“This is not just a Postmodern revival,” Boston-based architect Sheila Kennedy, FAIA, pointed out at the final reviews at the California College of the Arts (CCA) last week. “This is the reuse of a very particular movement that employed the techniques of surrealism as a form of social and political critique.” Though that might be giving the students (and their instructors) a bit more credit for self-awareness than they deserve, it is certainly true that the return of imagery and historical reference in architecture has eschewed—luckily, as far as I’m concerned—some of the more dogmatic, self-confident, and systematic excesses that architects displayed during the 1970s and 1980s. Instead of full-blown neoclassicism or neorationalism, claims to be in tune with popular taste (except in the case of Sam Jacobs), or attempts to revive what is actually an oftentimes invented vernacular, students today are drawn to the weird and, at best, haunting juxtapositions of form and image that made some aspects of Postmodernism such a trenchant critique of the then-dominant forms of Modernism.

Courtesy Sofia Anastasi

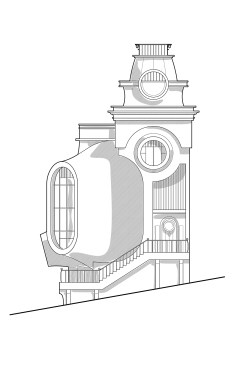

Sofia Anastasi's jury-prize-winning project for "Odd Facades"

Courtesy Sofia Anastasi

Sofia Anastasi's jury-prize-winning project for "Odd Facades"

I was confronted with the power of this unsettling approach as soon as I sat down to review CCA assistant professor Clark Thenhaus’ studio “Odd Facades.” After analyzing and researching the elements that make San Francisco’s “Painted Ladies” into such seemingly varied and exuberant celebrations of otherwise standard row houses, the students were asked to create their own row, on a fictitious street named Shady Ladies Lane. The students were each given a house to design, but then were asked to concentrate on making not integrated structures or just skins, but “odd” and fully shaped facades.

Courtesy Rajah Bose

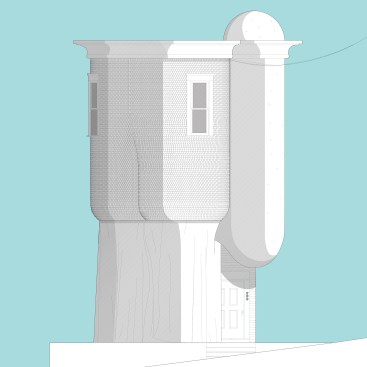

Rajah Bose's project for "Odd Facades," which was the jury prize runner up

Courtesy Rajah Bose

Rajah Bose's project for "Odd Facades," which was the jury prize runner up

The first project I saw, by Jury Prize runner up Rajah Bose, was by far the eeriest. A roughly plastered, ovoid shape protruded from the corner of what appeared to be a more or less normal San Francisco house, although the blob also sprouted smaller versions of itself up in the turret. These objects’ eyes were lined with green-dyed fake fur, and we were invited to feel the interior’s softness by sticking our hands through one of the openings. What this model meant to represent was something Bose kept ambiguous, although in one section the building did contain a grand staircase that spilled down to a swimming pool.

Courtesy Brian McKinney

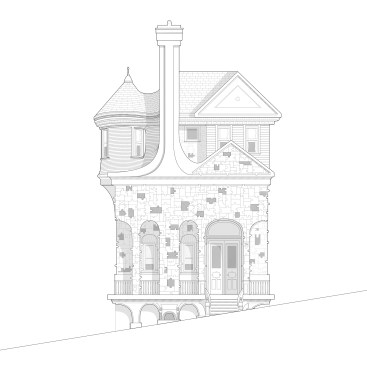

Brian McKinney's project for "Odd Facades"

Courtesy Brian McKinney

Brian McKinney's project for "Odd Facades"

Other designs on Shady Ladies Lane included houses with false fronts and blank opening, shingle roofs dripping down to the ground, upside-down turrets, and side porches that appeared only when you held a lenticular screen in the right manner. The effect was, indeed, odd. It made you realize how sunny and normal the Painted Ladies, for all their colors (which, as one student pointed out, is actually a legacy of the 1970s), really are. The students’ designs, on the other hand, brought to mind horror movies and haunted houses, sexual perversion built into form, and violence hanging from finials.

Courtesy Nic Tanji

Nic Tanji's project for "Odd Facades"

Courtesy Nic Tanji

Nic Tanji's project for "Odd Facades"

Thenhaus’ studio pointed out that you can accept much of existing building practice and find ways to transform aspects of the structure in a way that you can build identity and critique of convention into the building. The designs’ oddness was a call for otherness, difference, and the celebration of the possibilities of architecture within—but at the edges of—convention.

Courtesy Sarah Herlugson

Sarah Herlugson's project for "Odd Facades"

Courtesy Sarah Herlugson

Sarah Herlugson's project for "Odd Facades"

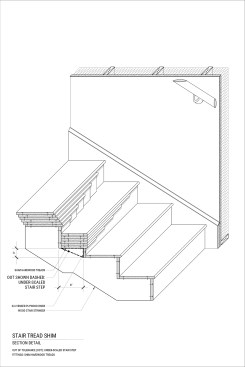

These perversions continued in the thesis projects I saw the next day. They ranged from experiments with textile and sowing that led Madeline Cunningham to create “Haptic Space and Other Guilty Pleasures” (a wall of sagging lumps that brought to mind nothing so much as Jabba the Hutt) to Taylor Metcalf’s “Out of Tolerance” (a proposal to build subtle and not-so-subtle “mistakes” into standard suburban ranch homes) which I feel was the most successful of all the projects. Although the approach was similar to research being done by other architects, Metcalf’s precision and the subtlety of his representations were disturbing. He used images from show homes and other selling tools used by developers, then Photoshopped warps into the walls and floors, or cracks into the ceilings. He also drew careful wall details and models, even devising a clamp or insert for each condition that would let contractors build the mistakes. You were left with the sense that the horrible quality of construction that is endemic to the suburban home building industry could be something we could exploit to make us wonder about our ability to cocoon ourselves from the weather, others, and even our own tripping bodies, so that we might even open ourselves up to other possibilities.

Courtesy Shailee Shah

Shailee Shah's project for "Odd Facades"

Another favorite of mine was Talitha D’Couto’s “Inside Out,” a proposal for a residential development in which each of the units was covered with materials that D’Couto took from the Bay Area Rapid Transit’s (BART) specifications. Concrete and tile became floor and ceiling covering, while also turning into patterns on bedspreads and tablecloths.

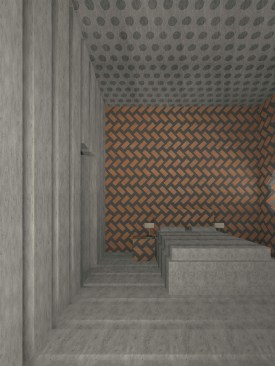

Courtesy Talitha D'Couto

Talitha D'Couto's "Inside Out"

Courtesy Talitha D'Couto

Talitha D'Couto's "Inside Out"

If the purpose of doing designs in a school of architecture is—as I believe to be the case—to explore and experiment with the building blocks with which you will later practice, then the work I saw at CCA was exemplary. The whole school breathes creativity and risk-taking. Even if not all the results are up to par, the discussion they all engendered was of the highest order. Rather than seeing such experimentation removed from schools in favor of a concentration on sellable skills, I wish it would move further out into the profession.

Courtesy Taylor Metcalf

From Taylor Metcalf's "Out of Tolerance" thesis project for CCA

Courtesy Taylor Metcalf

From Taylor Metcalf's "Out of Tolerance" thesis project for CCA

As I sat in the reviews, my eyes kept wandering out to the horrible banality of the surrounding Mission Bay, whose badly built monstrosities of apartments, offices, and university buildings now mar an area that for so many decades held the promise of being San Francisco’s future. And I was continually reminded that I would much rather see these delightfully disturbing student projects out there than all of that.