Making it hyper-real and making it unreal seem to me to be among the best ways to approach architecture these days. At the closing events for the 2015 Shenzhen-Hong Kong Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism and Architecture (UABB), which I co-curated this winter, we heard from two practices that represent these extremes with verve: FieldOffice Architects (not to be confused with James Corner’s Field Operations) from Taiwan and WAI Think Tank from Beijing. While FieldOffice has dedicated itself to small, community-based projects mostly concentrated in one small city on Taiwan’s eastern coast, WAI Think Tank—the result of a global collaboration between French Nathalie Frankowski and Puerto Rican Cruz García, who met in Brussels before moving to Beijing—produces some of the most astonishing visions and seductive stories about architecture I have heard since Delirious New York came out almost 30 years ago.

Courtesy Field Office

Cherry Orchard Cemetery Service Center

Yale-educated, Eric Owen Moss Architects alumnus Sheng-Yuan Huang started FieldOffice Architects 13 years ago when he moved back to Taiwan. Rather than returning to his native Taipei, he settled across the coastal mountains in Yilan City. An agricultural and fishing community, Yilan fills the plains between the hills and the ocean with a dense mixture of urban and rural patters. Huang began working with local residents to propose such projects as a pedestrian bridge that acts as a “parasite” on a highway overpass, a riverfront park, a renovation of an old factory into a community center, and a canopy that shades a space for outdoor gatherings of all sorts. By outlasting politicians and building incrementally, he was able to realize a remarkable amount of these bits of “urban acupuncture,” as he calls the works.

Courtesy Field Office

Cherry Orchard Cemetery Service Center

In recent years, Huang has also designed larger projects, including the Cherry Orchard Cemetery Service Center, whose voluptuousness both belies our associations with death and turns it into an elaboration of its natural setting. What is just as remarkable as the nature of the work is how he produces it: Working from a small house on the rural fringes, he told the UABB’s closing ceremony overflow crowd (students seem to have cottoned on to his work rather strongly in China), he has breakfast and meditates in the fields every morning before going to the office a few hours away “when they need me.” There, he not only works, but also dines and watches movies with the apprentices and associates who live communally in one building.

Courtesy Field Office

Dakeng Pump Station

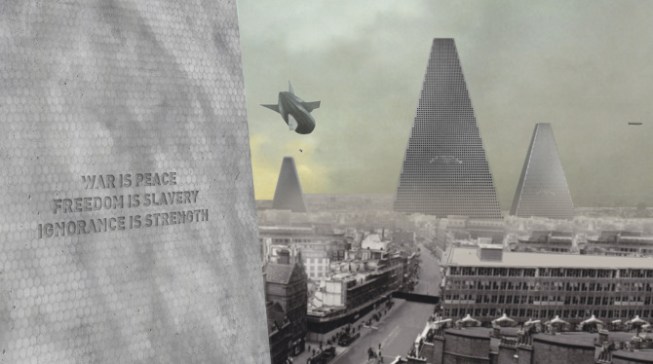

García and Frankowski have something very different in mind with WAI Think Tank. They make what they call narrative architecture: “Its colossal monuments, impossible landscapes, and allegoric texts are real depictions mirroring the absurd scenarios … architecture as an endless supermarket…” Starting with a manifesto they wrote in 2008, they have been assiduously collaging together fragments from some of architecture’s most famous utopias, ranging from Superstudio’s grids steamrollering over Manhattan to the constructivist dreams of buildings like clouds.

Courtesy WAI Think Tank

The Tourist, a short story by WAI Think Tank

They also invent their own forms, both in drawings and words. The Tourist, a story of a former lover summoned by his ex to a place that looks a lot like Beijing, who founds himself lost in its many labyrinths, from the gates at the airport, “an endless network of corridors and travelators all linking to each other in a continuous loop to the grid of the city itself.” Then he follows the sense of an apparition, where the story ends:

And rising above some small shops, he could spot it, right in front of him. A huge concrete mass emerging from the compact pattern of the alley, revealing an orthogonal and unornamented shape. Apart from its sheer size, its featureless façade made it hard to blend with its environment while at the same time making it strangely easy to remain unnoticed by the rest of the city. He stared at it like he was experiencing an urban mirage, a dream within the city. Was this what he came looking for? He gazed at the shape in front of him, unable to move or to think.

Courtesy WAI Think Tank

Stills from Blindness, the second installment of a three-part architectural narrative.

In projects such as Blindness, WAI (an acronym for a rhetorical question posed by the firm: What About It?) seems to be evoking a nihilism that is the final result of staring too long at the visions modernists dreamed up. But WAI always pulls back, acknowledging the role of humor and play in its work. To the pair, the ruins of modernism’s ambitions are toy blocks from which they can erect other possible futures.

When García and Frankowski translate their own visions into proposals for buildings, however, the work becomes more generic. I hope that, at least for now, they stick to developing their mythical world with as much dedication as Huang has spent on his incremental additions in a small coastal town in a place far, far away. For that is what the work has in common, strangely enough: the pursuit of architecture as a myth; not a fiction, not a function-driven bit of technology, but the evocation and emplacement of another world within our own reality, however elusive that real world might be.

Courtesy WAI Think Tank

Stills from Blindness, the second installment of a three-part architectural narrative.

Watch “Blindness,” the second installment of a three-part series of architectural narratives developed by WAI Think Tank, below: