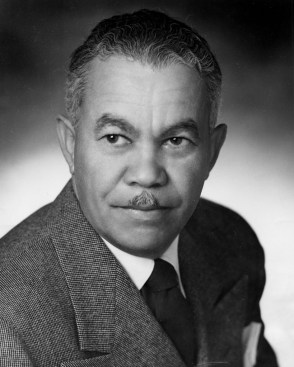

courtesy Herald-Examiner Collection/Los Angeles Public Library

Paul Revere Williams in 1951

Paul Revere Williams, FAIA was the first Black architect to become a member of The American Institute of Architects in 1923. And in 2017, he became the first Black winner of the AIA Gold Medal more than 35 years after his death in 1980.

Throughout his career, he designed several high-profile projects in Los Angeles, including the Music Corporation of America headquarters in 1939; the Los Angeles County Courthouse in 1951; Los Angeles International Airport in 1960; UCLA Pritzker Hall in 1967; and renovation work on the Beverly Hills Hotel from the 1940s to the 1970s. Williams’ affinity for Modernist style became his signature, which helped define LA’s architectural lexicon. And while the architect has been celebrated for his iconic works in Southern California, his projects in Nevada have not garnered as much attention. Williams helped develop the state’s built environment with private residences, apartment buildings, public housing, and a church.

Janna Ireland

Paul Revere Williams’ La Concha Motel, Las Vegas, Nevada, 1961, 2022, chromogenic print.

In an exhibition organized by the Nevada Museum of Art, photographs of Williams’ design contributions to the state—from the 1930s to the 1970s—will now be on view at the Center for Architecture in New York from July 13 to Oct. 31. Janna Ireland on the Architectural Legacy of Paul Revere Williams in Nevada sees contemporary artist Janna Ireland share her journey photographing and sharing the architect’s Southern California work starting in 2016. From there, Ireland became fascinated with his work and historical significance, going on to show her architectural photographs of Williams’ designs in 2017 at the WUHO Gallery in Los Angeles. In 2020, she released her book Regarding Paul R. Williams by Angel City Press.

Janna Ireland

Janna Ireland's book Regarding Paul R. Williams published by Angel City Press in 2020.

The 34 photographs that will be displayed are a direct result of her winning the Peter E. Pool Research Fellowship in 2021, which allowed her to travel to Nevada to capture Williams’s designs on film. Ireland walks ARCHITECT through how the exhibition provides a glimpse into some of Williams’ noteworthy work in Nevada. The following interview has been lightly edited for clarity.

Janna Ireland

What got you interested in photographing Paul Revere Williams’ work?

I started photographing his structures in Southern California in 2016. And that was because one of my former professors passed my name along to Barbara Bestor who is an LA-based architect and director of the Julius Shulman Institute at Woodbury University, a space dedicated to architectural photography. She realized no one had done a project about Williams and he wasn’t really being talked about. And then it continued from there. I had my exhibition [There is Only One Paul R. Williams at the WUHO Gallery in LA] that Barbara set up, then I kept [photographing Williams’ work], which led to my book [Regarding Paul R. Williams] and a fellowship opportunity with the Nevada Museum of Art. Almost all of the work in the show is a result of that fellowship.

What are some things you learned about Williams from your journey photographing his work from 2016 to now?

I learned that he had an incredible set of skills as an architect—including drawing, which he was known for as a child—to things like his business skills and the way he was able to set up and maintain a career for himself. I would describe him as tenacious, but not in the way we think of someone being tenacious today because the social rules are so different.

How did you go about completing this exhibition at the Nevada Museum of Art? What was the process like?

This part of the overarching project on Williams was much easier for me than the Southern California part—despite all of the travel—because in Southern California I was doing research, reaching out to people, getting in touch with real estate agents about listed houses, and trying to put everything together. But when it came to this show, the Nevada Museum of Art and Carmen Beals, the curator of the exhibition, were doing a lot of that legwork. I had so much help.

Janna Ireland

Paul Revere Williams’ El Reno Apartments, Reno, Nevada, 1937, 2021, chromogenic print.

Why do you think it’s important to showcase Williams’ Nevada architecture?

He’s mostly known for his work in Southern California. And that’s becoming increasingly well-known today. Although, he was well-known during his lifetime. Then there was a period after his death when people—outside of those really interested in architecture in LA—weren’t widely aware of his work.

However, finding out that he had done all of this other work in Nevada and had such a significant relationship with the state was really interesting. I think it just adds another layer of information for people who know his work and know about him, while also hopefully introducing his work to people in Nevada.

Janna Ireland

Paul Revere Williams’ Guardian Angel Cathedral, Las Vegas, Nevada, 1963, 2021, chromogenic print.

Which of his Nevada projects stuck out to you most?

The one that always comes to mind is the Guardian Angel Cathedral in Las Vegas. I photographed this one before I got the fellowship at the Nevada Museum of Art. I visited Nevada and photographed a few buildings, including the Cathedral, which led to Carmen finding me and getting the fellowship.

Why do you think this exhibition is important for the architecture field?

Well, I think that it’s important to consider the history of architecture and consider who was making decisions about what was important. The fact that Williams was the first Black member of AIA in the 1920s and then only became the first Black AIA Gold Medal winner in 2017. I don’t want to describe the exhibition as corrective; it’s not. It’s not changing anything that happened. But, I hope that it makes some people consider the fact that a lot of interesting and important work was being done by architects who were not white men.