Project Description

Out along the Atlantic coast east of New York City, off the south shore

of Long Island, beyond the reach of the suburbs and the exurbs and not

quite yet at the Hamptons, you can find one of the country’s truly

special places. Fire Island is a collection of a few dozen

settlements—some still little more than camps, some almost now becoming

real towns—dotted out for 30 miles along the pine-covered dunes of the

barrier island. There is no access by car except for the few that crawl

over from time to time along the beach from Robert Moses State Park (his

plan for a highway through the island was never realized), and in most

towns the thoroughfares are no more than graying wooden boardwalks,

along which residents tote their supplies home in little wagons from the

ferry docks.

Not unlike some other East Coast islands—Martha’s Vineyard, for example,

where every one of the little villages has a unique personality—Fire

Island is a collection of very different places: shingly,

family-oriented Saltaire; the almost-hopping, almost-downtown Ocean

Beach; the exclusive Point O’ Woods; honky-tonk Ocean Bay Park. And then

there’s the Pines: The woodsy, beachy getaway that is New York’s gay

capital of summertime leisure-by-the-sea. Elegant by day, devil-may-care

by night.

Fire Island as a whole is a vulnerable place, little more than a sandbar

really, and from time to time hurricanes and winter storms will punch

through the few hundred yards between the ocean and the bay. Because she

made landfall just to the west, last year’s Superstorm Sandy did not

entirely wash away Fire Island, though it did significant damage. But

about a year before, there was another disaster—an off-season fire that

gutted the old Pavilion nightclub that was the beating heart of life in

the Pines, and one of the liveliest spots on the island.

“It could have been a lot worse,” says Matthias Hollwich, partner at New

York firm HWKN and chief designer of the new building that has risen up

from the ashes. “If the wind had been blowing the other way, they could

have lost the whole town.”

When you arrive at the little harbor at the Pines after a half-hour trip

across the Great South Bay, what you see are some houses—surprisingly

modern (many designed by the likes of Horace Gifford, Arthur Erickson,

Harry Bates, and Andrew Geller); some boats (among them on the day I

visited was a 40-foot sloop called, unforgivably, “Untidaled”); one

short five-building row of shops and hotels; and at the end of the line,

at the head of the harbor where the ferry docks, the Fire Island Pines

Pavilion.

It’s the heart of the town, with its club and bars and shops, and the

focus of after-hours revelry that starts early on summer weekend nights.

“It had to be iconic as a program,” HWKN’s other founding partner, Marc

Kushner, AIA, says. The fabled “high tea”—a weekly dance party, cousin

to the “low” and “middle” teas held elsewhere down the strip—had for

years taken place on the old Pavilion’s second-story deck, overlooking

the harbor and the town. When it burned, in November 2011, that beloved

ritual was interrupted. There was enormous pressure to bring the

building right back. And to bring it back right. And that meant a lot of

very interested parties—including the owners of each of the Pines’ 700

homes.

“It’s a very difficult assignment, in a way,” says developer Matthew

Blesso, one of the property’s owners and operators, about the marching

orders he gave his architects. “There’s no program for: How do you

design a gay nightclub at a seasonal gay beach community? It’s not like

you can look elsewhere and see how it has been done. The Pines is not

Mykonos. It’s not South Beach.”

The community took the result of the fire as an opportunity to rethink

the commercial strip, engaging Diller Scofidio + Renfro to design a

master plan. The new Pavilion, which opened in time for this summer

season, is a lynchpin, and looking at the structure that HWKN raised at

the end of the harbor, there is no doubt that it is pure Pines: elegant,

bold, and a little rough around the edges.

The takeaway from the community’s commentary, heard directly at several

public meetings, Hollwich says, was that the previous building—a typical

clapboard seaside shack—was “too neutral, too generic.” The residents

wanted the new building to be “supercharged,” he says. Music to the

ears, no doubt, of an architect at an emergent New York firm (designers

of the epically successful spiky blue folly named “Wendy,” the 2012

installment of the MoMA/P.S.1’s Young Architects Program) who spent four

years working in Rotterdam at OMA.

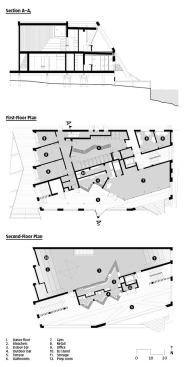

And there is something of Rem in the Pavilion, an attitude toward the

frank disposition of materials—in this case, cedar, everywhere—that,

like the spaces at OMA’s Illinois Institute of Technology (IIT) Student

Center in Chicago, still manages to border on the effete. And then

there’s the countervailing bold gesture, as in the train tube at IIT. In

the Pavilion, this takes the form of an exaggerated,

not-quite-structural trestle across the front of the simply supported,

two-story structure. The Parallam beams are dexterously exposed

throughout, as are the cedar joists (on only 15-inch centers to better

fit the controlling dimensions). And the beautiful railings

rendered—temporarily, alas, until the steel subcontractor delivers that

final touch—in OSB, God’s very own favorite sheet material, of course,

but not quite the thing for a building left out to weather by the sea.

And the building is already weathering, as planned, toward the stone

gray that will fit it even better into the ocean-beaten context of the

town. The building is well thought-out for its purpose, from the clever

steps and walkways leading from the board-paved plaza where the ferry

lands, to some of the most elegant public bathrooms imaginable

(gender-non-specific and cheekily free of mirrors), all the way up to

the operable skylight in the top-floor dance hall that makes it a very

pleasant place to be, even during the day. The building works. But it is

the delicate disposition of its almost-brutal materiality, that bold

new face for the Pines, that makes it a true success: It gives Fire

Islanders once again a proper place to dance away the night. The feel of

the building, its elegance, its boldness, and its roughness, more than

any single decision or detail, is what makes it so right.

“Historically, you have a group of men who have two lives,” Blesso

explains. “Life in the city, then life in the Pines. There’s a freedom

for people to really be themselves in a way maybe they can’t be

elsewhere. It’s a place where people can really express themselves—and

you see that architecturally as well. It’s normal there to go over the

top a little and be a little flamboyant. But at the same time it’s a

really casual place.

“We needed architecture that really embodied both of those things: It

needed to be warm, but also strong. And I think the design is very

masculine. Which is fitting.” —Philip Nobel