Mayor Joe Riley is strolling through Charleston’s Waterfront Park, a leafy, 12-acre oasis where this 345-year-old city meets the dappled Cooper River. He stops suddenly, crouches slightly, and gestures ahead. “You see, right there!” he says in a loud whisper. “Someone’s got their feet up on the wall.”

It’s true: a young man in jeans sits on a park bench with his sneakered feet propped on a low retaining wall as he scrolls through his smartphone. It’s hardly the sort of thing that would merit notice among other park strollers. But for an urbanist like Riley, this is a sign that the park is working as intended, a clue that the city is on the right track. “Isn’t that great?!” he says.

The retaining-wall-as-footrest helps illustrate Riley’s close attention to—some might even say obsession with—the minutest details of city life. Prior to the 1990 opening of the park, designed by Sasaki Associates with Edward Pinckney Associates, Riley immersed himself deeply in the planning. He wanted benches deeply set enough for comfortable slouching (he instructed they be made 25 percent larger than the city’s previous benches), and urged that they be situated close enough to the retaining walls that people could sit with their feet up. He also had opinions about the height of those low walls: he concluded that 14 inches was optimal, high enough to offer an inviting challenge to toddlers, yet low enough not to injure those who fell. (“We studied that,” he says. “We wanted a place that once they got here, a parent could let the child’s hand go.”)

And then there was the gravel lining the park’s broad pathways. Riley instructed designers to send 40 gravel samples, making sure the size was right (“You want it so that you can walk in high heels”) and the color appropriate. “Charleston’s palette is this,” he said, nodding to the brick streetscape up the block, “so we made sure it had something called Baldwin Red in it.”

Waterfront Park

In December, Mayor Joe—as he seems to be universally called here—will leave office. Most residents have never known a Charleston without him: He was elected in 1975, and has held office ever since. (He’s now 72 years old.) By some accounts, he’s the longest-serving mayor presiding over an American city today. But by virtually every account, he’s been the key mover in shaping the architectural legacy of this small city (population 133,579).

Riley has long held that the public realm—parks, city buildings, and even the exteriors of private buildings—should always be artfully designed and built with quality materials. All kinds of citizens—wealthy, poor, black, white—will be attracted to these spaces and will be inspired to take ownership of them. And that in turn creates the bedrock of democracy. “Often architecture is thought elitist, that you’ve got to be schooled or have a special interest,” Riley says. “But not long after I was elected, I’d see visitors in town. They looked like they were retired blue-collar workers, and you’d see them admiring buildings. Beauty has no economic litmus test. It’s a basic human need and instinct.”

“It’s not a fetish, it really isn’t,” Riley says of his penchant for detail. It’s just that when the pieces fit together perfectly, he says, you build something bigger.

Which raises the question: Can that something bigger in Charleston survive Riley’s departure?

ADC Engineering

Charleston's 1804 City Hall, which was restored during Riley's tenure

Joe Riley is slightly built and soft-spoken with a thatch of gray hair. His owlish glasses seem appropriate for someone who wields intelligence and wryness rather than bluster as tools of persuasion. His perch in the city council chamber is a low platform facing the councilors, as if he were a college teacher in front of students. In his spacious upper-floor office, his desk faces a dozen chairs arrayed in two rows, like a repertory actor hosting a solo show in a small theater. His outsized ears appear to advertise the fact that he’s a good listener.

When Riley assumed his seat in 1975 it was at a juncture of opportunity and challenge. The opportunity came with a new system of voting for city councilors, put in effect just before his election, which led to the most black representatives on the council since Reconstruction. He vowed that his office would usher in a new era of openness and broader public involvement across the races, and bring to a close a time when major Charleston decisions involved furtive backroom deals.

Courtesy South Carolina Arts Commission

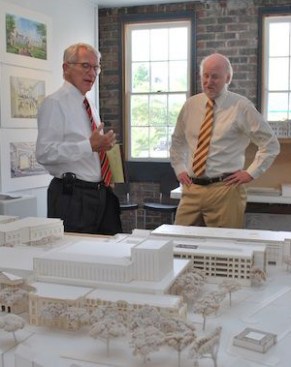

Mayor Riley (left) and Rocco Landesman, the former chairman of the National Endowment of the Arts, in front of a model for the recently completed Gaillard Center

The challenge he faced was more systemic and national in scope. At the time, America’s cities were still on a doggedly downward trajectory. Urban decay, fiscal crises, white flight, and racial strife had hollowed out urban cores. Downtowns were floundering, and many were ill-advisedly struggling for relevance by shoe-horning in suburban amenities—like high-speed arterials, strip malls, and acres of surface parking. Charleston was not immune.

Riley, a fifth-generation Charlestonian, was born here in 1943. He attended the Citadel and the University of South Carolina School of Law, became an active member of the Democratic party, and first tried his hand in politics in 1968, when he won a seat at the South Carolina House of Representatives. He served for six years before he became “the boy mayor,” as the local paper called him when he was elected.

Three years after taking office, Riley was invited to travel to Europe on a study trip sponsored by the German Marshall Fund of the United States. His group toured eight cities in Germany and England, studying what worked and what didn’t in the civic landscape. “I didn’t know what I was looking for until the end of the trip,” Riley says, “and then I realized I was seeing cities where the public realm was accorded the highest priority, and that the citizens revered that.

“Every city I went to I studied it—how it looked, how it worked. I read Jane Jacobs. Holly Whyte became a dear friend.”

A rendering of the International African American Museum by Pei Cobb Freed & Partners and Moody Nolan, a Riley-backed project proposed for the Charleston waterfront

Soon after, he had the opportunity to employ what he’d learned. In the mid-1980s, on five blighted blocks in Charleston’s historic downtown, developers proposed building a boxy, 14-story hotel with enclosed commercial complex, a 700-car parking garage, and exhibition space with its windowless exterior walls fronting an important street. Charleston preservationists rebelled; Riley backed them, insisting the project be reconfigured at a scale more suitable to the city and reorient itself toward foot traffic on the street. “That was brutally difficult and tremendously controversial,” Riley says. “But it was a key moment in the city’s history.”

The initial proposal was scrapped. The prominent developer A. Alfred Taubman stepped in and acceded to the mayor’s requests. The $75 million project, called Charleston Place and designed by John Carl Warnecke, had an eight-story tower, which was discretely set back behind four-story buildings with retail fronting the streets, some featuring façades salvaged from 19th-century buildings. An interior passageway connected two major avenues, weaving the project into the urban fabric.

The 1986 opening of Charleston Place

Riley didn’t ignore the city’s struggling areas either. On a driving tour of the city, Robert Behre, an architecture columnist for Charleston’s Post and Courier since 1996, slows as he passes one of many scattered public housing projects. Some were designed to look like traditional Charleston singles, narrow and tall; others were inappropriate brick ranchers built in an earlier era that were updated with Craftsman-style porches to better meld with the surrounding housing stock. “Nobody really recognizes them because they blend in so well to the city,” Behre says. ”But they’re so great because they don’t stand out.”

Other projects in Charleston that benefited from Riley’s oversight: a series of municipal parking garages that look nothing like parking garages (for one, he insisted on a stucco exterior and louvers); a sensitive rehabilitation of the 1804 City Hall; and the conversion of a former brick bus shed into a visitor information center. “We created a review committee for anything the city did,” Riley says. “This meant affordable housing, parking structures, any fire station, any park, anything the city built—including what the bathroom tiles looked like.”

ADC Engineering

Charleston's City Hall

For other projects, Riley constantly prodded architects and developers to learn the city’s vocabulary and grammar before submitting designs—“the rules of the public realm and the rules of human scale and the rules of caring about beauty,” as Riley puts it. Those who did so tended to have an easier time with the Board of Architectural Review (BAR), which has overseen much of the peninsula’s development since 1931, and to which Riley appoints members. Those who ignore this advice often find they have higher hurdles to jump. Steve Ramos, AIA, an architect in LS3P’s Charleston office, says he’s encouraged clients to scrap their preference for beige or yellow brick before review, since it’s well known the mayor considers this inappropriate. (The preferred color? Something locally known as “Riley red.”)

Riley often attends meetings of the BAR, but isn’t there to intimidate, local architects say. “What he tends to do, is that he’ll speak and then he’ll leave,” says Jennifer Charzewski, AIA, president of AIA Charleston. “He won’t stay around. I assume that’s so people can feel free to speak however they’d like after him. He doesn’t strong-arm the room.”

As such, the mayor doesn’t so much occupy the bully pulpit as the learned professor’s lectern. “People who build in this city know you’re interested,” he says. “The citizens know you’re interested. Your staff knows you’re interested.”

And people want to please the professor. Riley tells a story of stopping by a new plumbing supply warehouse out on the urban fringe. “You like my fence out there?” the owner asked Riley when he recognized him. Riley said he did. The owner replied, “Good. I wanted to build something you liked.”

David M. Schwarz Architects

Gaillard Center

If Charleston Place marked the effective beginning of Riley’s tenure, the massive rebuild of the Gaillard Center marks the end. The $142 million project, with David M. Schwarz Architects as design architect and Earl Swensson Associates as architect of record, is a grandly Neoclassical pile, unstinting in its use of limestone and columns, which essentially replaces a more modest performance hall that looked a bit like a midcentury high school. The Gaillard, which opens in October with a gala concert featuring Yo-Yo Ma, features an 1,800-seat performance hall, 16,000 square feet of meeting and exhibition space, a handful of municipal offices, and a triumphal entry plaza.

The mayor, naturally, visited the center every week or two while under construction to offer advice. (“They used Indiana granite. I didn’t think we should get variegated, but we got variegated from a nice bed.”) He views it as a lasting landmark. “It’s going to be beautiful, cherished and loved 100 years from now,” Riley told The New York Times.

David M. Schwarz Architects

Gaillard Center

Yet in some ways, the Gaillard is out of step with Charleston—in a city without icons, it appears to be straining for iconhood. “It’s Versailles,” says Whitney Powers, AIA, an architect with Studio A Architecture and an alternate on the BAR. “It’s completely ill-conceived. It doesn’t matter if it was old looking or new looking. The bottom line is, it was too expensive. Period.”

Jennifer Charzewski lets out a small sigh at the mention of the Gaillard. “I think there’s a sense among a lot of the architects that it’s a missed opportunity,” she says. “It could have been our Sydney Opera House.” And she worries it may create an untenable stylistic template. “The biggest fear I personally have is that the Gaillard Center will set a model that Neoclassical is the appropriate solution as a style,” she says. “But other projects won’t be able to match its level of quality.”

Indeed, questions of style have infused some recent architectural debates in Charleston. Clemson University this past summer withdrew its plans to build a new city architecture center in the face of neighborhood opposition. The three-story, 30,000-square-foot building—the Spaulding Paolozzi Center—had been designed by Brad Cloepfil, AIA, founding principal of Allied Works Architecture, and was to rise on a prominent intersection several blocks from the historic downtown. With its flat roof and perforated concrete screen, it was, as Powers wrote in a piece in support of the building, “like an exotic, interesting guest at one of Charleston’s poshest parties.”

Perhaps too exotic. Neighborhood groups hated that it didn’t look like Charleston. Clemson eventually withdrew the plan. Ray Huff, director of Clemson’s Charleston program, said the building sought to address Charleston-specific challenges—unrelenting sun, potential for floods and hurricanes—but never sought to mimic the city’s style. “This was not going to be a background building,” he says. “It was going to be an iconic civic building—of extreme high quality, durable, and yet respond to the issues of Charleston.”

Brad Cloepfil's unbuilt Spaulding Paolozzi Center

Charzewski, who supported the proposed structure, says that the debate reflected disagreement about where architectural experimentation is condoned, and where it’s not. “Everyone agrees that the historic core should be left alone,” she says. “But nobody can agree on the boundary or where the gray zone is.” The Clemson building fell into that amorphous area. (Riley remained neutral throughout the Clemson debate, but said afterwards of the university’s withdrawal that it was “a good decision. We watched the phases of design development, and it just got more harsh in its design. So much so that it just didn’t work there.”)

Riley is clearly enamored of traditional 18th- and 19th-century Charleston design, but local architects say he’s open to modern buildings when and where appropriate, such as when he championed the South Carolina Aquarium, designed in 2000 by Eskew+ Architects (now Eskew+Dumez+Ripple) with the late firm Clark and Menefee Architects and situated on a reclaimed cargo wharf outside downtown. “He’s a pragmatist,” Huff says. “He’s not someone resistant to change, but he has to feel it’s the right thing for the city. I think that what Joe looks for mostly is quality.”

Huff adds that Riley’s legacy will doubtless include that insistence on top-notch materials and techniques in pubic structures. (“When people complain about cost, I ask, ‘How many people know what the Spanish Steps in Rome cost?’ ” Riley says. “We don’t want to waste any money, but don’t be embarrassed, don’t be defensive.”) Huff also credits the mayor for “having the vision to recognize what is truly important—the public space and the scale of the street—and for creating and revitalizing institutions that oversee this, such as the planning department (which didn’t exist when he took office) and the Charleston Civic Design Center.

Timothy Hursley

South Carolina Aquarium

“What’s languished,” says architecture columnist Robert Behre, “has been the 20th-century suburbs. … What moves do we make in the suburbs to make them more appealing, to make them more viable and walkable?”

Powers says that the focus on urban aesthetics has overshadowed mass transit and other things that would enhance Charleston’s livability. “I would say we’ve been in a city beautification project for a long time,” she says, adding that relentless focus has “been how the city has been perceived rather than as an active environment—a place where people live.”

What direction will Riley’s successor take the city? Design wasn’t at the forefront of the political debate among the candidates. But one thing is certain: The new mayor (the election on Nov. 3 resulted in a run off between Leon Stavrinakis and John Tecklenburg) is not likely to be as attentive to the details of city life.

Earlier this year, Riley invited New Urbanist architect and planner Andres Duany, FAIA, with whom he has had a long working relationship and shared vision of urban life, to make recommendations for improving the city’s oversight of planning and design, with an aim of encouraging excellence in new buildings. (Duany’s report was released in late September.) “He talked a lot about the Charleston Brand,” says Ramos. That brand is not the city’s cuisine or its beaches, Duany said in several meetings both public and private, but its built environment—the distinctive architectural style, of course, but also how the homes evolved to adapt to narrow lots and a challenging coastal environment of heat and humidity. Architects should find ways to embrace and modernize that brand. As Duany put it in a meeting with local architects, “Why are we importing when we should be exporting?”

Riley says when he thanked Duany for being a great teacher, the architect responded that the mayor already had had the best teacher: “Your city. Your city and its rules that it has developed.”

If that’s the case, the city’s star pupil is graduating and moving on. He’s planning to do some consulting on urban issues, work with the Citadel and the College of Charleston’s Riley Center for Livable Communities, and generally remain active in what he calls “his life’s work”—improving and advancing cities everywhere. Yet his “best teacher” will remain, instructing the next mayor and Charleston’s citizens on what Riley summarized during his walk through Waterfront Park as “good rhythm, order, respect.”

“Have there been instances where Joe has been too hands on? No doubt about it,” says Ray Huff. “But at least I knew where he stood. And I think he’ll be remembered beyond Charleston’s history as a person who really got it. He knew how to make the city—not many people can say that.”

In his 1975 inaugural speech, Riley told the assembled crowd that as mayor he hoped to create “unwritten memorials … graven not so much on stone as in the hearts of people.”

By most accounts, he’s managed to create both.