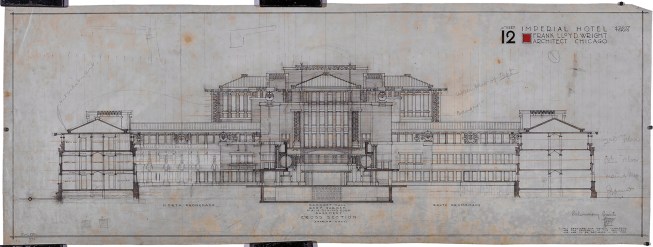

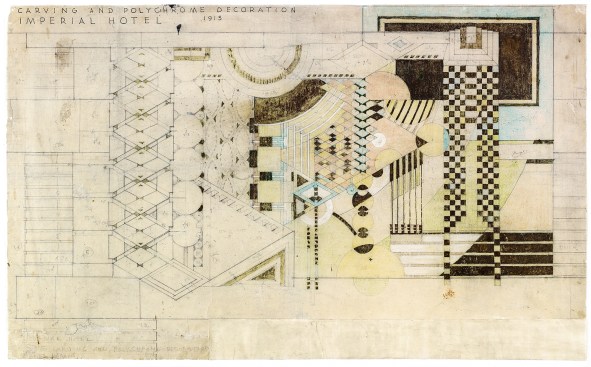

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University, New York)

A cross section of Wright's Imperial Hotel in Tokyo (1913–23)

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library

Wright's Imperial Hotel in Tokyo (1913–23)

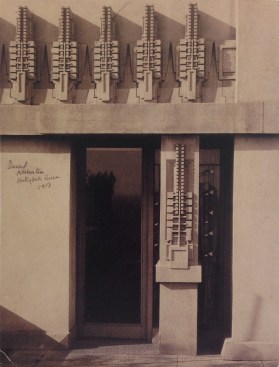

The second approach to such an abundant archive is to go narrow but deep: to drill down into the far corners and under-reported stories to which all that paper gives new articulation. This is the approach taken in the thematic galleries, which are arranged around the central drawing display, and each of which highlight key documents and ideas identified by different scholars—each of whom, like Parks, are featured in looping films. It’s touching to see and hear their energy and rigor. Architectural historian Ken Tadashi Oshima studied 800 drawings and documents around Wright’s long-since-demolished Imperial Hotel in Tokyo, which opened in 1923. “One of the great finds was this book from 1924 that I had never seen before,” he says, referring to Teikoku Hoteru, an illustrated photographic compendium of the hotel. The book was the only form in which Wright ever saw the finished building—and on which he kept reworking it, penciling over the illustrations, refining the landscaping and details. A conventional interpretation of the hotel is as a prodigious synthesis of Orient and Occident, assimilating Wright’s early fascination for traditional Japanese prints with a latently Neoclassical and symmetrical master plan. But Oshima repositions the work, pointing to a single sentence in the book that asserts the building is not a synthesis of sources, but, “Neither East nor West,” a unique artifact somehow suspended between global cultures. “That’s part of the reframing,” he observes, that the archive enables.

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library

A portrait of Wright by an unknown photographer

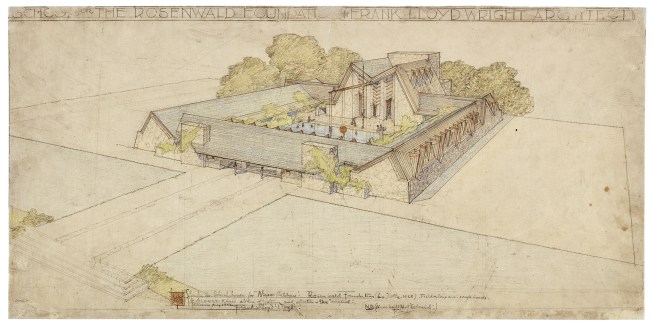

Problematic paradoxes and hidden histories abound. Mabel Wilson, an associate professor at Columbia’s Graduate School of Architecture, Planning and Preservation, identifies an unbuilt project that, as she observes in her filmed commentary, “doesn’t have a big footprint in the archive” but that carries significant historical weight: Wright’s little-known 1928 redesign of the standard Rosenwald School building, part of a subsidized but segregated school-construction program for African-American students that was undertaken across the South in the first few decades of the 20th century by Sears, Roebuck & Co. chairman Julius Rosenwald. Wright enriched the dourly spartan schoolhouse template with a gracious patio and pool. Wilson notes that, “he was willing to adapt those ideas,” from rarefied prior projects to a very different context. And yet, she observes, Wright’s correspondence characterizes all African-Americans, not just schoolchildren, “as being childlike. There’s a sensibility of the cultural hierarchies of that time.”

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library

Wright's Rosenwald Foundation School for Hampton Normal and Agricultural Institute in Virginia (1928)

In another gallery, landscape architectural historian Therese O’Malley takes on a dilemma hiding in plain sight: Wright’s stylized plant motifs, which in received wisdom are evocations of the American prairie. But, “looking at the hollyhock,” she notes, “it was actually naturalized at this kind of imperialistic moment when we wanted to bring them in,” importing them from their native habitats in Europe and Asia—prompting O’Malley to ask, “What is an American garden?” Adds MoMA researcher Jennifer Gray, “it’s also about social ecologies and political ecologies. All of these natures are very constructed.”

The Frank Lloyd Wright Foundation Archives (The Museum of Modern Art | Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library

A detail from the terrace of Hollyhock House

The Emergence of Architectural Historiography

It’s tempting, in our age of hacked email dumps and fake news, to look for stable truths in primary sources like the Wright archive. But what makes documents like the First Drawing so compelling is not that any of Wright’s annotations—Dream House; Study; Project; Cooper House—might be the definitive one, but that all of the drawing’s sequential or simultaneous identities may be differently true. This polysemous possibility is the great advantage of considering any one piece of paper not in isolation, but as part of a pattern of a half-million such pieces that might be placed next to it. For all the paper that architects, even now, produce, architectural historiography—the interpretation of documents and records—still feels like an emerging field. While fully sounding the depths of the archive will take years, the breadth, variety, and scholarly chorus of “Unpacking the Archive” enables us to see the work of Wright—who as early as 1932 was already the ubiquitous, prodigious, overfamiliar, cliché-adjacent Frank Lloyd Wright—as if for the first time.