“The minute the hospital said it was protocol-driven, that led me to think of isolated pods, so that they could cohort specific patient profiles within those pods,” says John Castorina, vice president and partner at RTKL.

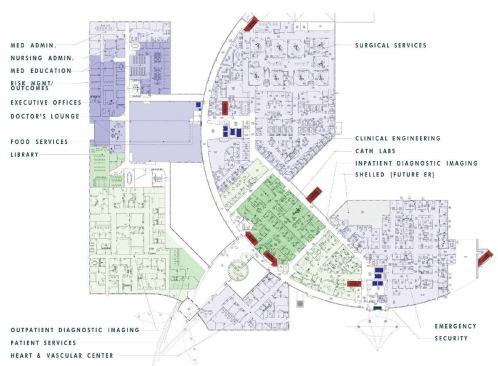

Castorina and his team designed a main corridor, or “spine,” to which three separate pods attach. Each pod houses eight private beds and all the supplies that physicians and nurses need to treat patients there. Each one has the capacity to function independently—shutting itself off from the rest of the E.D. in case of infectious-disease emergencies or dangerous psych patients—or to work in tandem with another pod.

Meanwhile, the main nursing and staff stations along the spine serve as the air traffic control, monitoring each of the pods and communicating patient needs as they develop. “Everything plugs into the spine,” Castorina says. “[The pods] can work independently of each other but still see each other.”

RTKL developed this concept after intensive consultations with medical staff. “Emergency-room physicians have to react instantaneously, and their whole job is to stabilize and transport,” Castorina says. “The most that we as architects can do is listen to what they have to say, interpret it for them, and show it to them.”

Same-handed rooms

Understanding the needs of medical staff is crucial for health care architects. For HDR, based in Omaha, Neb., that means hiring employees with medical training, such as Cyndi McCullough, a vice president who was a practicing nurse before joining the firm 12 years ago.

When Metropolitan Health Hospital asked HDR to build a new facility in Wyoming, Mich., the client wanted to employ the latest in evidence-based design. “We used information from the Institute of Medicine on patient safety,” McCullough says. “One of the things that came out of that was the same-handedness of the inpatient areas.” Traditionally, hospital rooms mirror one another, as they do in a hotel. Same-handedness makes the layout of every room identical so that doctors and nurses can move through the space more intuitively, which makes errors less likely.

Nearly all of the E.D. rooms in the new Metro Health Village hospital will be same-handed, according to project architect Jim Ulrich of HDR. It’s an expensive design proposition, since it requires individual plumbing for each unit. “There is significant research that shows same-handedness cuts down on mistakes,” Ulrich says, “so that was a very large criterion from the client.”

Going green

Another major goal was to become one of the few LEED-certified hospitals in the country. Metro Health Village—which is scheduled for completion in late 2007, at a cost of $120.7 million—will be the first hospital in Wyoming built around an entirely green master plan and will feature a green roof and water-efficient landscaping. The E.D. will be outfitted with a sustainable line of furnishings and recyclable carpeting. Even the products used to clean the hospital will be green.

Marrying evidence-based research with the latest in green technologies is no small task in an emergency department. Sometimes, the two can be at odds: Samehanded rooms, for example, require more infrastructure and plumbing than traditional patient rooms. Meeting green-certification standards and hospital regulations can be a headache for architects. HDR used both LEED and the Green Guide for Health Care (a voluntary, self-certifying metric tool kit) as a guide.

“It’s extremely hard to comply with all of the criteria for green building and still comply with health care regulations,” Ulrich says. “But it’s a stand-alone, brandnew hospital, so that made it worthwhile to try.” And the client was willing to foot the expense. “The owner was very intent on going green,” Ulrich adds.

With clients and patients demanding more, the boom in health care promises to be a rich, and challenging, marketplace for architects. “Many people say that the only way for a great architect to have a great project is to have a great client,” says Levin. “These days, it’s a very educated group out there.”

Elizabeth A. Evitts, former editor in chief of Baltimore’s Urbanite magazine, writes about architecture, planning, and the built environment.