Bruce Damonte

The Museo Soumaya in Mexico City, designed by FREE

In March, in every supermarket in Mexico City, architect Fernando Romero stared back at queuing shoppers from the cover of Quién magazine. To his right stood the gleaming paraboloid of his latest project, the Museo Soumaya in Mexico City, and over it a headline that read, “Slim’s Soumaya: How Fernando Romero Realized His Father-in-Law’s Dream.”

That’s Slim as in Carlos Slim, the man who last year edged out Bill Gates for the title of world’s wealthiest individual. The Museo Soumaya, named for the telecom billionaire’s late wife, stands as an enigmatic monument, like nothing else on the Mexico City streetscape. But though it may be Slim’s “dream,” the design is very much Fernando Romero’s. An alumnus of Jean Nouvel’s office as well as Rem Koolhaas’, the architect founded his own firm 12 years ago at the age of 28, and to date, Fernando Romero Enterprise (FREE) has realized some 25 projects. Romero’s kin and client is also the country’s biggest art collector, and for the last 17 years the works have been on display at a makeshift museum in the southern part of the city. Four years ago, Slim’s conglomerate Grupo Carso acquired a 12-acre parcel near the corner of Presa Falcon and Miguel de Cervantes, at the time a dusty industrial yard home to a tire factory. Today, christened Plaza Carso, it’s a district of modern office towers and public plazas—all of it planned, and most of the new buildings designed by Romero as a setting for Soumaya.

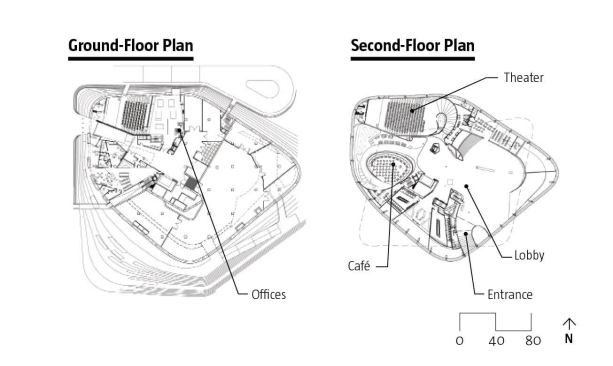

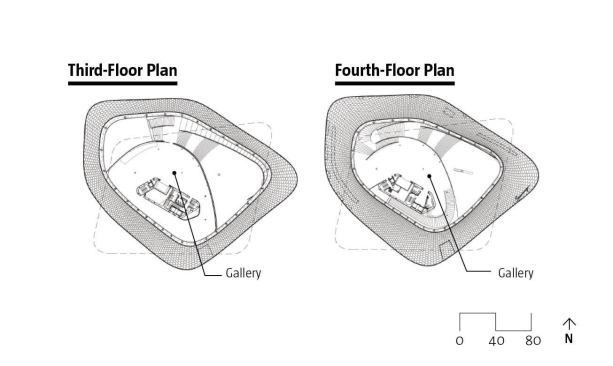

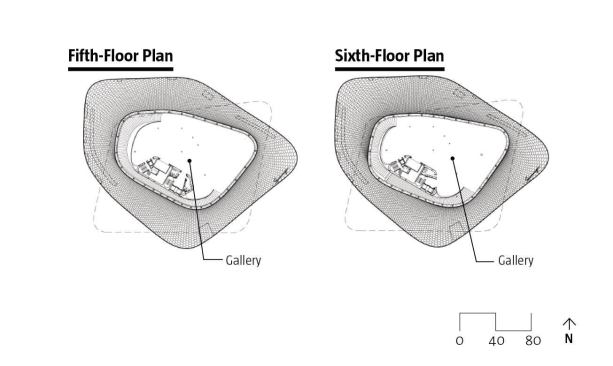

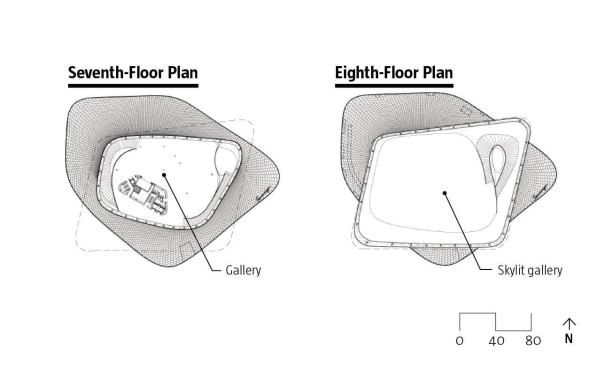

The architect was familiar, of course, with the collection that the museum was meant to house—including the largest number of works by sculptor Auguste Rodin outside France—but that was about all he and his team had to go on. When the office received the commission, “we weren’t given a museological program,” says Laura Domínguez, who’s overseeing the completion of the building interiors in collaboration with designer Andrés Mier y Teran. “All we knew was that it was to be six gallery floors and 16,000 square meters [172,223 square feet],” as well as the site where the museum had to fit in the master plan that the firm was devising for Plaza Carso. Even up to the very week before the doors were opened to the public, museum organizers were still piecing together their curatorial mission, what would go where and why.

As a consequence, no doubt, of this open-ended brief, the development of the building proceeded from the outside in. Experimenting with different formal conceits—staggered cubes and skewed and piled wedges were among the considered and discarded schemes—the designers settled on a configuration already familiar to most in the office. In 2005, FREE submitted a proposal for a landmark and observation tower for the Beijing Olympics: a looming toadstool of a building, the structure of which was to double as a dynamic screen for digital images that would roll and scroll across its surface. That project was a no-go, but its hyperbolic paraboloid outline became, with a little belt-tightening, the basic envelope for Soumaya.

It’s a form that certainly stands out in what remains a very rough-and-ready part of town. One freight train, bound for a bread factory around the corner, still rumbles past at odd hours just steps from the front door; the adjacent plot is occupied by a Costco. As an urban artifact, the museum is a bit of a sphinx, its rhetoric willfully obtuse; but the designer readily admits that conventional symbolism wasn’t on his agenda. “When you do a conceptual project [like Beijing], you’re exercising a certain muscle—you make a discovery, and then it recurs,” says Romero.

There is, however, one definitive outside referent for Soumaya—Frank Lloyd Wright’s Guggenheim Museum in New York. Romero deploys an almost identical sequence of interior ramps, though here they’re intended solely for circulation, not for exhibition: The open floors, interrupted only by a single slanted support column, are used as flexible showrooms for paintings and sculpture. This seems in part a corrective to Wright’s approach, since the suitability of his ramps for viewing art has always been in question; yet Soumaya also lacks the Guggenheim’s unity and abundant natural light, divided as it is into airless compartments. In any case, in choosing a model, Romero could hardly have shot higher than one of the world’s most famous museums.

But there is another visual cue that might also be read as a key to the design. It’s the first thing that visitors encounter on arrival: Rodin’s The Thinker, sitting alone in the wide atrium on Soumaya’s first floor. The sculpture’s torqued, robust profile, poised between thought and action, seems to make it a fairly obvious synecdoche for the brawny building in which it stands.

Toolbox: Skin

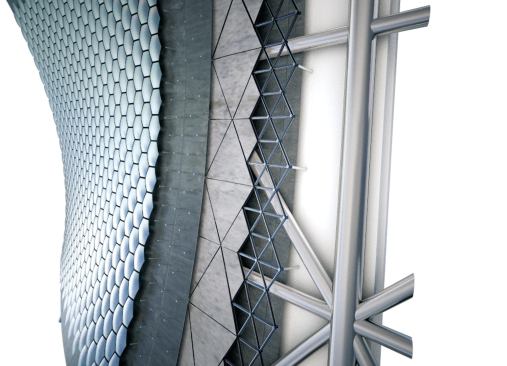

Flowers tied with yarn: that’s what Soumaya looks like under its skin. Around the building perimeter, 28 steel columns—built in segments that vary in width and position—rise from a concrete podium. These tall, tubular stalks are cinched and bound by a system of seven horizontal beams, one at each floor level, that bind the bundle together, helping bear up the floors and keeping the vertical columns from buckling outward. (The skeleton is open at the top save for an elaborate truss supporting a bubble skylight that brings daylight into the eighth-floor gallery.)

Over and around this structure wraps a nine-layer façade. With no apertures of any kind—except in the concrete base that houses the museum offices—the skin comprises, from outside in, a coat of hexagonal aluminum tiles, waterproofing layer, a series of galvanized steel plates, and a 3D mesh structure of hexagonal links. These materials clad the tubular steel structure on the exterior, but the layers continue on the other side of the supports to form the interior walls: another layer of 3D mesh, followed by a layer of gypsum panels, polystyrene insulation, concrete plaster, and finally a layer of Weatherlastic (an elastomeric wall coating) that forms the gallery walls, and from which, notably, art cannot be hung.

But the hallmark of the project is those hexagonal aluminum tiles that give the building its deflated-soccer-ball appearance. To hear the designers tell it, “nobody really knew” when the project began just how those more than 14,000 shiny scales would have to be shaped in order to adhere to the contours of such a highly irregular surface. After much prototyping, the firm finally arrived at a system of 49 discrete “families” of hexagons, with seven primary genera dominating the field. The result is not a perfectly contiguous shell, but a complex patina, the patterns of the reflective tiles alternating with the dark gaps of exposed weatherproofing snaking between them.

Worth noting, too, is the building’s focus on domestically sourced materials. Carlos Slim specified the use of homegrown building supplies whenever possible: Mexican plaster coats the museum walls, and Mexican aluminum covers the exterior. The rolled steel piping used in those vertical stems is Mexican as well—manufactured, as it happens, by a wholly owned subsidiary of Grupo Carso.

Project Credits

Project Museo Soumaya, Mexico City

Client Fundación Carlos Slim

Architect FREE Fernando Romero Enterprise, Mexico City—Fernando Romero, Mauricio Ceballos (lead designers); Ana Gabriela Alcocer, Alan Aurioles, Iván Javier Avilés, Albert Beele, Eduardo Benítez, Max Betancourt, Libia Castilla, Ophelie Chassin, Víctor Chávez, Joaquín Collado, Francisco Javier de la Vega, Manuel Díaz, Laura Domínguez, Alberto Duran, Thorsten Englert, Daniel Alejandro Farías, Omar Gerala Félix, Hugo Fernández, Matthew Fineout, Luis Flores, Raúl Flores, Luis Fuentes, Luis Ricardo García, Raúl García, Gerardo Galicia, Olga Gómez, Herminio González, Wendy Guillen, Elena Haller, Ana Paula Herrera, David Hernández, Jorge Hernández, Raúl Antonio Hernández, Susana Hernández, Wonne Ickxs, Diego Eumir Jasso, Cecilia Jiménez, Saúl Miguel Kelly, Pedro Lechuga, Juan Andres López, Juan Pedro López, Ana Medina, Cynthia Meléndez, Guillermo Mena, Ignacio Méndez, Camilo Mendoza, Jesús Monroy, Mario Mora, Ángel Ortiz, Iván Ortiz, Kosuke Osawa, Cesar Pérez, Tiago Pinto, Sergio Rebelo, Dolores Robles-Martínez, Alma Delfina Rosas, Rodolfo Rueda, Mariana Tafoya, Abril Tobar, Sappho Van Laer, Hugo Vela, Homero Yánez, Dafne Zvi Zaldívar (project team)

Interior Designer FREE, MYT—Andrés Mier y Teran (CEO)

Structural Engineer Colinas de Buen

Construction Manager Inpros

General Contractor Carso Infraestructura y Contrucción

Lighting Designer Lighteam—Gustavo Avilés

Façade Consultant Gehry Technologies

Size 336,946 square feet (including basement)

Cost Withheld

Materials and Sources

Acoustical System Consultant Omar Saad

Carpet Brio Design

Concrete Lacosa

Exterior Wall Systems Industrial Afiliara (aluminum hexagon cladding) industrialafiliada.com; Grace Construction Products (waterproof membrane) graceconstruction.com; Geometrica Design (galvanized steel plates, 3D structural mesh) gemetrica.com; Swecomex (tubular columns) swecomex.com; USG Corp. (Sheetrock) usg.com; Ypasa (poliesthirene insulation, concrete plaster, elasticated plaster) ypasa.com.mx

Flooring Hankö (German white oak) hankogroup.com; Alta Spain (Greek marble)

Furniture Industrias Ideal (auditorium seats) industriasideal.com; ArqT (carpentry)

Glass Aluvisa aluvisa.com

HVAC Dypro-Cyvsa www.cyvsa.com

Insulation Ypasa ypasa.com.mx

Lighting Lighteam lighteam.eu

Masonry and Stone PC Constructores

Metal Iasa

Millwork Hankö hankogroup.com; ArqT

Plumbing and Water System Hubard y Bourlon

Roofing Swecomex (steel structure) swecomex.com; Lacosa (concrete); Ypasa (coating) ypasa.com.mx

Wallcoverings Plaster (tecnomuro); Weatherlastic (elasticated plaster)

Wayfinding Recisa recisa.com

Windows, Curtainwalls, and Doors AGR agrpuertasmetalicas.com; Dimeyco cestek-dimeyco.com.mx