In sustainable design practices, a distinction has long been made between two methods with similar-sounding titles—Life Cycle Assessment (LCA) and Life Cycle Cost Analysis (LCCA). LCA evaluates the environmental footprint of a material or system, calculating impacts like greenhouse gas emissions and toxicity throughout its life cycle. In contrast, LCCA examines financial implications over time, from a project’s first costs to operating, maintenance, and disposal or recycling expenses.

Practically speaking, these assessments have always been conducted separately, and sustainable design curricula typically caution students not to mix the two methods. However, the two processes result in mismatched outcomes. A building product might perform well economically but have a significant ecological impact—or vice versa. Yet, as increasing environmental degradation leads to greater financial risk, separating the two considerations is impractical.

The Hidden Costs of Nature’s Decline

Many ecological impacts represent deferred, or externalized, economic ones. An example is Replacement Cost (RC), or the cost of human-made alternatives to disappearing or degraded natural ecosystem services. Consider pollination: the collapse of bee and other pollinator colonies would necessitate manual pollination—at exorbitant economic cost. A 2015 MIT study projected the cost to hand-dust the apple trees in U.S. orchards at over $870 million per year.

Why Business Can’t Ignore Biodiversity Loss

“The relationship between business success and ecosystem health has never been more critical—or more quantifiable,” writes Nicole Miller, CEO of Biomimicry 3.8, in GreenMoney journal.

The World Economic Forum estimates that more than half the world’s gross domestic product—approximately $44 trillion—relies upon nature. As corporations attempt to adapt to increasing climate volatility and ecosystem disruptions, connecting LCA and LCCA is not only practical but necessary. As Miller argues, “Nature isn’t just an environmental side note; it’s fundamental to long-term business viability and economic prosperity.”

Merging Metrics: The Rise of Integrated Assessment Tools

For this reason, one of the most active frontiers in environmental assessment is the integration of LCA and LCCA into a single methodology that measures direct and externalized impacts. Several frameworks and emerging tools aspire to achieve this goal.

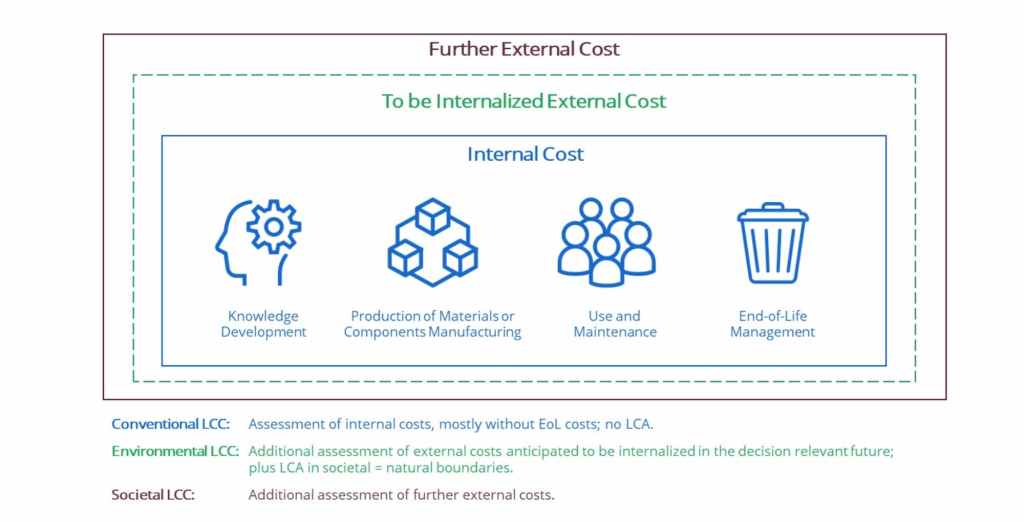

The forerunner is Life Cycle Sustainability Assessment (LCSA). Developed collaboratively by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) and the International Organization for Standardization (ISO), LCSA integrates three pillars of sustainability: LCA (environmental impacts), LCCA (economic impacts), and Social LCA (SLCA, or social impacts). LCSA aims to internalize and interrelate products’ environmental, financial, and social dimensions—the so-called “triple bottom line.” The method provides a structured framework to organize complex and varied datasets.

Eco-LCC and the Role of Shadow Pricing

Another tool is Environmental LCC (eLCC)—also known as “eco-LCC”—a model that incorporates environmental externalities into financial projections. The method employs “shadow pricing” and “damage cost models,” such as the medical costs directly resulting from air pollution, to correlate environmental impacts with economic ones. Unlike LCSA, however, eLCC is not a standalone methodology but a counterpart to traditional LCA. (A similar complementary approach, called sLCC, aims to connect social externalities and economic impacts.)

Translating Ecology into Economics: Monetized LCA in CBA

Monetized LCA in Cost-Benefit Analysis (CBA) translates LCA results into monetary impacts, such as cost-of-prevention methods and damage costs. Gaining popularity in public policy and planning circles, Monetized LCA in CBA employs established economic frameworks, such as the European Union’s ExternE model or the U.S. EPA’s Social Cost of Carbon, to translate LCA impacts like eutrophication or acidification into dollar values. The method aims to generate a single financial balance sheet with the following equation:

economic costs + ecological damage costs – avoided impacts.

Hybrid MCDA: When Numbers Don’t Tell the Whole Story

Hybrid Multi-Criteria Decision Analysis (MCDA) models consider multiple, parallel methods to solve complex problems. MCMDA approaches include Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) and Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS), techniques enabling stakeholders to evaluate environmental and economic impacts side by side. This adjacent analysis strategy is useful in circumstances where monetization is uncertain or controversial, such as cultural degradation or biodiversity loss, and allows the selective translation of impacts into currency.

Software Solutions for Design: Building-Specific Applications

Building-specific applications include software that combines LCA and LCCA, such as One Click LCA, a tool that streamlines life cycle cost and carbon analyses. This program generates comparisons of economic and environmental impacts in various scenarios. Another example is NIST’s BEES tool, which allows users to determine a percentage weighting to environmental and economic impacts. A burgeoning area of scholarship advocates net-positive approaches in which avoided externalities translate into financial benefits.

A Necessary Shift: Auditing the Triple Bottom Line

The marriage of LCA and LCCA into a unified framework is not merely a process adjustment but a conceptual shift that recognizes the inseparable relationship between the environment and the economy. Methods like LCSA and eLCC—while still developing as emerging tools—enable the AEC industry to assign financial impacts to ecological degradation, providing a more holistic view of the consequences of design and construction decisions.

The Economic Price of Ignoring Nature

These ramifications are palpable, and occurring in realtime. According to a BloombergNEF study of 10 major corporations, misguided environmental decisions resulted in $83 billion in direct losses. Furthermore, the World Economic Forum estimates that worldwide GDP will decline by $2.7 trillion each year by 2030 due to global biodiversity loss.

It will therefore be critical not just to avoid environmental impacts but to invest in ecosystem services—the ultimate net-positive approach to the comprehensive ledger. “Without strategic Nature investments, businesses face existential threats,” explains Miller. “Ecosystem collapse is not just an environmental problem—it’s the unraveling of the systems that sustain civilization itself.”