Project Description

You don’t expect an architect to compare a 38-story office building he co-designed to Marcel Duchamp’s 1912 Nude Descending a Staircase (No. 2),

the painting that caused such a scandal when it brought cubism to

America in the 1913 Armory Exhibition. That is especially true if the

architect is an American, the tower is in Paris, and he is a partner at

New York–based Robert A.M. Stern Architects (RAMSA),

the firm most of us associate with polite and expensive Neo-Classicism.

Yet RAMSA partner Kevin Smith, AIA, who—together with fellow partner

Meghan McDermott, AIA—designed the recently opened 489,700-square-foot

Tour Carpe Diem, insists that this is “a cubist building—and a bit of an

anthropomorphic one.”

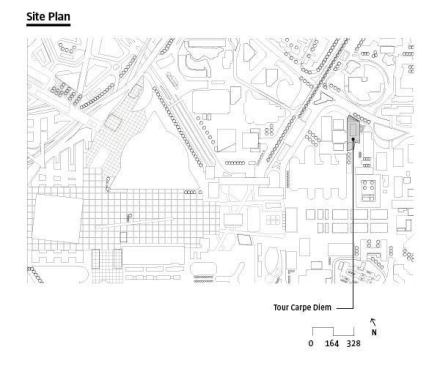

The tower, a speculative development for insurance company

Aviva

in Paris’s La Défense district, is modernist in its skin and bones, as

well as in its site and siting. The latter is the main reason for the

building’s slickness and vivaciousness: It is located in the area that

the French have built up, since the 1960s, into the largest office

complex in Europe (comprising almost 60 million square feet). Dozens of

isolated office towers stand on a large plinth (or

dalle), known as “the Pear” because of its shape, which sits

at the end of the same axis as the Arc de Triomphe and the Louvre. The

plinth, in high modernist fashion, contains all of the services that get

people in and out by car or train, not to mention mechanical and trash

services. In recent years, the

Établissement Public pour l’Aménagement de la Région de la Défense

(EPAD), the agency that runs the district, has tried to humanize this

pedestrian environment and lunchtime eating and shopping area by

renovating the few housing blocks in the area, but it remains a fortress

of big business.

Carpe Diem is, in fact, the first building to break out of the Pear’s

confines by adding a stair connecting the plinth to the adjacent

neighborhood, Courbevoie. “Everything comes from that diagonal

connecting the dalle to the neighborhood for the first time,”

Smith says. “The diagonal offsets of the north and south façades, and

the public interiors make visible that cut.”

The zigzags of the short façades are what define the Carpe Diem. Smith

and McDermott designed them both to break down the building’s mass, and

to provide the structure with an identity. They also ensure “that the

tower always looks different, depending from where you see it, and what

the light is like,” McDermott says. “We wanted it to come alive in this

otherwise rather dead setting, even in gray weather.”

The architects, who developed the design for a competition in 2008,

responded both to the specific and the general context. “As Americans

coming to Paris,” Smith says, “we picked up not just on the art that

helped change our culture, but also on the diagonals hidden in French

architecture: the struts in the Eiffel Tower and inside the Statue of

Liberty, Eugène Viollet-le-Duc’s constructions, and even the boulevards

crossing Paris.”

This responsiveness to both the specific and the general site continued

in the designers’ choice of glass. “We wanted something that was more

blue-silver than bronze or green, so that it would dissolve into the sky

from some angles, while being transparent from others,” McDermott says.

They gave the folded, short sides shadow boxes for the moldings to

emphasize the building’s mass, while making the long sides sleek and

transparent to maximize views and lighten the building’s mass.

Within this acrobatic mass, Carpe Diem’s public spaces open up its

narrow site at ground level, while expanding the views at the top. “We

really wanted to emphasize and strengthen the new connection,” Smith

says, pointing to the broad stairs that run up to the dalle

both inside and outside the building. The opening in the plinth “was a

request from Courbevoie and EPAD,” says Joelle Chauvin, the managing

director of Aviva Investors Real Estate France, and the project’s

client. “But what was wonderful was the way Stern responded, with this

grand staircase both inside and out, that really made a wonderful sense

of drama and ease out of the connection—it is superb.”

The tower has two front doors, one at the street and one on the plinth.

In addition to the employee cafeteria on the ground floor and a full

restaurant on the second floor for the 3,000 employees who will work in

the building (a number that was mandated by French law), the developer

also asked for an “oasis” within the “stone world of La Défense.” They

wanted “something more ancient and still within the mineral and modern

world of La Défense,” Smith says. Smith’s and McDermott’s response, in

collaboration with landscape architect Ronan Gallais of Mutabilis, was a

sunken winter garden, complete with a green wall, filled with both real

vines and bronze ones created by the artist Stéphanie Buttier. “The

winter garden was my idea,” Chauvin says. “It is a bit of theater. Now,

it is also a place for relaxation.” An adjacent spa facility increases

the possibilities to retreat in this cavern rescued from the tangle of

service tunnels and mechanical equipment stowed in the plinth all around

it.

The public space reappears at the tower’s top. Carpe Diem’s roof is a

garden where employees can take in the air and the views over Paris

while remaining sheltered behind the glass façade that continues up past

them. Equally lavishly planted, this space is the active and

outward-looking counterpart to the base’s junglelike garden. Here,

adjacent meeting rooms that resident firms can book are the alternative

to the base’s place of isolation and relaxation.

In-between all these generous spaces, 14,000-square-foot floors stack

up. They are relatively small, at least by American standards, but the

eccentric loading of the core to the west allows for large expanses on

the building’s more light-filled eastern side, while the western side

accommodates private offices along a fire corridor. As the facets only

occur on the two narrow sides that are visible from the surroundings,

creating dramatic corner conditions, the long faces remain more

workmanlike and efficient. The floors also have 9-foot clear ceiling

heights and no interior columns (a rarity in French office buildings),

in order to allow for the most flexible use.

For all of its fracturing of the glass office tower and addition of

places of circulation, or just hanging out, in a manner that ameliorates

the sameness inherent in the modern office tower, Carpe Diem’s most

remarkable achievement remains invisible. A combination of factors—the

glass façade’s angles and its surface performance, the building’s

orientation, computer-assisted shading and energy distribution, on-site

ice storage, recycling of rainwater collected from the roof garden,

chilled beams in the office floors, use of La Défense’s central steam

heat for standard energy loads (letting internal heating and cooling

manage peaks), low general lighting combined with high-performance task

lights, bicycle parking, and, last not but not least, geothermal

wells—means that this building achieved both LEED Platinum status and

its French equivalents, the designations of a Bâtiment de basse consommation (Building with low usage) and Très haute performance énergétique

(Very high energy performance). “If it wasn’t for some peculiarities in

the local code,” Smith says, “we could have made this a net-zero energy

building.”

In its appearance, in the way it opens up its public spaces at every

level, and in the way it works, Tour Carpe Diem is a model of a

light-footed office building. “The way Kevin and Meghan developed the

design was very chic and free,” Chauvin says, “but also new and

energetic.” Against the closed boxes that surround it, but also in

contrast to RAMSA’s more closed constructions, this is a structure that

continues the modernist dream that architecture should reflect, refract,

and open up the world around it, using the latest technology to make us

both more comfortable and more at home in a world many see as alien. In

one of the world’s most maligned bastions of modernism, this denuding

of the modernist traditions is ascending, rather than descending,

towards a vision that is, in however incremental a way, more pleasant

and hopeful than the one that came before. —Aaron Betsky

CORRECTION: In a previous version of this article, Robert A.M.

Stern Architects was misidentified as Robert A.M. Stern Associates. We

regret the error.