At the end of my recent conversation about the luxury condo market with David Von Spreckelsen, who founded Toll Brothers City Living (TBCL) nearly 15 years ago, he pitched me the company’s newest development, 91 Leonard, in New York City’s Tribeca neighborhood. Designed by Skidmore, Owings & Merrill, the building’s units start at $795,000 for a studio, include one-bedrooms for $1.3 million, and feature three- and four-bedroom penthouse units for $8 million to $10 million. “Much of Tribeca is filled with big, expensive lofts,” Von Spreckelsen said. “We’re bringing much more affordability to Tribeca.”

It’s the sort of statement only a luxury condo developer could make. Affordability in the $1 million-plus price range? But it’s also the sort of statement one doesn’t expect a luxury developer to make. After all, luxury connotes unaffordability and extravagance. Moderation would seem like the wrong note to strike when marketing a multimillion-dollar condo replete with high-end finishes and appliances, and the full complement of amenities—pools, weight rooms, movie screening rooms, and lavish rooftop decks.

courtesy Toll Brothers City Living

91 Leonard

But as the upper echelons of housing markets in cities across the country continue to soften, Von Spreckelsen’s pitch reflects a growing trend among luxury condo developers. They are both talking up and building more condos priced between $1 million and $3 million, a segment the industry increasingly calls “affordable luxury.” Jonathan Miller, president and CEO of the real estate appraisal firm Miller Samuel, identifies luxury condos priced at $3 million and under as “the sweet spot of new development.” According to housing data that Miller Samuel collects for real estate company Douglas Elliman, this segment accounted for 38 percent of sales in New York City’s luxury housing market over the past year.

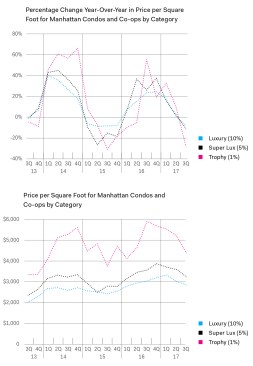

When Manhattan’s housing market peaked in 2014, sales were particularly robust for condos selling for $10 million and higher, a segment the industry calls “superluxury.” Since then, the superluxury market has flattened. Penthouses priced at $20 million, $40 million, or $60 million are more likely to sit on the market for months, maybe even a couple of years, and sell for less than their asking price. Of course, even a $60 million condo that sells for $45 million—25 percent under the asking price—is still likely to be the most expensive on the block. “Sellers are making bigger discounts and still helping the market set new records,” says Miller, who called this a defining paradox of today’s housing market.

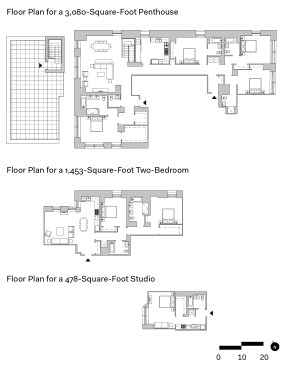

courtesy Toll Brothers City Living

Floor plans from 91 Leonard

Nonetheless, developers like Toll Brothers have begun to recalibrate. “There came a point a few years ago in Manhattan when it became almost impossible to buy [a condo] for less than $2,000 a square foot. It even started stretching to $2,500 and even $3,000 in certain instances,” Von Spreckelsen said. “What happened next is that supply caught up with demand, and we started to run out of buyers who really had the wherewithal to pay these exorbitant prices.” Like other luxury developers, TBCL has started to offer occasional incentives to move its most expensive units, like paying buyers’ estate taxes, lawyers’ fees, and other closing costs.

But the company is also looking to build more condos that it can sell for less than $2,000 a square foot, primarily by shrinking the footprints of units. Part of what a luxury condo buyer pays for is “a generosity of space,” Von Spreckelsen said, like large, five-piece bathrooms and walk-in closets. He imagines a buyer of less expensive luxury condos willing to forgo this kind of generosity. “It’s for the buyer who says, ‘Okay, maybe I don’t need a separate soaking tub in my bathroom, and I can live without a walk-in closet.’ … If we can bring stuff to the market that’s below $2 million, let’s say, when almost everything is above $2 million, we’re certainly looking for opportunities to do that.”

source: Miller Samuel/Douglas Elliman

Recent declines in the sales prices of trophy and luxury condos in Manhattan has inspired Toll Brothers and other developers to build more units that sell for less than $2,000 a square foot.

Branding for the Anxieties of Affluence

It turns out “affordable luxury” may be a particularly smart way to market expensive condos today. Rachel Sherman, a sociologist at the New School for Social Research in New York, explains in Uneasy Street: The Anxieties of Affluence (Princeton University Press, 2017), her study of wealthy New Yorkers, that many of today’s most affluent families are reluctant to display their wealth and instead value an ideal of moderate consumption. “Internal conflicts about their wealth cropped up especially in their feelings about their living space,” she writes. Some dislike using the word “penthouse” to describe their homes. Many prefer to think of themselves not as rich, Sherman writes, but as “symbolically belonging to the broad middle.”

“People want to be morally worthy, and moral worth in the U.S. is associated with middle-ness,” Sherman told me. It’s the idea that, she said, “we’re all hardworking Americans, who are being reasonable consumers and giving back to society in some way, and raising our kids not to be snobby and entitled.” She said a term like “affordable luxury” could be a successful way to brand expensive homes because it sounds “a little bit modest, relative to what you could have and relative to what people you might think of as more ostentatious would have.”

Sherman also noted the important difference between what someone buys and how they talk about it. Many families in her study framed their purchases as more moderate, as “one step down,” she said; Sherman recalled a woman who reported that she only bought clothes from “the cheap floor at Barneys”—the sales rack. For Toll Brothers, highlighting the affordability of a $1 million condo is a similar performance of moderation; that is, it’s a new brand rather than a new product. Von Spreckelsen acknowledged as much, too. “It’s a little tweaking,” he said of these smaller units. “We’re not talking about doing something radically different.” It’s the difference, say, between a large bathroom with both a tub and a shower and a smaller bathroom with only the latter.

121 East 22nd Street

Toll Brothers has made a practice of stretching its brand to accommodate its customers’ shifting tastes. About 15 years ago, Robert Toll, who has been mainly dedicated to building luxury single-family homes since he founded his company in 1967 with his brother Bruce, hired Von Spreckelsen to expand into urban centers, starting with Philadelphia and then New York City and New Jersey. “Bob saw his relatively affluent clientele selling their suburban homes and moving back to cities, so he followed his customers,” Von Spreckelsen recalled, noting that TBCL is looking to break into Boston, Miami, and Los Angeles, among other markets. Building more lower-tier luxury units is another instance of the company following its customers’ preferences and values. Ostentation is out; relative moderation is in.

Affordability, especially in the context of housing, hasn’t always been regarded as a virtue, of course. When I spoke to Miller, he recalled hearing the phrase “affordable luxury” half a dozen years ago at a conference among developers and real estate brokers. “The audience was aghast,” he said. Though he, and likely many others, correctly understood the phrase to mean “the entry level of luxury,” as he calls it, he said it also sounded offensive, “a little too condescending to the general populous.” The phrase “affordable housing” once meant government-subsidized housing, with all of its associated stigmas. These days, however, as more people living in cities struggle to find housing they can afford, the connotations of the phrase have changed. “Today it means middle-class,” Miller said.

courtesy Toll Brothers City Living

121 East 22nd Street

To the extent that condos branded as affordable luxury reflect wealthy customers’ anxieties, then, they also reflect the general public’s need for more affordable homes. Which is where such branding becomes problematic. Terms like “affordable luxury” and “superluxury” distort a sense of what’s reasonable. “These homes start to sound cheap when in fact they are still really expensive,” Sherman said. In 2016, New York City’s median income was $58,856; according to calculations by Harvard University’s Joint Center for Housing Studies, an affordable home for a median-income household would be $380,000.

But a shifting understanding of what constitutes “affordability” is only part of the problem. Does the simple fact of building more housing, even luxury housing, help alleviate the housing crisis in our most expensive cities?

Annie Schlechter; courtesy Toll Brothers City Living

The Sutton in New York, which includes subsidized “middle-income” apartments built as part of a controversial zoning program

The Shortcomings of Filtering

In an influential 2014 paper published in the American Economic Review, economist and Syracuse professor Stuart Rosenthal examined the process of filtering, by which yesteryears’ high-end homes become today’s lower- and middle-income homes. As wealthy people trade in their older expensive homes for new expensive homes, the theory goes, the older ones filter to less affluent residents. Filtering is the process by which the market, rather than government subsidies, provides renters and buyers with less expensive housing.

For years, Rosenthal wrote, economists simply assumed—without studying the phenomenon—that this filtering process happened. Examining housing data from 1985 to 2011, Rosenthal confirmed that filtering does indeed occur, and that it can be a reliable source of lower-income housing. But that discovery came with an important caveat. “Filtering is less pronounced in areas subject to high rates of house price appreciation,” he wrote. In other words, in the most heated housing markets—the markets that today are seeing the greatest numbers of new luxury condos—filtering is less reliable as a means of generating lower-income housing.

Evan Joseph Images; courtesy Toll Brothers City Living

The Sutton

Evan Joseph Images; courtesy Toll Brothers City Living

The Sutton

Jonathan Spader, a senior research associate at the Joint Center for Housing Studies, explains why. “At the same time that units might be filtering down, there are pressures between regions,” he said, referring to the impact of people moving to a city for new jobs. Particularly in high-demand places like New York, new expensive condos coming online may only decrease prices slightly, if at all, before newly arrived groups of affluent professionals move in. Units that, in theory, could filter to lower-income residents often don’t because someone with greater resources takes them.

Spader said it’s difficult to measure these regional pressures. There’s also evidence that filtering may only slow the growth of rental and sale prices and not decrease them. For these reasons, he says, cities will only solve—or at least lessen—their affordability crises by building new market-rate housing and by using government programs like vouchers, inclusionary zoning, and public housing. “You have to do both,” Spader said. “Adding new units has to be part of the response, but adding new market-rate units at the high-end, particularly in high pressure cities, may not alleviate pressures further down.”

Annie Schlechter; courtesy Toll Brothers City Living

The Sutton

Oddly enough, another Toll Brothers development illustrates the complexities of building truly affordable housing. The Sutton, on the Upper East Side, takes advantage of a controversial inclusionary zoning program in the city, 421a. Toll Brothers built 23 subsidized “middle-income” apartments, priced between $330,000 to $450,000, in exchange for a 14-year tax abatement on its 108 market-rate units, priced between $1 million and $8 million. Many housing advocates and experts have criticized the 421a program for waiving too much tax money: The city’s Independent Budget Office estimates that, over the next decade, 421a will cost New York $8.4 billion in property taxes. All for a program that critics contend will only make a tiny dent in the housing crisis. Indeed, Toll Brothers received 1,243 applications for its 23 subsidized units. Creating an affordable luxury brand is easy. Building, and maintaining, actual affordable housing is not.