For years, the old coffee shop on Ventura Boulevard in Los Angeles lived on mostly in photographs: a swooping roofline frozen in mid-flight, boomerang geometry slicing through space, neon once blazing like a promise of a jet-age tomorrow. By the time the doors finally closed in 2020, after decades as Corky’s, the building had become something else entirely—a patchwork of alterations, a shadow of its original self, and eventually a vandalized relic slipping toward oblivion.

Today, improbably, that future-facing past has returned.

Last week, a 1958 Googie landmark in Sherman Oaks reopened as Los Angeles’ newest Chick-fil-A—not as a casual pastiche or a nostalgic set piece, but as a near-forensic reconstruction of a lost modernist interior and exterior. The result is a rare thing in Los Angeles preservation: a building that looks, feels, and spatially behaves like it did in the optimistic aftermath of World War II, even as it serves chicken sandwiches to a 21st-century crowd.

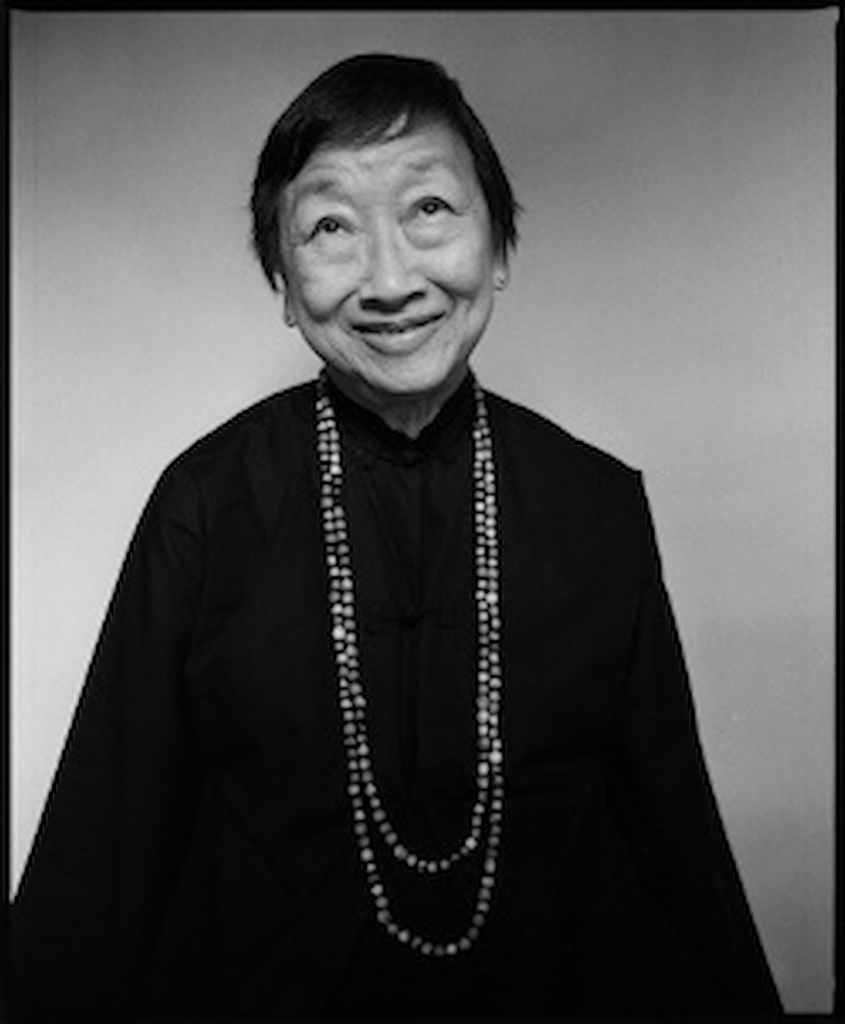

Declared a City of Los Angeles Historic-Cultural Monument (#1215) in 2020, the restaurant was originally designed by Armet & Davis, the masters of Googie architecture whose exuberant coffee shops once defined Southern California’s roadside modernism. But while the firm’s name is familiar to preservationists, the spirit animating this restoration belongs to someone whose contributions were long under-acknowledged: Helen Liu Fong.

Reclaiming Helen Fong’s Vision

At Armet & Davis, Fong oversaw interior design at a moment when architecture was still overwhelmingly white and male. A UC Berkeley–educated Chinese American designer born in Los Angeles’ Chinatown, she shaped some of the most iconic midcentury dining rooms in the region—Norms, Bob’s Big Boy, Denny’s—through a precise blend of theatrical geometry and human-scaled warmth. Her interiors were not merely decorative; they were social machines, built for lingering, conversation, and spectacle.

Over time, much of that vision was stripped away at the Sherman Oaks site. Renovations in the 1980s erased signature elements, leaving behind what one preservationist described as a “hodgepodge” rather than a coherent design. By the time Corky’s shuttered, little remained that hinted at Fong’s original intent.

That absence became the project’s starting point.

“This is our opportunity to bring her essence back,” said Miranda Lee, the designer who oversaw the reconstruction. “She was a pioneering Chinese American designer. And as a Chinese American designer myself, it’s been an incredibly full-circle moment for me to restore her work.”

Lee’s team worked closely with Alan Hess, the architectural historian who had nominated the building for landmark status years earlier. Together, they treated the project less like a renovation and more like an archaeological dig. Every surviving fragment—counter stools, terrazzo flooring, lighting fixtures, even a bold red-and-blue mosaic tile wall—was identified, cataloged, and either salvaged or replicated from original drawings.

Handwritten notes on the archival blueprints proved crucial. Some read simply, “Make sure Helen signs off on this.” For Lee, they confirmed what the spaces themselves suggested: Fong was not a peripheral figure, but a central author of the building’s identity.

A Building Rebuilt from Memory

Walking inside today feels like stepping into a Technicolor time warp. Zigzag booths line the dining room, upholstered in vivid red leather. Herman Miller Eiffel chairs anchor the seating with sculptural lightness, while George Nelson’s Bubble lamps float overhead like captured constellations. The palette is unapologetically bold; the geometry, restless and kinetic.

Outside, the restoration becomes even more radical. Dogleg-shaped I-beams—pure Googie bravado—were rebuilt and reinforced. The Palos Verdes stone walls at the entrance were painstakingly numbered, removed, and reassembled, stone by stone. Even the sign demanded fidelity: rather than LED lighting, the team insisted on real, hand-bent neon mounted on the original steel frame.

An entirely new structural system was installed beneath it all, allowing the building to meet modern codes without compromising its 1950s silhouette. “Not everybody wanted to restore this funky old building,” Hess said in an interview in Los Angeles Magazine. “They could have scraped it. But in honor of the original builder, they wanted to keep it.”

That builder, Homer J. Fuller, constructed the restaurant in 1958 as Stanley Burke’s coffee shop. The property has remained in his family ever since—a continuity that quietly underwrote the possibility of preservation when Corky’s lost its lease.

Why This Googie Survived

The project’s smooth reception stands in sharp contrast to recent preservation battles elsewhere in Los Angeles, where proposed conversions of historic coffee shops triggered public outcry. Here, circumstances mattered. The building had sat empty for years, increasingly vandalized and deteriorating. No operating business was displaced. Even longtime preservation advocates acknowledged that adaptive reuse—especially one backed by a deep-pocketed operator—was preferable to blight.

Chick-fil-A’s design team framed the effort not as branding, but stewardship. “We see it as an honor,” Lee said. “This building has meant a lot to a lot of different people. We want to preserve those stories—and a lot of those stories live in the stonework and the walls.”

There were compromises. The restaurant has no drive-thru, an unusual omission for the chain. Service will lean more toward table delivery, with servers refilling drinks and encouraging guests to linger—an echo of the coffee-shop culture Fong designed for.

A Community Room, Again

For owner-operator Brad Boerneke, who has lived nearby for a decade, the project was never just about opening another location. After a two-year franchisee interview process, he received 1,500 job applications—evidence, he says, of how deeply the neighborhood cared about the building’s fate.

“This is our community,” Boerneke said. “So many people poured their hearts and souls into this project. I want people to stay a while—meet friends in the booths—and feel welcome.”

Fresh flowers sit on the tables. The booths invite occupation, not turnover. The hope is that the building will once again function as a civic interior—a place where architecture does more than house transactions.

A company representative on site emphasized that Chick-fil-A no longer donates to political organizations and welcomes everyone. “I look forward to serving anyone who comes in here,” Boerneke added. “I want everyone to feel welcome.”

Googie’s Second Life

Googie architecture was never subtle. Born of postwar optimism and car culture, it embraced spectacle, motion, and the belief that the future could be engineered—and enjoyed—right now. That ethos aligns, perhaps unexpectedly, with a corporation willing to forgo efficiency in favor of authenticity: real neon instead of LEDs, restoration instead of replacement, patience instead of speed.

For Helen Liu Fong, whose work once defined the interiors of Southern California’s most beloved coffee shops, the reopening offers something rare: a chance to experience her ideas not as archival material, but as lived space. Her architecture is no longer flattened into black-and-white photographs or footnotes in design history. It hums again—with light, color, conversation, and the clatter of plates.

In a city where modernist landmarks too often vanish overnight, this rebuilt Googie gem offers a counter-narrative. Preservation, it suggests, does not have to mean fossilization. Sometimes, it means letting a building do what it was always meant to do—serve the public, boldly, optimistically, and in full color.