Charlie Brown

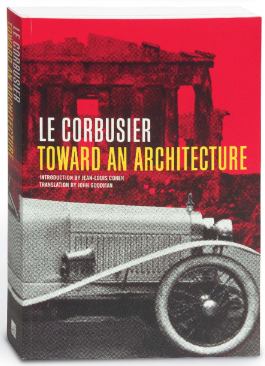

Toward an Architecture By Le Corbusier Introduction by Jean-Lo…

From a scholarly standpoint, it is surely beneficial to have a more precise translation than the one we English speakers have lived with all these years. However, when it comes to rhetorical prose bordering on the poetic, a literal translation is not invariably desirable, particularly given the fact that no text can be translated literally all the time without losing the rhetorical rhythm of the original. Hence, in my view, it is not always clear which version is preferable.

By way of example, a certain doubt arises with Goodman’s rendering of a famous passage, which in Etchells’ translation reads:

Goodman does little to emend this, except, inexplicably, to omit the “and” that is present in both the French and in Etchells’ translation and to render “c’est beau” in the flat form of “it is beautiful,” and finally to translate strictly Le Corbusier’s “L’art est ici” as “Art is present.” In my view, Etchells’ “Art enters in” captures more successfully the lyricism of the original French. What Etchells instinctively understood, and what Goodman seems all too perversely to resist, is the inherent elision of the French language, which must be acknowledged analogically to some extent in any translation of a poetic text: So Etchells’ coinage of the expression “Engineers’ Aesthetic” is surely preferably to the literal translation, “The Aesthetic of the Engineer.” Thus the rigor of this retranslation results, here and there, in a regrettable flattening of the evocative language to be found in the original.

As in all translations, there is no final answer to such aporia, except that one should be as sensitive as possible to the overall cultural context in which the work appears. Here, one has to say—notwithstanding his inexcusable liberties—Etchells may not have always been so wide of the mark. For in the end, as Reyner Banham observed in his perceptive and grandiloquent Theory and Design in the First Machine Age:

While Banham could not critically dispose of the compelling metaphorical links between Le Corbusier’s various segments, he was correct in stressing the persuasively poetic character of the writing. It is this, plus the brilliant, often disjunctive combination of modern mechanical paradigms with ancient classical references, that would in the end carry the day. So much so that it would serve, paradoxically, both to undermine the credibility of the European academic legacy and to determine the vocation of young architects all over the world for the best part of the 20th century.