In a light-filled, one-room architecture studio in Brooklyn’s DUMBO neighborhood, Anne Marie Lubrano, AIA, is talking Camelot. When the small firm she founded with Lea Ciavarra, AIA, began working on the project that would transform Eero Saarinen’s beloved but long-vacant 1962 TWA Flight Center into a hotel and conference center, it was 2014. The Obama family was in the White House and there was a sense of optimism that Lubrano thought must have been akin to the way the country felt when the Kennedys were in residence.

The revival of the TWA terminal, constructed at Idlewild (now John F. Kennedy) Airport in Queens when air travel was still stylish and commercial jets were much smaller—a hundred passengers on average—is clearly an attempt to monetize the joie de vivre of the early jet age. As hotelier Tyler Morse, the CEO and managing partner of MCR Development, the company behind the project, told The New York Times: “Sixty-two was a special year: John Kennedy was president, John Glenn circled the Earth, the space race was on.” To Lubrano, born when Nixon was president, 2014 felt just as special. “I can remember meeting Tyler and just feeling like the city was still booming and there was this hope and aspiration.”

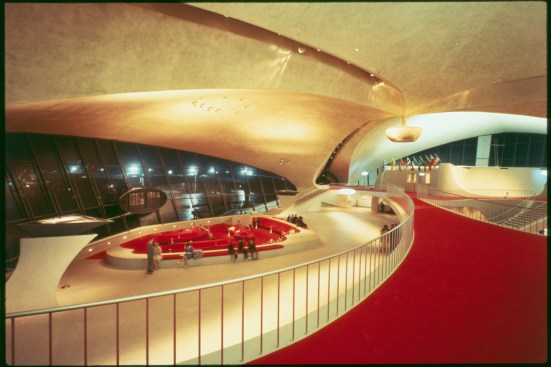

Balthazar Korab

The terminal’s sunken lounge circa 1962

David Mitchell courtesy TWA Hotel

The restored sunken lounge, with a new Solari flipboard

All that hope and aspiration culminated in mid-May with the reopening of the Flight Center, which had been mothballed after TWA went bankrupt for the final time in 2001. The historic terminal, restored by Beyer Blinder Belle (BBB), now serves as the entryway and lounge for a 512-room hotel designed by Lubrano Ciavarra Architects; a newly dug basement includes an additional 50,000-square-feet of event space.

The rebirth of Saarinen’s landmark, with its restored sunken lounge smothered in TWA red, its walls lined with vintage travel posters designed for the airline by artist David Klein, and its pay phones preserved and conspicuously positioned, can be seen an exercise in mid-20th-century nostalgia informed by 21st-century Instagram-driven placemaking. The opening day festivities featured a performance by a less-than-convincing group of Beatles impersonators singing on the mezzanine-level footbridge as young performers dressed as pilots and flight attendants shimmied. Meanwhile, dozens of actual TWA veterans once again circled the terminal, many wearing their old uniforms.

I spoke with two sisters, Marcia Bytnar-Rouse and Karen Bytnar, who had both worked as flight attendants in the 1960s and ’70s. They talked about how miraculous it seemed to come to work every day in this building (and then fly off to Paris or Rome). “It felt like we were in the future,” says Bytnar-Rouse. “Honestly, it still looks futuristic to me.”

David Mitchell courtesy TWA Hotel

A catwalk that runs above the sunken lounge and under restored skylights

A Starchitecture Trial Run

Except that future has moved on and gone places that neither Saarinen nor TWA anticipated. The Flight Center’s architecture is less visionary than quaint. It doesn’t speak of technological advancement but of craft; every oddly shaped opening and soft curve was handmade by contractors who were maestros of poured concrete. At night, when the whole curvaceous volume turns into a giant cocktail lounge, the shadows cast by all the convexities and concavities make it look like the set of a German expressionist film circa 1920.

The building represents an appealingly exotic vision of the past, one in which Idlewild decided that each major airline should have a symbolic stand-alone building, essentially giving the concept of starchitecture a trial run. Eero Saarinen, who escaped from the architectural shadow of his father, Eliel, when he won the 1948 competition for the St. Louis Gateway Arch, a great stainless steel wishbone that still looks structurally implausible, emerged in the 1950s as a progenitor of an unusually expressive architectural language. While some of his buildings were rectilinear to a fault—Bell Labs in Holmdel, N.J., comes to mind—many of them, like the Ingalls Rink at Yale University, with its curving concrete spine or Dulles International Airport outside Washington, D.C., with its ski jump roof, appeared to be equal parts liquid and solid.

David Mitchell courtesy TWA Hotel

The renovated Paris Cafe

David Mitchell courtesy TWA Hotel

The restored "Pope's Room" in the Ambassador Lounge

Every fluid new Saarinen design was an invention, untested and full of engineering and aesthetic challenges. None more so than TWA, which was completed a year after Saarinen died of a brain tumor. The building’s avian form, unlike, say Santiago Calatrava, FAIA’s bird-inspired World Trade Center Oculus in Manhattan, didn’t benefit from computer software that could calculate stresses or guide fabrication of components. The process of building the swooping concrete structure had to be improvised, Saarinen working in close collaboration with engineer Abba Tor of the firm Ammann & Whitney, and Grave Shepherd Wilson & Kruge, the contractor. To develop his unconventional concepts, Saarinen tried them on, fashioning huge models that he endlessly manipulated. A photo on the wall in one of the TWA Hotel’s exhibition areas shows Saarinen face-down inside a Flight Center model, only his legs sticking out the back.

Most astonishing was the terminal’s construction method. The August 1960 issue of Architectural Forum detailed how Saarinen’s firm went from its “rough working models” to something like construction documents. What the architects gave to the contractors were, in essence, topographic maps. “From these ‘contour maps’ the contractor had to develop still more elaborate drawings to show every rib and connection for the actual form work needed to hold up the concrete on the site,” the magazine reported.

A photo in Architectural Forum showing the pouring of the terminal’s roof

Photos that ran with the story captured the intricacy and the improvised nature of the formwork—an impossibly dense construct of plywood and scaffolding that resembled those early Zaha Hadid paintings, in which unlikely architectural objects are alluded to by blizzards of polygons flying in all directions. When the last of the formwork was stripped away in late 1960, the fact that the 5,500-ton structure remained standing, balanced atop four concrete buttresses, was a near miracle. And the fact that it still stands, balanced like a bird on “spindly little legs,” as Richard Southwick, FAIA, BBB’s director of historic preservation, puts it, is no less remarkable.

A Monument to Blissful Ignorance

You can view the Flight Center as a symbol of a time when air travel was exhilarating and stylish. Or a harbinger of the sort of architectural gymnastics we now take for granted. But you can also look at it as a symbol of confidence, a monument to the idea that we could will the world to behave in unprecedented new ways by relying on skilled know-how and audacious improvisation.

Yet the building can also be read as a monument to blissful ignorance or, perhaps, denial. One thing that Saarinen didn’t know was that airplanes were about to get much bigger. The Boeing 747, which could be configured to carry as many as 480 passengers, was under development in the 1960s and began commercial service in 1970. As the airplanes grew, Saarinen’s terminal began to feel smaller. According to Lubrano, it was designed for a capacity of just 600; later, “bat wings” were added on to the original bird to increase baggage storage capacity. Saarinen’s other 1960s airport, Dulles, was enlarged in 1996 by extruding his great swoop of a terminal to double its original size. But that solution wasn’t possible at TWA, a work of sculpture that simply couldn’t accommodate the rising passenger numbers or the security infrastructure required after September 11.

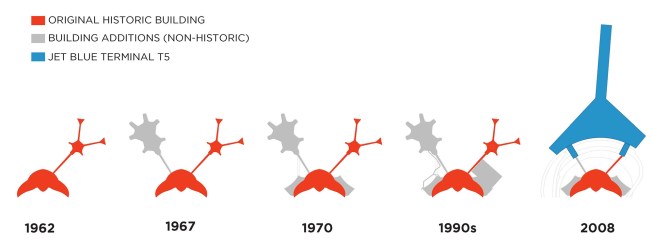

The new hotel wings help obscure the 2008 Jet Blue terminal that was constructed behind Saarinen's original structure

Lubrano Ciavarra Architects

TWA's site plan over the years

Southwick of BBB, a New York firm renowned for its restoration work on landmarks such as Grand Central Terminal and the Empire State Building, began his long engagement with the Flight Center in 1994, just after the building was designated a landmark by New York City. The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey, which owns and operates the metropolitan area’s airports, including JFK, has what’s called “superior jurisdiction,” meaning it could have ignored the landmark designation. “They wanted to know if they could tear it down,” Southwick recalls. “I said yes, but I wouldn’t want to be in your shoes.”

According to Southwick, there were a variety of plans for the site in the 1990s and 2000s, including a combined United Airlines/JetBlue terminal that could have incorporated Saarinen’s TWA. “Actually, a few days before September 11, there was a tour with Neil Levin,” Southwick told me. “There was going to be a big article the Sunday after, stating that the TWA terminal was being saved, and this would be the keystone of all the new structures around it.” Levin, the executive director of the Port Authority, was killed in the World Trade Center attack, and those plans never materialized.

In 2008, when I last saw Saarinen’s TWA, JetBlue was putting the finishing touches on a terminal that it was constructing directly behind the historic building. At some point I heard that the Flight Center might serve as a dedicated gateway to JetBlue: Cabs would drop passengers at TWA, they’d walk through an architectural wonderland, and then into JetBlue’s highly optimized environment. Southwick called it “a very romantic notion,” one that “made no sense at all.”

David Mitchell courtesy TWA Hotel

A restored flight tube, which connects to one of the hotel wings

David Mitchell courtesy TWA Hotel

Guests check in at the rebuilt terminal counters (left) and then take a procession of steps up to the main level

All along, the Port Authority had been searching for a development partner that could transform the Flight Center into a hotel. André Balazs, known for the Standard Hotels and Chateau Marmont, originally won the bid, but his business plan turned out to be impractically modest, and he pulled out. In 2014, Morse and MCR made their successful pitch, which hinged on having enough hotel rooms to make the project financially viable.

Lubrano’s design team was able to make space for the two new hotel wings by demolishing the various additions that had been made to the Flight Center over the years. The new wings curve subtly and act as a backdrop for the historic building, concealing what couldn’t be removed, including the JetBlue terminal. Inside the Flight Center, BBB attempted to re-create the experience of TWA circa 1962. “So we ended up doing all the glass. We did that sunken lounge. That was all plywood-ed over at one point,” Southwick told me. As for the passenger check-in area (now the hotel check-in), “we ended up reconstructing it entirely using old shop drawings.” A Queens-based upholsterer re-created the banquette seating, and a factory in China replaced millions of aspirin-sized Italian tiles. The Ambassador Lounge, the one dining area that was seamlessly designed by Saarinen (the other restaurants were farmed out to Raymond Loewy’s firm), with seating by Eames and a Noguchi fountain, was meticulously restored. The old terminal now looks conspicuously new.

David Mitchell courtesy TWA Hotel

The view of the runway from the infinity pool on the hotel roof

Some things are different, of course. An old baggage carousel space is now a ballroom. There’s a simulated tarmac outside the sunken lounge with a 1959 Lockheed Constellation airplane that’s been converted into a cocktail lounge. The famous tube-shaped passageways that used to lead from the central part of the terminal to the gates now take guests to the hotel wings. And there’s a heated pool and cocktail lounge on one hotel rooftop, overlooking a very busy runway and a natural gas-fueled power plant atop the other wing.

The hotel rooms themselves are 1960s-inspired and feature Saarinen-designed Tulip Tables and TWA-red Womb Chairs, and the kind of pole lamp that was so ubiquitous in the mid-20th century that even my unstylish parents owned one. Mike Suomi, Assoc. AIA, a principal and vice president of interior design at Stonehill Taylor in New York, the firm behind the design, said that the rooms are mostly intended for short-term guests who might be incapacitated by jet lag. “We wanted to create an oasis so that it took the traveler away from the hectic nature of air travel today, gave them a place to relax and unwind.”

David Mitchell courtesy TWA Hotel

David Mitchell courtesy TWA Hotel

A hotel room, complete with martini bar and Womb chair

A Bittersweet Fantasy

I’m thrilled the Flight Center was preserved and restored, and is once again full of life. I especially loved the view of Saarinen’s building that I got from my hotel room during my stay on opening night. My bed faced the window, which is 5 inches thick and blocks the airport noise. I peered out into the former Ambassador’s Club; the Noguchi fountain was about even with the foot of my bed. I saw the swoop of the great roof and everything around it. An elevated AirTrain track, a parking garage, and an awkwardly asymmetrical control tower—all were visible in the near distance, but the contrast of their dull brownish concrete helped make Saarinen’s freshly painted white terminal appear to gleam.

Yet I remain wary of the nostalgia the project conjures; I’m not entirely comfortable with our bottomless fascination with midcentury Modernism. And I find it disconcerting that Morse has transformed the logo and trade dress of a dead airline into a 21st-century style brand, applying it to everything, including the employees, who are costumed in updated flight uniforms.

David Mitchell courtesy TWA Hotel

The 1962 Room, an events space that was previously a baggage claim area

The flight center connects directly to Terminal 5, via an elevator (the buttons are labeled “1960s TWA HOTEL” and “PRESENT DAY JETBLUE”). When you step into the present day, the effect is jarring. Saarinen’s TWA has long been a totemic object for the design crowd, but part of its appeal might be that the vision it embodied was devastatingly wrong. It was built for a past that only barely existed and for a future that didn’t want it. Lubrano had it exactly right. The flight-center-turned-hotel is a bittersweet fantasy, a congenial spot for happily ever after: Saarinen’s very own Camelot.