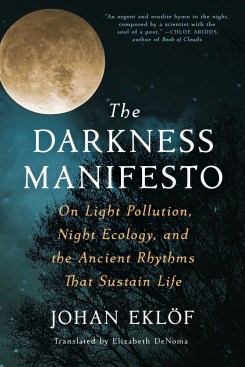

The evidence of the Anthropocene is typically described as material changes (think: modifications to the planet’s surface, the accumulation of waste plastic in the world’s oceans, or excess carbon in the atmosphere). But humanity’s outsize impact on the Earth is also represented by the influence of light. According to scientist Johan Eklöf, “Every city and every street is visible a long way out in the cosmic darkness, which is perhaps one of the most obvious signs that we have entered a new era: the Anthropocene, the time of humans.” In The Darkness Manifesto: On Light Pollution, Night Ecology, and the Ancient Rhythms that Sustain Life (Simon & Schuster, 2023), Eklöf describes how our addiction to nighttime illumination is problematic for many planetary species, and ultimately entire ecosystems, requiring a holistic reconsideration of outdoor lighting.

Half of insect species are nocturnal, as are a third of vertebrates and nearly two-thirds of invertebrates—thus, “most of nature’s activity” takes place during the night, explains Eklöf. Light pollution, or excess illumination, creates detrimental effects among many species. Moths, for example, are disoriented by light pollution, which either confuses them as sunlight or attracts and blinds them, making them easy prey. Moths play a significant role as pollinators, and are as effective as bees in this imperative ecological function. Yet light pollution is influencing moths’ declining numbers, thus reducing pollination in plants. Who would have known that the health of ecosystems would be fundamentally endangered by electric light?

The term light pollution was originally used in reference to the undesirable obfuscation of the starry sky, but since has assumed a much graver connotation. The International Dark-Sky Association offers five principles, developed with the Illuminating Engineering Society, that all outdoor lighting applications should follow to avoid light pollution. The principals are: “all light should have a clear purpose” (useful); “light should be directed only to where needed” (targeted); “light should be no brighter than necessary” (low light levels); “light should be used only when it is useful” (controlled); and “use warmer color lights where possible” (color).

Entire ecologies are at risk. Reestablishing nighttime darkness should be a fundamental goal for the modification and design of the future built environment.

Lighting suppliers like North Dakota–based Border States offer guidelines on dark-sky compliant fixtures. These are essentially full cutoff fixtures, meaning they emit light only below a horizontal plane, thus minimizing light trespass and glare. The IDA maintains a Fixture Seal of Approval program certifying fixtures according to these guidelines including the minimization of cool-temperature light (which is particularly undesirable as it is most closely associated with the mid-day sun). Examples of IDA-approved lighting include Dark Sky Luminaires from Hillsboro, Ore.–based Ligman Lighting. The company’s Arizona Light Column exemplifies its “Turtle-Friendly Amber LED” approach, providing warm-spectrum illumination within a confined radius so as not to confuse sea turtle hatchlings attempting to navigate by moonlight.

Existing outdoor light fixtures can also be modified to limit light trespass by using light shields. For example, Ferguson offers the Nightsaver Collection of shields that deliver full cutoff illumination. Parshield manufactures a clip-on visor for floodlight and spotlight PAR-38 bulbs installed outdoors. According to the company, residential lighting, the product’s primary application, is responsible for up to 45% of light pollution. Light shields can ensure that illumination is delivered to the desired areas, minimizing light trespass and glare.

In many contexts, electric lighting may be altogether unnecessary. Photoluminescent materials can be incorporated into path surfacing to enable effective wayfinding without risking light pollution—or the need for electricity. For example, Austria-based engineering firm TPA designed a glow-in-the-dark bike path in Lindzbark Warminski, Poland. The installation incorporates so-called luminophores in the asphalt surfacing, and these photoluminescent aggregates absorb energy from sunlight throughout the day. At night, the path emits a blue light for up to 10 hours. Another technology, LuminoKrom photoluminescent paint, offers an effective means to delineate roadway borders and vehicular lanes for nighttime travel. French company OliKrom worked with Eiffage Group’s construction and engineering branches to develop this paint to withstand heavy traffic and weathering, offering virtually unlimited light recharges.

courtesy Simon & Schuster

Ultimately, curtailing humanity’s increasing and excessive use of nocturnal illumination will require overcoming deeply held cultural associations. Eklöf cites nyctophobia, or fear of the dark, as the primary motivator of outdoor lighting. However, the default ways that we illuminate the built environment using light-polluting fixtures are not helpful in overcoming this phobia. Studies show that security is often thwarted, not enhanced, by bad lighting installations, as glare can make it more difficult to see into shaded areas. In addition, typical nighttime lighting hinders our eyes’ inherent, albeit slow, tendency to develop night vision. According to Eklöf, “One look at a streetlight, a cell phone powering on, or a passing car with headlights breaks down our rhodopsin—our light-sensitive visual pigment—which falls down like a house of cards, and the eye is forced to begin again.”

For architects, embracing the darkness feels deeply counterintuitive. After all, architecture is a visually centered medium that has long been defined by its relationship to light, at least in the Western tradition. As Le Corbusier summarized in his 1923 book Vers une Architecture, “Architecture is the masterly, correct and magnificent play of masses brought together in light.” An alternative perspective can be found in Junichiro Tanizaki’s 1977 text In Praise of Shadows, which celebrates the subtle nuances and details present in shadows that are otherwise obliterated by a single harsh light bulb. Surrounded as we are by the bright glare of modern illumination, Tanizaki emphasizes our need to reclaim what is becoming a vanishing experience: “It is an indescribable feeling to sit curled up in the semi-daylight sunk deeply into meditation in the feeble light.”

Nocturnal darkness is not merely a choice; it is a necessity. “Life has evolved in accordance with the day’s alternating light and darkness, and the more animals we study, the more we realize that both day and night are equally important for their ecology,” Eklöf writes. Over two-thirds of moth species—organisms that are crucial for the continuation of plant life on Earth—are now disappearing, in no small part due to light pollution. And many other life forms that rely on nocturnally active insects, such as bats, are also endangered. As a result, entire ecologies are at risk. Reestablishing nighttime darkness should therefore be a fundamental goal for the modification and design of the future built environment. After all, life on this planet—and ultimately of our own species—depends on it.

The views and conclusions from this author are not necessarily those of ARCHITECT magazine or of The American Institute of Architects.

Read more: The latest from columnist Blaine Brownell, FAIA, includes the carbon footprint of material obsolescence, new questions about society’s reliance on toxic substances, and the importance of improving air quality.