U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

Paul Jaskot

On Nov. 4, art historian Paul Jaskot delivered the Joseph and Rebecca Meyerhoff Annual Lecture at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. In “Architecture of the Holocaust,” he described the planning of the concentration camp of Auschwitz-Birkenau and the building activity that took place there, especially during the years of 1943 and 1944, and engaged in by thousands of women prisoners as well as men.

ARCHITECT talked with Jaskot—a professor at DePaul University who is currently the Andrew W. Mellon professor at the National Gallery of Art’s Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts—about his research, and why questions of labor and construction matter in architectural history.

ARCHITECT: My first question was about the discovery that construction was a

primary activity at Auschwitz. It seems like that hasn’t been widely known

before, so why do you think it’s been overlooked?

Jaskot: Well, I think there are two

reasons behind that. The first is that when we think about architecture, even

architecture of the SS, we think about design and the finished building. This

is just standard, even though architectural practice, we know, is much deeper.

Secondly, Holocaust studies tends to think of cultural aspects like

architecture as very much secondary to a bigger picture of genocide or of the

military, or of what we might call hard-nosed politics of the Nazi state. The

result is that as with architectural historians, they’re thinking of the end of

the building, not the building itself.

One thing you mentioned—along with the startling fact that

thousands of people were involved in construction at the camp—was that there

were more than 100 people employed as draftsmen.

At least 160 in 1942.

I wondered about those people in

particular. Did they have architectural training?

Unfortunately, we don’t know a

lot about them right now. A lot of those individuals exist merely as prisoner

numbers. Connecting them to actual people—that work hasn’t been done yet, and

is something that I am definitely following up on.

That said, of the people that we do know, some of them were indeed trained architects. And they were mostly coming out of Poland, and also what was then German Silesia. They were working with a wide variety of different inmates of very different skill levels. Some had nothing more than a technical drawing course that was the equivalent of high school. Others were industrial artists or they were even fine artists.

Some people just got lucky and they were assigned that work, because that actually was good work. It was inside; it wasn’t heavy lifting. It was still, of course, forced labor, and it wasn’t great, but your chances of survival were slightly better.

U.S. Holocaust Memorial Museum

Jaskot delivering the Joseph and Rebecca Meyerhoff Annual Lecture at the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum in Washington, D.C. The image behind him is a viewshed visualization by Chester Harvey that shows what a guard could see from the ramp of Auschwitz-Birkenau.

It’s surprising

that women were so involved in the construction. You mentioned how, in their survivor

testimonies, often these memories of construction are disjointed and break into the main narrative. What’s the difference between women’s and men’s

narratives?

We should remember that any sample of

testimony is a partial sample. But of the sample that I’m working with, what is

interesting is that the men are almost always asked by the interviewer, “So

what were you building? What was the space you were working in?” And the men

very easily talk about their labor and that becomes a bigger part of the

narrative. It’s part of their story of survival.

For the women on the whole, and I’m generalizing, they have to force it into the narrative, because it’s not their story of survival in the same way—or at least it’s not presumed to be their story, [either] by the interviewer [or] sometimes by the women themselves.

Another

thing I took away from the lecture was the chaotic, improvisational nature of

the construction. At the beginning, you showed the plan of how the SS was going to build this enormous complex, and the construction you then graphed

showed a picture of stopping and starting all the time. For you, was that a surprise?

Well, those of us who have studied the Holocaust

and architecture would not be surprised that there was simultaneously a

long-term plan that was consistently worked on as well as short-term adaptation

to the war and to the conditions of the war. What surprised me was how variable

that was at a daily level.

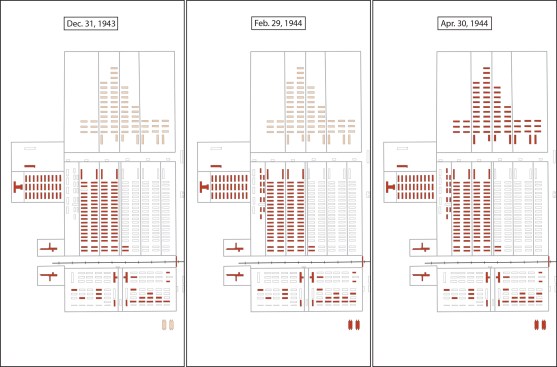

One thing that’s interesting about the digital map [that Jaskot created with geographer Anne Kelly Knowles] is, they’re building all over the site of Auschwitz-Birkenau—they’re not building from the gates backwards. It’s clearly much more random than that. And that seems to me really interesting, because these [Nazi] architects, many of them were trained in the Weimar Republic, so they all knew about new theories of urban planning and they’re looking at Bruno Taut and Ernst May, and they too are now building a city, essentially. And the organization of that city is so chaotic.

Maps by Benjamin Perry Blackshear from buildings database by Chester Harvey. Figures from Geographies of the Holocaust (Indiana University Press, 2014), edited by Anne Kelly Knowles, Tim Cole and Alberto Giordano.

Construction phases at Auschwitz-Birkenau in 1943 and 1944. Red represents completed buildings, pink represents buildings under construction, and grey represents the structures that were planned or construction status was uncertain.

What do

you read into that, in terms of the larger operation of the camp?

Well, one thing is that I think we need to be

more attentive to the labor population in construction. Who they were, how they

were being treated, the weather that day—all those factors that we rationally

know are part of any construction site here get exaggerated because of the

oppression involved in forced labor, and also the intensity of labor to support

the war effort and instruct genocide.

Why was that labor population [at Auschwitz] so variably used? I mean, they had 10,000 workers at their disposal on a daily basis if they wanted them. So why doesn’t that graph [of building activity] gradually go up? These are questions about labor that we really haven’t asked.

You mentioned that the construction industry in

Germany was deeply involved in the Holocaust camps.

Most of the major

construction firms—well, all the major construction firms—used forced labor,

but most of them also controlled their own sub-camps. We have to remember there

are over 1,100 camps and sub-camps in the SS system by 1944. Many of these

sub-camps were overseen by the SS in terms of the guards, but they were really

run by industry. One of those industries was the construction industry. They

[had] really expand[ed] their capacity to work at scale in the ‘20’s and the ‘30’s,

and become much more involved in government policy. So there’s a kind of

conjunction, if you will.

Konrad Kurzacz/Wikimedia Commons

More than 1 million people were murdered by the Nazis at the concentration camp of Auschwitz-Birkenau in Poland. Its main gate house—familiar from the movie Schindler's List—has become an indelible symbol of the horrors that took place inside. But is it not just a symbol. Like any other building, it was constructed in stages, by human hands; in this case, by the hands of the very prisoners it confined and gassed. The seam in the front wall shows construction stopping and starting, a powerful reminder of the grueling forced labor that went into building Auschwitz over a period of years.

This interview has been edited for clarity and length.